What if, what if….those words are surely the motto of every fiction writer that ever was.

As such a writer myself, I’m quite accustomed to seeking plausible but hopefully exciting and entertaining answers to known puzzles. By this I mean answers that could explain “what really happened”. Complete impossibilities have to be thrown out. For instance, a plot that has Richard III being over the border fighting Scots on the same day as his coronation in Westminster would be too ridiculous to take seriously. He’d have a job to do both in one day even now, unless he could move at warp speed!

As an example of a possibility, how about transforming into passionate lovers two real figures from history who may not have actually fancied each other at all? All the better if there’s a strong possibility that the persons in question could have been or were in the same place at the same time, to enable an affair. It always has to be possible, not impossible. There must be a decent plot too. Just writing a string of steamy scenes is NOT enough. Believe me, it’s not as simple to write to this formula as non-writers like to scoff in order to make themselves feel superior.

Books with covers like the one above are all too often dismissed as silly bodice rippers etc. Women’s stuff. Rubbish. Sometimes the writing inside these covers deserves to be mocked (never mine, of course, because I’m always brilliant! 🙄) but all too often the condemnation does a grave disservice to those authors who just might have happened upon something new that merits closer consideration.(*)

So I like to find a writer who uses imagined but feasible situations with actual people and conjures them into a good story. The author in this case is Libby/Elizabeth Ashworth, who in March 2013 wrote the following article on her website: Richard III, his mistress, and his illegitimate children – Libby Ashworth – author. She wrote it to draw attention to her book By Loyalty Bound, which I haven’t read and am therefore not reviewing or criticising in any way whatsoever. I simply found what she had to say about her plot interesting and worthy of more scrutiny. So what I’m going to write now is based only on the premise of the plot, not on what actually appears in the book.

We always believe that Richard’s great love was his queen, Anne Neville (younger daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, the “Kingmaker”), and I certainly concur in this. There’s no suggestion of him fathering any illegitimate children after his marriage. But what if, before he and Anne Neville were an item, there had been someone else who’d won his heart? I’m not belittling the love he undoubtedly felt for Anne Neville, but was she his first and only love? He had a baseborn son and daughter. Were they merely the result of casual one-night stands before his marriage? Or of something much deeper?

Women like Katherine Haute and the nurse Alice Burgh have been posited as his possible bachelorhood mistresses. These two are selected mainly because of speculation concerning the annuities he granted to them in 1474 and 1477 (giving only vague reasons for his generosity). The annuities wwre not given immediately on the birth of any child, because these dates are after his marriage to Anne Neville. Anyway, Alice’s annuity was far larger than Katherine’s, so perhaps, as Ms Ashworth points out, this rather puts her into perspective. And Alice too, come to that. I don’t have a date for the birth of Richard’s daughter Katherine, but I have seen circa 1468 given for his son, John of Gloucester. For both see https://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/plantagenet_86.html.

In 1475 George, Duke of Clarence, the middle brother between Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester, would appoint Alice as the nurse of his son and heir. So she was a nurse, not a royal mistress in nurse’s clothing. But there’s no proof of anything. It’s all smoke and mirrors.

Ms Ashworth drops a new name into the brew, and “….although this is also based on speculation as the other names are, there is some circumstantial evidence that she may have been his mistress….” Ms Ashworth’s lady just could, possibly, have been a love of Richard III when he was still Richard, Duke of Gloucester and they were both in their teens. She might also be the mother of one or both of his baseborn children. Then again, of course, she might not, but if at any point Richard and this lady were together, Ms Ashworth is prompted to wonder if it’s “….possible that these two young people were attracted to one another?….”

The lady in question is Anne Harrington, and I had heard of her before but not in this context. She was an important element of the famous decade-long feud between the two prominent Lancashire families of Harrington and Stanley, the stirrings of which began in 1460/1. But she and Richard could have been together where they needed to be at a particular moment in early 1470.

And do not forget that what follows now took place against a background of royal musical chairs. It was the Wars of the Roses, and the throne of England was swapped a number of times. Henry VI, Edward IV, Henry VI, Edward IV….Lancaster, York, Lancaster, York. Everything alternated in quick succession, but one great magnate straddled it all, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick—Warwick the “Kingmaker”, father of Anne Neville.

