I have written articles on this blog about the disgraceful way many 14th-century knights abducted women and married them by force. These men’s prey were usually widows with attractive fortunes that could provide their callous bridegrooms with the comfortable later life said scoundrels hadn’t bothered to prepare for during their careers (often as soldiers).

Even women who’d retreated to the Church were unsafe from these predations, and there were some notorious cases. The king’s kinswomen were as much at risk as lowlier widows, and if the knight in question was an old soldier, the king himself and his son Edward of Woodstock (see Edward the Black Prince) actually condoned these offences. While at the same time considering their royal selves to be shining and heroic examples of chivalry, of course. Not in my book they weren’t!

Of course there were women who participated willingly in these ‘abductions’. By seeming to be whisked away against their will they escaped situations or surroundings they disliked or were confined. The sought-after result was to be with the lovers they’d been seeing sneakily all along. Elizabeth de Juliers wasn’t in this category. She wanted to marry her chosen bridegroom, and made herself free to do so by breaking her self-imposed vow of chastity. Nor was her husband-to-be an impoverished knight needing to lay hands upon her fortune. On the contrary, he was a wealthy man.

But in burrowing further into her story I was to come upon a mystery surrounding the man she took as her second husband. Was he or was he not a Founder Member of the Order of the Garter? Or was that his elder brother? Or was there just the one man all along? Or….maybe the bridegroom was even an imposter? The more I delved, the more anything seemed possible.

With Elizabeth de Juliers it was a pleasant change to happen upon a highborn widow who, as a very young widow had retreated to Waverley Abbey eight years earlier on the death of her 22-year-old husband, then suddenly changed her mind and cast off her vow in order to become a wife again. Today—Michaelmas Day, 29 September—in 1360, at Wingham church in Kent, she married a man not all that many people seemed to know she’d even met before.

Elizabeth was the youngest daughter of William V, Duke of Jülich (He had been Count of Jülich but was raised to duke in 1356/57. Please note too that in Edward, Prince of Wales, Barber, pages 33 and 34, in 1340 Juliers is referred to as Marquis of Juliers, and described as one of Edward III’s chief allies in Flanders.) Back to his youngest daughter. Elizabeth, was also the niece of the Hainaulter Queen Philippa of England and the widow of John, 3rd Earl of Kent (see here). So she was definitely way above the average bride likely to attract the average knightly rogue on the make.

Elizabeth is also known as Isabelle. The two forenames are separate now but were taken as one in the medieval period. And while on the subject of names, there are numerous spellings of d’Aubrichecourt, but unless quoting directly from a source I have stuck with just the one throughout.

Elizabeth’s age isn’t known but she may have been younger than her first husband, John of Kent, because there’s a suggestion she wasn’t of an age to consummate her marriage by the time John died in 1352. Virgin widow or not, she took a vow of chastity and retreated to prestigious Waverley Abbey, which wasn’t far from some of the important dower lands she received from her marriage. To see this suggestion of Elizabeth’s youthfulness see Anthony Goodman’s Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent, page 44.

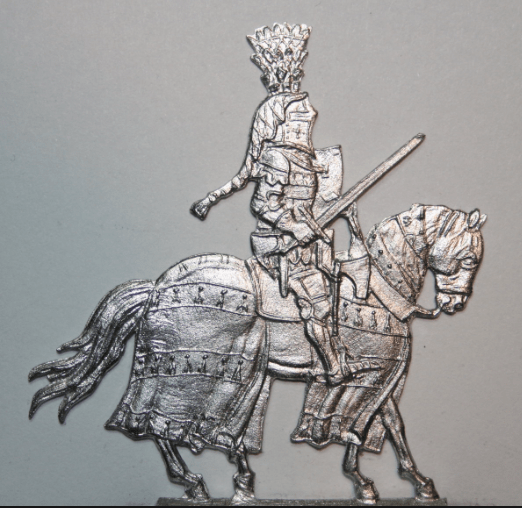

Her new bridegroom was the Hainaulter knight Sir Eustace d’Aubrichecourt (see https://everything.explained.today/Eustace_d%27Aubrichecourt/). According to Penny Lawne in her excellent biography Joan of Kent, Eustace was “a professional soldier of considerable ability and had served with Prince Edward [to be known as the Black Prince] in Gascony and on the Poitiers campaign.”

