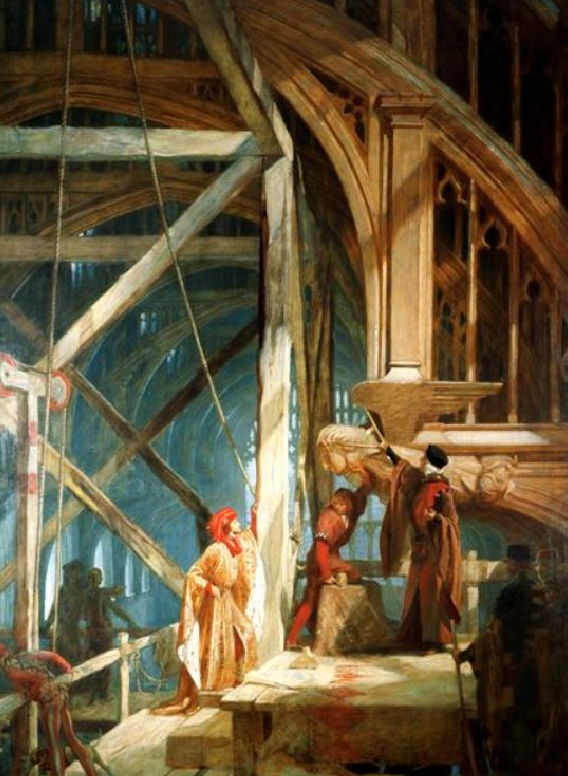

We all take for granted that the hammerbeam roof of Westminster Hall (see https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/westminsterhall/architecture/the-hammer-beam-roof-/) is a true masterpiece of medieval workmanship and innovation. Many of us know that the transformation of the (then) huge building was at the instigation of Richard II. But how many of us know of a painting that captures a fleeting moment when Richard and his master carpenter, Hugh Herland, (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Herland) are inspecting the progress of the new roof? The great master mason Henry Yevele (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Yevele) was responsible for transforming the entire hall. What an astounding metamorphosis it must have been after the austere Norman presence of the original.

Apparently in 1921 the artist Salisbury seized his opportunity when work was done to repair and reinforce the roof. The artist was able to place himself on the scaffolding exactly where he envisaged the view depicted in his finished painting. Hence the exceedingly accurate angles and detail of the roof and appreciation of the size of the hammerbeam angel. Speaking of which, I do hope the poor chap between Richard and Herland isn’t having to hold up the angel entirely on his own, with one hand! ☺️

The finished canvas is large at 8 feet 7 inches high by 6 feet 4 inches wide, and I’d love to see it “in the flesh” so to speak, but haven’t managed it yet.

It happens to be one of my favourite paintings of Richard II. Caught in a shaft of sunlight, he’s dazzling in a long gown of cloth-of-gold and ermine, and an elaborate red chaperon hat with what seem to be liripipes or scarves over both shoulders. And he’s leaning forward with interest as Master Herland (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Herland) explains some finer point of other. I could almost be there too, observing from the shadows. Mind you, making his way up wearing all that royal splendour while maintaining his dignity can’t have been easy. But if anyone could manage it, I’d say the elegant Richard most certainly could. And once he’s there, how impressively regal he is, even in such an informal setting.

To me the painting says everything about Richard. Yes, he was vain, but he had the looks, height and bearing to appear to best advantage in the array of magnificent royal clothes at his disposal. And he had a sense of style second to none. But he’d been king since he was a child, overruled, bullied and stifled by his uncles and the great magnates, so it’s small wonder he emerged as damaged goods. I’ve used the phrase “damaged goods” to describe him before, but in my opinion it fits him perfectly. He tried according to his conscience, and he was never the murderous, thieving tyrant that has come down to us through the centuries. That distinction goes to his first cousin, Henry of Bolingbroke, who stole the kingdom, the crown and Richard’s life. In that order.

In true British style, I’m all for the underdog, and to me it’s Richard II. He struggled to wrest the right to rule from those who wanted it for themselves, and if he floundered a little afterward, well, he wasn’t perfect. None of us are. I really do like the image of him in this modern painting, because in this brief moment he is truly himself. There he is, watching and listening attentively. It’s a great shame that circumstances suffocated the real Richard. But for that the Renaissance would certainly have flourished in England far sooner than it actually did.

Last year I considered another intriguing modern painting featuring Richard II, this time by Norman Wilkinson (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norman_Wilkinson_(artist)). I’m sorry it isn’t sharply defined in the image below, but it’s the best I can find/do. You can read my article about it here https://murreyandblue.co.uk/2024/08/03/a-very-telling-portrait-of-richard-ii/ The artist has caught the rather haunted look that I believe Richard would have had when he was off-guard. But of course that look can also be interpreted as scheming and sly, depending upon your opinion of this enigmatic king..

Richard was a very complicated man, a fish out of the water for his time, preferring the arts to bloody conflict, but peace didn’t do for his warlike aristocracy. As I’ve said above, he tried his best but wasn’t perfect, and he certainly didn’t deserve to die at the greedy, self-serving hands of his Lancastrian cousin.

Leave a comment