The Harrington-Stanley feud has been mentioned a number of times in this blog, as you can see from the links given below. The feud began when Yorkist Sir John Harrington of Hornby in north Lancashire died along with his father at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460. The 3rd Duke of York also perished at the battle, but on 4 March 1461 his eldest son, a brilliant and charismatic young warrior, became the first Yorkist king, Edward IV. Aided by the powerful Warwick, he drove the ineffectual Lancastrian Henry VI from the throne….for the first time.

The Harrington deaths at Wakefield meant that Sir John’s little daughters, Anne (probably five) and Elizabeth (four), were now the heirs. They became wards of the new Yorkist king. The influential Stanley family had coveted the Harringtons’ main residence, Hornby Castle, for quite some time, so Anne and Elizabeth were of immense interest to them.

These Stanleys were the Stanleys, the creatures of ill repute loathed by those of us who believe Richard III was a good king and innocent of the crimes of which history accuses him. At the outset of the feud the Harringtons and Stanleys were both supporters of the House of York. They were also kinsmen who shared a Harrington great-grandfather. The knightly Harringtons would remain Yorkists, but the baronial Thomas, Lord Stanley, was a master fence-sitter, dropping down on whichever side would most benefit him. His family’s only true loyalty was to itself.

It should also be noted here that Warwick and Lord Stanley were brothers-in-law. In October 1470, when Warwick changed allegiance and ousted Edward IV to reinstate the ineffectual Lancastrian Henry VI, Stanley would promptly jump over the fence to adjust his allegiance too.

Shifty is an adjective often applied to Stanley, and it’s very fitting because that’s what he was. He could shift very quickly, and his character was sly and shifty too. One has to wonder if the man’s own reflection dared trust him! He’d already shown his treacherous side several times, including in early 1460, when Richard encountered (or was ambushed by) Stanley’s men on the road in Cheshire, see here https://murreyandblue.org/2017/07/20/while-on-a-cheshire-road-richard-duke-of-gloucester-happened-upon-the-retainers-of-thomas-lord-stanley/. There was a skirmish and Stanley’s men were scattered. Stanley managed to whinge his way out of it, but now had reason to dislike and resent Richard.

Nevertheless, in November 1461 Edward IV granted the girls’ wardship and marriages to Stanley, who thus obtained “….the right to marry them to husbands of his choosing – men who would become owners of the Harrington lands….” If I understand correctly, Stanley would enjoy the profits of their estates while they were considered minors, but it was their marriages that would secure his permanent possession of their Harrington lordships. These lordships included Hornby Castle, which Lord Stanley had craved for so long. His power and influence was greatly enhanced by being the girls’ guardian, but would be far more impressive when he achieved their marriages.

Anne was the main heiress, and whoever became her husband would gain most, especially Hornby. But to get his hands on everything, Stanley had to both girls in his care physically. Edward IV had agreed that they would be handed into the keeping of his wife, Eleanor Neville, Warwick’s sister. But that wasn’t to happen.

This was because Edward IV’s grant to Stanley effectively disinherited the girls’ uncles, Sir James Harrington of Farleton in Cumbria and Brierley in South Yorkshire, and Sir Robert Harrington of Badsworth, in West Yorkshire. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Harrington_(Yorkist_knight) and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Harington,_3rd_Baron_Harington). With friends like Edward IV the loyal Harringtons didn’t need enemies, nor did they take it lying down. James considered himself to be the rightful heir because he was Sir John Harrington’s next brother, i.e. male heir, and he wasn’t about to hand his family’s inheritance over meekly to the Stanleys! And the girls were in his possession.

Given all the discord that was about to erupt, I imagine Edward often had cause to regret his decision. He showed favour to James and Robert in other ways because he wanted to keep them onside, but I doubt if they ever felt true personal loyalty to him again. To Richard, yes, that much is crystal clear. But Edward IV’s original grant to Lord Stanley had been an unwise move that opened a Pandora’s box with far-reaching and terrible consequences for Richard.

Anyway, on the king’s grant a heated dispute had broken out as to whether or not the Harrington estates passed in tail male, that is through the male line only (Harrington claim), or in fee simple, through male and female lines (Stanley claim). But the Harringtons were on a loser because the fact was that the girls had come into Edward IV’s care and he had awarded them to Stanley. Ill-judged maybe, but it was legal fact.

According to Ms Ashworth: “….In 1465, James Harrington was one of the men who captured Henry VI who had been hiding out in Lancashire. He was delivered to Edward IV who kept him captive in the Tower of London. I think that James Harrington may have hoped that this act of loyalty would make Edward look more favourably at his claim to Hornby, but although James was rewarded, the castle was not returned to him….”