It was after the drafting of the Treaty of Brétigny in May 1360 that many soldiers were left stranded and the free companies formed. Eustace was captured in 1359 but bought his freedom (he was now a wealthy man) and rejoined the English forces in January 1360. He was still only 26 years old in May that year when, after the drafting of the Treaty of Brétigny, he returned to England to be rewarded for his good service. The benefits of freebooting to the king’s coffers were far too advantageous to be frowned upon. To read more go to the following sites: free companies and here Free company – Wikipedia. Sir John Hawkwood his White Company, see John Hawkwood – Wikipedia, was perhaps the most famous and successful of them all.

But Sir Eustace formed his company of Hainaulter freebooters rather earlier, after the Battle of Poitiers, and began his marauding in Champagne. They attacked and plundered in the towns and countryside, and stole castles they then forced the rightful owners to buy back for enormous sums. On one occasion he captured a town where he found 3,000 barrels of wine and made himself very popular with the nearby English forces by sending the barrels to them. (See The Black Prince by Michael Jones, page 251/52. ) Oh, he was quite a lad….but most probably what we would now call a wrong ‘un. As far as Elizabeth de Juliers was concerned, perhaps she wanted what we so vulgarly term today as “a bit of rough”.

Eustace was captured in 1359 but bought his freedom (he was now a wealthy man) and rejoined the English forces in January 1360. He was still only 26 years old in May that year when, after the drafting of the Treaty of Brétigny, he returned to England to be rewarded for his good service. After all, the benefits of freebooting to the king’s coffers were far too advantageous to be frowned upon.

Dashing Eustace appears to have presented Elizabeth with sexual temptation so strong that she renounced her vow and emerged from seclusion to marry him. Lawne writes of Eustace that he was “an ambitious and unscrupulous soldier, [who] lost no time in pressing his suit”. Well, ambitious and unscrupulous soldier or not, he obviously had something that set Elizabeth’s heart racing. After eight years of seclusion she was still young and in full possession of all her hormones. Perhaps the dashingly dangerous Eustace, charged to the full and bristling with testosterone, was simply too much to resist. Whatever, there’s no hint whatsoever that she was pushed into the match, nor, as far as I can find, did the couple seek the king’s permission, which they certainly should have done because she was of royal blood. To say nothing of also being the widow of one of Edward III’s tenants-in-chief, the 3rd Earl of Kent.

It isn’t known when she and Eustace met, and Lawne wonders if it was during this summer of 1360 that he visited his friend Sir Thomas Holand, a Founder Member of the Order of the Garter and husband of Elizabeth’s sister-in-law Joan of Kent. Joan had inherited the earldom of Kent on the death of her only brother, Elizabeth’s husband John. She was now Countess of Kent in her own right, and Elizabeth was the Dowager Countess.

On page 45 of Goodman’s Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent it is suggested that the Holands would have encouraged Elizabeth to take the vow of chastity in the first place because they feared she might marry again and a new husband would benefit from the dower lands that would otherwise come to them (and thence their children) when she died. I cannot say whether this is correct or not, except that I’m sure they’d have kicked up a stink of some sort if they’d opposed the d’Aubrichecourt match. As far as I can tell, they didn’t. At least they don’t seem to have opposed it, but given the shenanigens around their own marriage they’d have needed a great deal of gall to carp about this second unorthodox winning of a royal bride.

