“….To authors on works on hunting, [men] such as Gaston III, compte de Foix (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaston_III%2C_Count_of_Foix) and Edward, Duke of York (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward%2C_2nd_Duke_of_York), hunting was not just a sport or pastime, it was the essence of life itself….”

So writes Richard Almond in the Introduction to his book Medieval Hunting. And as you read this work, or others on the subject, you soon realise how very true a statement it is. So important were hawks and falcons that they could be worth more than gold!

Hunting with birds of prey was probably brought to Europe around AD 400 when the eastern Huns (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huns) and Alans (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alans) invaded. Whether that is so or not, it’s a fact that kings and princes have indulged in hawking and falconry for a l-o-n-g time.

The Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194-1250), King of Sicily, Germany, and the Roman Empire, had a falcon that was “….worth more to him than a city….” He was also the author of “…. what is now widely accepted as the first comprehensive book of falconry, the De arte venandi cum avibus (‘The Art of Hunting with Birds’). The treaty took him over thirty years to complete and is considered one of the first scientific works on birds’ anatomy and a founding book of ornithology….”

Harold Godwinson (c. 1022 –1066) enjoyed hawking too, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Godwinson and is depicted enjoying the sport in the Bayeux Tapestry. What a pity he didn’t fly his biggest, meanest bird at William the Bastard! We might have had a better outcome in 1066.

King Conrad the Younger (1252-1268 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conradin) was King of Jerusalem, Sicily and Duke of Swabia, and only sixteen when he fell into the wrong hands and was beheaded. But in his short life he’d enjoyed hawking, and below is a famous illustration of him indulging in the sport.

Codex Manesse (Folio 7r), c. 1304

Falcons were sometimes peace offerings too. “….In 1276, the king of Norway sent eight grey and three white gyrfalcons to Edward I as a sign of peace. A trained peregrine was the falconer’s most treasured possession and one of the merchants’ most costly trade goods….”

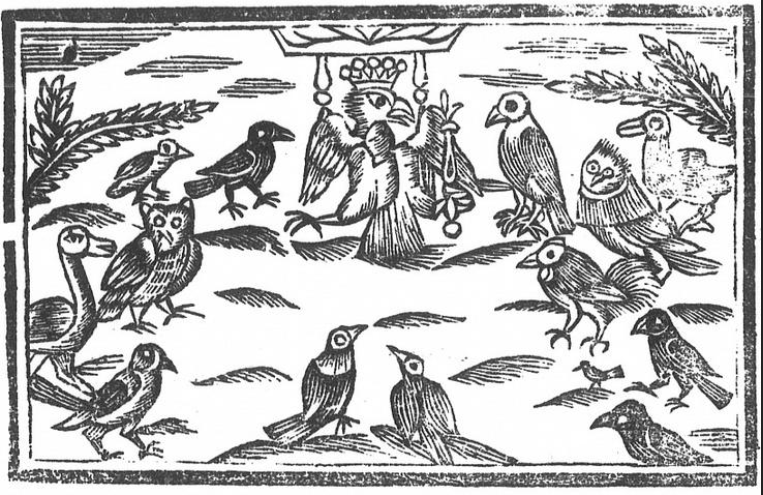

If you go to this link https://www.medievalists.net/2016/03/falconry-birds-and-lovebirds/, you’ll find an article about the connection (in the medieval mindset) between hawking and love. Even Chaucer was in on the theme with his Parlement of Foules, in which the bird argue over mates. (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parlement_of_Foules)

Falcons accompanied their masters over the Channel during the Hundred Year’s War. They were there at the great battles like Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt (the latter being Henry V, of course, not Edward III). According to Froissart, on invading France Edward III took “….thirty falconers on horseback, who had charge of his hawks, and every day he either hunted, or went to the river for the purpose of hawking, as his fancy inclined him….” And when Edward III had been on the throne for eight years, the King of Scotland “….sent him a falcon gentle as a present, which he not only most graciously received, but rewarded the falconer who brought it with the donation of forty shillings; a proof how highly the bird was valued….” (Both latter quotes from https://sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/spe/spe06.htm)

Edward’s grandson, Richard II enjoyed all forms of hunting, and built the Royal Mews at Charing Cross in London. The office created then, Master of the Mews, still exists today.