So James continued to resist the king’s decision with all his might and by late 1466, he was still well and truly in physical (if not lawful) possession of Hornby and the girls. Stanley obtained permission to sue him in the courts, but it wasn’t until two years later, 1468, that the final, undeniable verdict went in Stanley’s favour.

As a consequence James and his brother Robert were, for a while, incarcerated in the Fleet Prison. But on release, still unchastened, they continued to hold on to Hornby and the girls against Stanley and were still hunkered down for the long haul. Please note that neither James nor Robert Harrington necessarily did the hunkering in person at Hornby, as will be explained. They simply filled their castle with their armed supporters, while they and their hostages were elsewhere.

The girls seem to have been more held against their will than nourished in Uncle James’s fond bosom. In pages 33/34 of his Stoke Field book, David Baldwin states that immediately before or just after Bosworth, probably at the instigation of Lord Stanley, the girls complained in law about their abduction and imprisonment. By then they were Stanley wives and therefore part of one of the most important northern baronial families. With knightly James they were probably tiresome nieces who were the root of a lot of strife. Heaven knows what sort of marriages he’d have bestowed upon them. Then again, he might have been fair. He had to have virtues if Richard accepted him as a close friend. But we’ll never know.

It’s necessary to put into context the ages of Anne Harrington and Richard in March 1470, when he was present at Hornby. There’s no help from the date of her parents’ marriage, because it isn’t known, so we’re left with differing sources. Some say Anne was born circa 1456, so from being five-ish in 1460 she would be around fourteen/fifteen in 1470. However, some sources say her birth year was circa 1459, but that would have made her only about one after Wakefield, and Elizabeth still a naught! That also means that in 1470, Anne would have been around eleven. Too young, surely? But the use of “circa” for both birth years gives leeway in either direction. I’m going with Anne being five in 1460, which means that in March 1470 she’d be at least fourteen, old enough for there to be sexual interest from a seventeen-year-old Richard. And vice versa, of course. Anne Neville was also around fourteen.

The medieval convention was that girls were considered old enough to consummate marriage at twelve, and boys old enough at fourteen, although this certainly wasn’t strictly adhered to, after all not all girls had reached puberty at twelve, and not all who had were considered developed enough to bear children. In general it seems that girls were about fifteen/sixteen before consummating marriage.

So while we today would consider Anne Harrington too young to be married at all, she wouldn’t have been considered so in her own day. But as a maiden heiress of a prominent Lancashire family she was definitely expected to go to her husband’s bed still a virgin! If she didn’t, woe betide her, for things were not as they are now. Mind you, if she fell by the wayside with someone as powerful as the king’s brother? What then?

There is another problem, and that is the sort of man Richard of Gloucester was. He’s known to have been pious and just, always honoured women and sought to improve their rights, and throughout this period he is believed to have been in love with Anne Neville. We know she was to be his wife and eventually his queen, but do we actually know when they first became an item? They’d grown up together at Middleham, Warwick’s Yorkshire stronghold and it’s thought that they were in love even as children….which surely means they still were when Richard was at Hornby Castle.

So was he really likely to have deflowered the virginal, spoken-for Anne Harrington? I have to doubt it. This would surely have been regarded as an immense insult and faux pas, to the Harringtons and the Stanleys, from whichever point of view one looks. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t….after all, he already had a illegitimate son born 1468, and was to have a daughter as well. We know they were his because he acknowledged them.

Such scruples didn’t trouble Richard’s brother Edward IV, of course. He was prepared to resort to any subterfuge to get ladies into his bed. Just think of Lady Eleanor Talbot and Elizabeth Woodville, and they’re just the ones of whom we know. The likes of “Jane Shore” (or whatever her actual name was) were not ladies. For Jane Shore see https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/jane-shore-0011174.