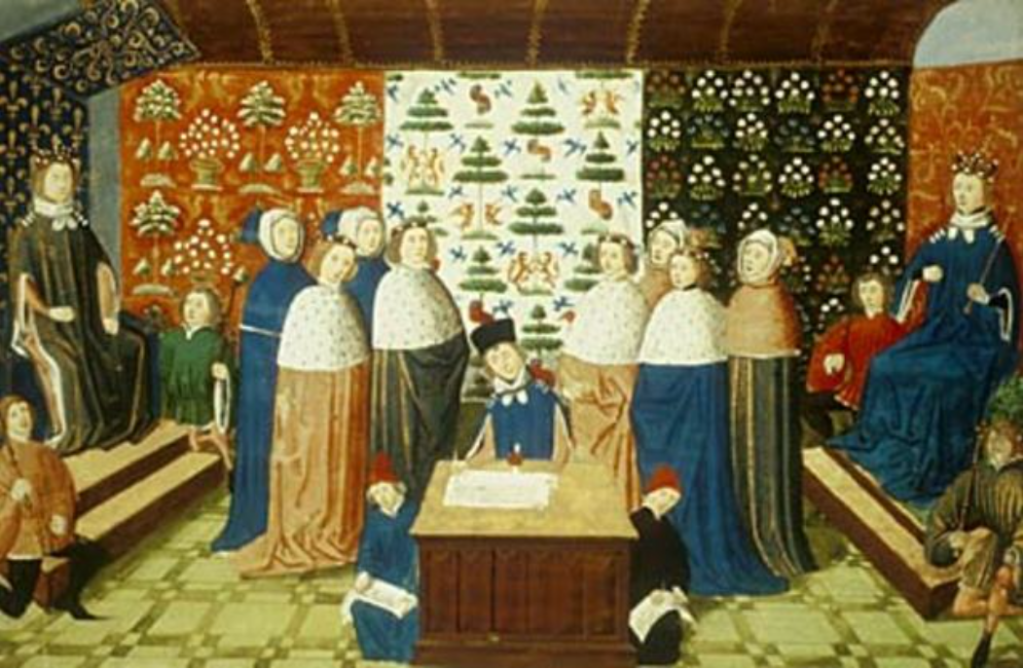

Let me explain. Joan of Kent’s marital history hadn’t been in the least conventional either, as you can read here—A history of The Holland Family (englishmonarchs.co.uk). She and Sir Thomas Holland created one of English history’s most memorable scandals, and I think it is safe to say that he was her greatest love. He was only from a gentry family of Lancashire and was also the seneschal of the second husband Joan had been forced to wed by her outraged family when they learned that she had—without seeking permission from her family or the king—contracted a low union with a mere seneschal. This other husband was William Montacute, who in 1344 succeeded his father to become 2nd Earl of Salisbury. Like Thomas Holand, he too was a Founder Knight of the Order of the Garter. Please note that I do not include Eustace d’Aubrichecourt in these references to the Order. There is a good reason.

Joan was only 12/13 when she met Thomas Holand, whereas he was 26! Shocking by our standards, yes, but back then girls were reckoned to be ready for marriage at 12 and childbearing at only 14, so it’s my guess that Joan, who was very beautiful, was probably precocious. Certainly she knew that she wanted Thomas Holand and after a very secret marriage (presumably consummated) she fought for a number of years to stay with him. And he, needless to say, fought to keep her. It was a very unequal match socially because while he was merely gentry from Lancashire, she was the granddaughter of Edward I—through his second marriage to Margaret of France—as well as a cousin of Edward III. She was also one heck of a catch for Thomas and there were considerable legal tussles. Eventually the Pope decided in Thomas’s favour and poor William (who wanted to keep his lovely wife) lost out. Thomas and Joan were at last able to live together.

The similarities between the Holand marriage and the one Elizabeth sought are obvious, except that Elizabeth had taken a vow that precluded, absolutely, any thought of remarriage.

At the time of Elizabeth’s chosen wedding day, Michaelmas 1360 (coincidentally Joan’s 33rd or 34th birthday), Thomas was on the point of being elevated to Earl of Kent in right of his wife. He’d come a long way from his origins, but as the cruel vagaries of fortune would have it, he’d die of illness on campaign at Rouen on 28 December 1360, only a few months after becoming earl. He was 46. (Elizabeth wasn’t without personal grief at this time either, for her father, the Duke of Jülich, would pass away two weeks before Thomas.)

Widow or not, Joan retained the Kent title, which was hers by right, and on her death in 1385 it would eventually pass to her elder son by Thomas, another Thomas Holand. And as she didn’t take any vows to the contrary, she was free to marry again. Her next and final husband would be none other than Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales—the Black Prince. See here. They would become the parents of King Richard II. But that’s all another story, for it is with Elizabeth de Juliers’ marriages that I am primarily concerned now. However, I felt it necessary to add the history of Joan of Kent, who shines brightly through the centuries, because she and Elizabeth were sisters-in-law….and both had set their hearts on a man they shouldn’t want at all. And were prepared to go through a storm of scandal in order to have their way.

Lawne believes that Elizabeth was staying with the Holands when Eustace returned to England in May 1360 and so she was on the spot, so to speak, when he too was invited to stay with them. Cupid’s arrow found an instant mark. Well, it did in Lawne’s version of their story. What happened next was that within a month Eustace left for Calais (close to his family home in Aubrichecourt), where on 24 October 1360 he was one of the signatories who ratified the Treaty of Brétigny that had been drafted in May.