The Boke of St Albans (15th century) contains a celebrated list of who should or should not be permitted to have which bird of prey. Here is one version of it:-

The eagle, the vulture, and the merloun, for an emperor.

The ger-faulcon, and the tercel of the ger-faulcon, for a king.

The faulcon gentle, and the tercel gentle, for a prince.

The faulcon of the rock, for a duke.

The faulcon peregrine, for an earl.

The bastard, for a baron.

The sacre, and the sacret, for a knight.

The laner, and the laneret, for an esquire.

The marlyon, for a lady.

The hobby, for a young man.

The gos-hawk, for a yeoman.

The tercel, for a poor man.

The sparrow-hawk, for a priest.

The musket, for a holy water clerk.

The kesterel, for a knave or servant.

The above list is well known and is, unfortunately, taken seriously. But according to The Hound and the Hawk by John Commins: “…To a working falconer, much of this list would appear as pretty fair nonsense….the author of ‘The Boke of St Albans’ would have been surprised by the credulity with which its now hackneyed allocation of species continues to be accepted. It is partly a piece of fun….”

Merlins are the smallest of the birds of prey, and the St Albans list has it that they are for ladies. Well, they definitely were not just for ladies. Pero López de Ayala, 1332-1407, described in his Libre de la caça de les aves that Prince Philip, the fourth and youngest son of the French king, John II (John the Good), had once told him proudly that his merlin (probably a hen bird, for they were larger and stronger than the male) had captured upward of 200 partridges in a single winter.

At the Battle of Poitiers (19 September 1356) Philip, at the age of only 14, defended his father so fiercely he earned his famous nickname, Philip the Bold. He and and his father were captured by Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, (known to posterity as the Black Prince) and brought back to England,where , although prisoners of war, they were treated with regal hospitality.

In his book Philip the Bold, Richard Vaughan tells how Philip played chess with the Prince of Wales and “…was instructed in the intricate art of falconry by the French royal chaplain, Gace de la Buigne, who had voluntarily followed his master into captivity…” So Philip the Bold certainly knew about birds of prey, and thought highly of the little merlin he’d once had. Therefore merlins were definitely not for ladies only. They were considered suitable for the son of the King of France!

Another story about Philip the Bold and birds of prey is this: “….Falcons were highly valued. During a crusade in the late fourteenth century, the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid captured the son [John of Nevers] of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. 200,000 gold ducats were offered for ransom to recover the man and turned down. What Beyazid wanted (and was given) was something more precious: twelve white gyrfalcons….” (from https://tinyurl.com/5893s4p4 and see also https://www.medievalchronicles.com/medieval-life/medieval-games/falconry/)

So all in all, Philip the Bold was definitely keen on hawking. And hunting too, of course, and it’s interesting that Gaston Phoebus’s immensely important book on medieval hunting was dedicated to Philip. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Livre_de_chasse)

Sometimes sources unwittingly cause amusement. For instance: “….The Stuarts were particularly fond of the sport of falconry, with Henry VIII being considered by some as the most important falcon advocate since Frederick II….”

Surely not even the Stuarts would want to claim Henry VIII! He’s ALL Tudor and they can keep him. The source of this little giggle is the article https://tinyurl.com/y7xkau63 by Medieval Life.

By little_miss_sunnydale, live/staticflickr.com

For a later period, the Regency, try https://regency-explorer.net/falconry-in-the-romantic-age/

More about falconry: https://thefalconryschool.com/news/the-history-of-falconry-in-britain-part-one/ and https://thefalconryschool.com/news/the-history-of-falconry-in-britain-part-two/. To read about the various different birds of prey, try https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bird_of_prey)

There are, of course, countless sites about medieval hawking. Once you’ve started looking, you’ll soon be overwhelmed! ☺️

by viscountessw

Leave a comment