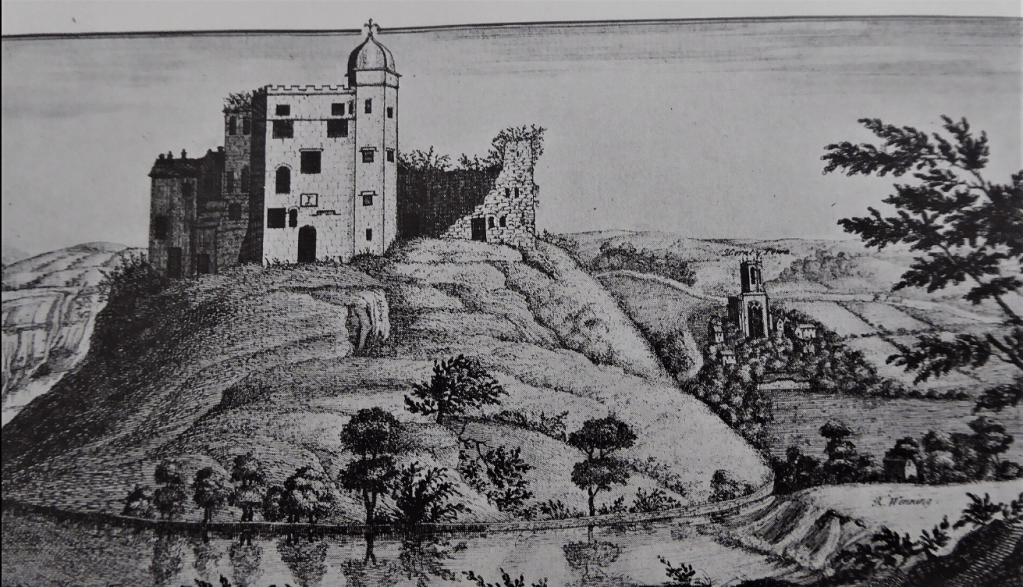

By March 1470 Lord Stanley had lost patience and set about teaching James Harrington a lesson by laying siege to Hornby. Edward IV sent Richard to Hornby to put the Stanleys in their place. This was after the skirmish in Cheshire, and Edward thought the Stanleys were becoming too big for their boots. To be frank, by then it was a little late to think of that when he’d played a large part in their expansion! At Hornby on 26 March 1470 Richard issued and signed a grant to an esquire, Reginald ap Gruffudd Vaughan, and this is what proves his presence at the castle on that day.

Richard’s friendship with James Harrington raises another aspect to the possible liaison between Anne Harrington and Richard of Gloucester when he was at Hornby. If the girls’ later complaint was true, and if they were there at the same time as Richard, they were opposed to James Harrington whereas Richard was James’s close friend. So would there have been more aggravation than anything else between Richard and Anne? If there was conflict, of course, a writer of fiction is presented with tempting opportunities for setting sparks flying.

Richard left Hornby by at least early April 1470 because he was with Edward IV nearly 300 miles away in Exeter on 15 April 1470. He was never to return to Hornby. At least, if he did, there doesn’t seem to be any record. Rebellion had broken out and Edward needed him. What with all the to-ing and fro-ing, invasions, rebellions, exiles and swapping of kings that now followed in quick succession, I’d be wandering from the point of this article if I went into detail. So I’ll only include points of relevance to my subject.

Richard and Edward IV fled into exile in the Low Countries from 3 October 1470, and when Henry VI was king again on 5 March 1471, Warwick sent a great cannon to Lord Stanley. Was Stanley’s reasoning that if he couldn’t have Hornby, neither could James Harrington? But even if he’d been using smaller cannon all along, by aiming a huge one at the castle, surely Stanley must have been certain that Anne and Elizabeth weren’t there. Using cannon at all was a risk, but to bombard Hornby with a monster weapon when the girls were inside would run the risk of killing them. He needed them alive to be married to members of his family.

To move on. Edward returned England within days of the cannon’s despatch. Warwick was killed at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Barnet), and Henry VI’s son (by then Anne Neville’s husband) died at Tewkesbury, less than a month later, 4 May. (See https://www.tewkesbury.org.uk/the-battle) This time Edward made sure of keeping his kingdom by doing away with Henry VI. Well, put it this way, if Edward wasn’t behind that unfortunate man’s convenient demise, the death was astonishingly serendipitous.

At last Edward IV was truly secure upon his throne….and one of the first things he did was order Stanley to disband his force and keep the peace. Had the great cannon ever been fired? If it had, Richard had certainly not been there, because it arrived at Hornby when he was still in exile. It’s often said that on 26 March 1470 Richard issued a warrant that dared Stanley to fire at the king’s brother, but what Richard issued that day was a grant to an esquire. So it seems the presence of the king’s brother at the besieged castle was simply to deter Stanley. If Richard had ever been on the receiving end of any Stanley cannon fire it had to be from any smaller weapons Stanley might have used throughout the siege. I don’t know where the “daring” aspect came from, unless it was Edward IV doing the daring by placing Richard there in the first place.

Stanley had been a veritable yo-yo throughout all the mayhem. When the wind finally blew the wrong way for the House of Lancaster….and Warwick was no more….our shifty northern lord clambered swiftly back up the fence and dropped down again on the Yorkist side. And he got away with it! That man led a charmed life! Loathe him as we will, we have to admire his nimbleness! But he bore a grudge against Richard that would one day surface to devastating effect at Bosworth.

The death of Anne’s husband at Tewkesbury freed her to marry Richard in the late spring/early summer of 1472, it’s thought in St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster. The actual date isn’t known. Richard is believed to have been an entirely faithful husband from then on.

Another marriage that took place in June 1472 was that of Lord Stanley. His wife, Warwick’s sister, had passed on and now he became the husband of Margaret Beaufort, mother of the future Henry VII. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Margaret_Beaufort.) It was an incredibly fortunate and important marriage, giving him influence throughout the land, not just in the north. And his wealth was a carrot to her. There had already been ominous Stanley clouds looming, but now there were to be even more. Especially for Richard.

By August 1473 James Harrington and his brother were still holed up at Hornby and Edward IV was still careful to show them favour, but now he had to use more heavy-handed means to winkle them out. He succeeded and the feud was ended—although I don’t know exactly when, except that it can’t have been instant because the girls’ marriages weren’t until 1475. But then, at long last, Lord Stanley could act upon his wardship rights and take possession of Hornby and the girls.

Anne—who surely had to be virgo intacta because I have to wonder if she could really play the part when she’d given birth—was married to his fifth son Edward (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Stanley,_1st_Baron_Monteagle) and Elizabeth to his nephew Sir John Stanley of Melling (https://www.geni.com/people/Sir-John-Stanley-Jr-of-Melling-Knight/6000000046241293826). Both marriages would have been consummated immediately, thus eliminating the risk of annulments leading to the Harringtons reclaiming everything….or anything at all!

During the feud both girls are often said to have been at Hornby, but is there actually any proof that either of them ever was? According to historian David Baldwin (pages 33/34 of his Stoke Field book), although the girls were in the hands of James Harrington when he seized Hornby Castle, they were moved “…contrary to their will in divers places….”

Was Hornby Castle one of these “divers” places? I hesitate to believe so because throughout the dispute, James Harrington apparently resided at his manors of Farleton in Cumbria and Brierley in West Yorkshire. So although he may have “seized” Hornby, he himself probably wasn’t there (nor would Robert have been, I imagine) and if the girls were there at the outset, they were moved around pretty quickly to keep them out of Stanley’s reach.

As yet I haven’t found a reference to where they actually were at any given time. But might there have been a point when Anne and Richard of Gloucester met at Hornby, and she was at least fourteen? There doesn’t seem to be anything that says this couldn’t be so, but even if they did meet it’s not evidence of an affair either. Nor does the fact that these two young people had reached a time in their lives when hormones are rather rampant. In truth they might not have liked each other at all, but what if they did fancy each other something rotten?

Now, here’s a possible glitch to Ms Ashworth’s theory. One site gives Anne Harrington’s date of death as 5 August 1481, which if true means she was in her twenties when she passed away, so I imagine she and Edward Stanley had shared their 1475 marriage bed for possibly half a dozen years. If she gave birth to any living children who died very young, or if she suffered miscarriages or stillbirths, I haven’t found any record. However, the fact is that Edward went on to have surviving offspring by his second wife and by an unknown woman, which makes me wonder if—maybe—Anne was barren, or at least couldn’t carry to full term.

There again it’s possible she and Edward were seldom together after the initial wedding night. This is all guesswork on my part, of course, but if she and Edward Stanley did share a marriage bed regularly and she didn’t give him a surviving child, she probably couldn’t have produced one for Richard of Gloucester either….and we know he fathered children.

James Harrington remained Richard’s close friend and supporter, and fought at his side at Bosworth, as did Robert Harrington. James may have perished in the field along with Richard, but Robert certainly survived to be attainted and then pardoned by Stanley’s stepson, Henry VII.

It appears that at the time of Bosworth Richard probably intended to “….re-open the debate about Hornby with a view to returning it to the Harringtons….” Being by then a grief-stricken widower who’d also lost his only legitimate child, Richard was probably more understanding than ever of the Harrington plight. But if this was his intention, it would have galvanised the Stanleys into action to kill him before they lost Hornby.

As far as I’m aware no whisper seems to have escaped about a liaison between Richard of Gloucester and Anne Harrington, except from Ms Ashworth. So let’s consider the, er, mechanics of it all. Richard could have met Anne Harrington in March 1470, but even if they’d had fallen into bed together immediately, she couldn’t have given birth until December 1470, earliest. By then Richard was exiled in the Low Countries, which meant that another pregnancy by him was impossible. So Anne Harrington might have borne him one child, and as John of Gloucester’s birth is generally given as 1468, then maybe Katherine was Anne Harrington’s child. The timing fits.

Well, I for one am prepared to give Anne Harrington some consideration. Why should I not? Find me one cast-iron reason to dismiss Ms Ashworth’s theory out of hand. Anne Harrington and Richard of Gloucester might well have been two young people thrust together at a time of strife and might well have experienced life-or-death emotions that would otherwise not have flared into being. It’s possible, not impossible, so Ms Ashworth is justified in creating a story based around Richard and Anne Harrington getting together.

Ladies and gentlemen, you must make up your own minds about Ms Ashworth’s plot. Etiquette before emotion? Or would he, at seventeen, be as prey to his teenage urges as most young men of that age still are today? And always will be, come to that. Might Richard’s feelings for Anne Harrington, and hers for him, have been fierce enough for them to break important rules? If those feelings ever existed in the first place, of course.

But what he felt for Anne Neville certainly did exist, so did he cheat on their love? Baseborn children are baseborn children and he’d been old enough to father them before marrying Anne in 1472, so if he and Anne Neville had been in love since childhood….well, do the maths.

One last point though, the above cover of Ms Ashworth’s book describes Anne Harrington as Richard III’s mistress. If she died on 5 August 1481, she could only ever have been the mistress of Richard, Duke of Gloucester. But that’s me being picky. A single reference to 1481 as the year of her death doesn’t mean it’s carved in stone.

And if you by any wild chance want to know my opinion of the notorious feud itself, it’s that the Harringtons were shafted by Edward IV and Henry VI, and then attainted by odious Stanley’s odious stepson, Henry VII ,for supporting Richard at Bosworth. Robert was eventually pardoned. Only Richard III stood up for the Harringtons, and this friendship and loyalty went toward his betrayal at Bosworth. Edward IV’s Pandora’s box had indeed resulted in far-reaching consequences for his youngest brother….

For a detailed history of Hornby and its castle, go to https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol8/pp191-201, although it doesn’t refer to the feud.

You can read more about the Stanleys and Harringtons here https://murreyandblue.org/2022/12/05/the-rise-of-the-stanley-family/, here https://murreyandblue.org/2021/01/30/the-harringtons-of-hornby-castle-and-the-stanleys/, here https://murreyandblue.org/2017/07/22/richard-the-stanleys-and-the-harringtons/ here The Murderous Stanleys of 15th-century Lancashire…. – murreyandblue and here: https://www.historyhit.com/why-did-thomas-stanley-betray-richard-iii-at-the-battle-of-bosworth/.

(*)As an example of a chance find that is possible I give my own discovery of something that might prove when exactly the remains of Edward II were brought to St Peter’s Abbey (now Gloucester Cathedral). It certainly wasn’t immediately after his apparent demise at Berkeley Castle in September 1327. My new circumstantial evidence supports the modern thinking that Edward survived Berkeley and died abroad many years later. Until then his resting place at Gloucester had been empty. After all, his son Edward III had taken the throne so the death-at-Berkeley story had to be believed….and the tomb considered to be occupied. When Edward II’s real time came his remains were brought home and interred secretly in their waiting resting place. And this in the full knowledge of his son. My discovery was to do with the precise timing of this return to England, and the presence at Berkeley of a very important English royal at a significant moment in the calendar. It may not mean anything at all, but the fiction writer in me can see so very much. It’s possible, not impossible! Read about it here: https://murreyandblue.org/2024/03/06/a-circumstantial-but-viable-clue-to-the-eventual-death-of-edward-ii/.

What if, what if….those words are surely the motto of every fiction writer that ever was.

Leave a reply to Could John of Gloucester have had children….? – murreyandblue Cancel reply