The Treaty of Brétigny was drafted on 8 May 1360 and ratified on 24 October 1360. Eustace d’Aubrichecourt was one of the signatories at the ratification.

But how did Eustace come to know Thomas Holand well enough to be invited to stay? Well, they were both very successful soldiers and had no doubt encountered each other a number of times, but according to Lawne the main thing that united them was that in 1348 they were both Founder Members of the Order of the Garter. This is a very awkward point as far as Eustace is concerned, as you will read in the coming paragraphs. But if Eustace was indeed a Founder Member along with Thomas Holand, then yes, they’d have been friends. The Knights were all close in one way or another, which meant that Thomas would also come into contact with his old rival for Joan, William Montacute. William appears to have remained fond of Joan throughout and was always her friend and there doesn’t seem to have been aggravation between her two ‘husbands’. Perhaps they could set aside such matters when they were involved in the affairs of the Order….and on campaign, where trust was essential.

Elizabeth and Eustace were to have a son, William d’Aubrichecourt, who was buried at Bridport parish church in Dorset (see Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, Beltz, page 91). I have no idea when William was born or when he died. Eustace, however, died in 1371 at Carentan, Normandy, so he and Elizabeth had about ten years together. She didn’t die until 1411.

Maybe, as is supposed about Thomas Holand with Joan, Eustace was motivated by ambition, and maybe, like Joan before her, Elizabeth simply fell hook, line and sinker. And maybe both men then fell in love with the highborn wives they’d won. Whatever, Elizabeth’s marriage appears at this point to have been content enough, with no hint that that she ever claimed to have been forced into Eustace’s marriage bed. I’d like to think that they were a loving couple who found ten happy years together. But I’m a soppy old romantic.

A lot of the above was prompted by reading Lawne’s supposition about how and when Eustace and Elizabeth met, and at that early point I had no reason to question her reasoning. But as I made more checks online and in my personal library, I began to wonder if Elizabeth de Juliers was quite the sweet little innocent she seemed.

Another version of the story is on page 166 of A Distant Mirror, where Tuchman makes no mention of the Order of the Garter for Eustace or of Elizabeth’s vow of chastity. Indeed, the latter is said to have been so impressed (and excited) by tales of the “young, bold and amorous” Eustace (he’d been leading his free company of marauding brigands all over enemy territory like a nasty rash) that she sent him horses, gifts and passionate letters which urged him to ever greater exploits. This sounds rather like the over-excited present-day fans who deluge letters and gifts upon celebrities and, it seems, offer themselves on a plate as well.

Consequent to the drafting of the Treaty of Brétigny in May 1360, Eustace was released from capture by the French. He returned to England that same month of May, and he and Elizabeth married in September. That is fact. I’m sure Joan and Thomas weren’t taken by surprise. How could they not have known what was going on with the chaste, retiring widow of Waverley Abbey? If Froissart knew, then it’s a fair bet everyone knew! (See page 244 of Michael Jones’s The Black Prince, where Froissart is quoted at some length about Eustace’s exploits. The quote is from Book 1, 1322-77, of Froissart Chronicles—page 161 in my 1978 copy of the Penguin Classics version.)

But what do we really know about Sir Eustace d’Aubrichecourt, not least concerning the Order of the Garter, of which he is so widely credited as being a Founder Member?

In fact, when it comes to that, just how many d’Aubrichecourts were there?

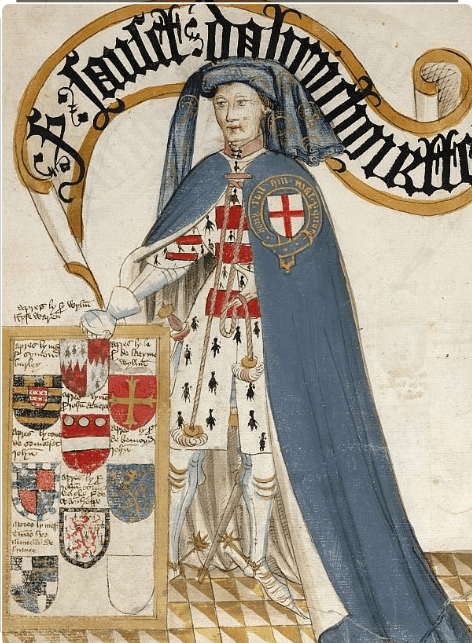

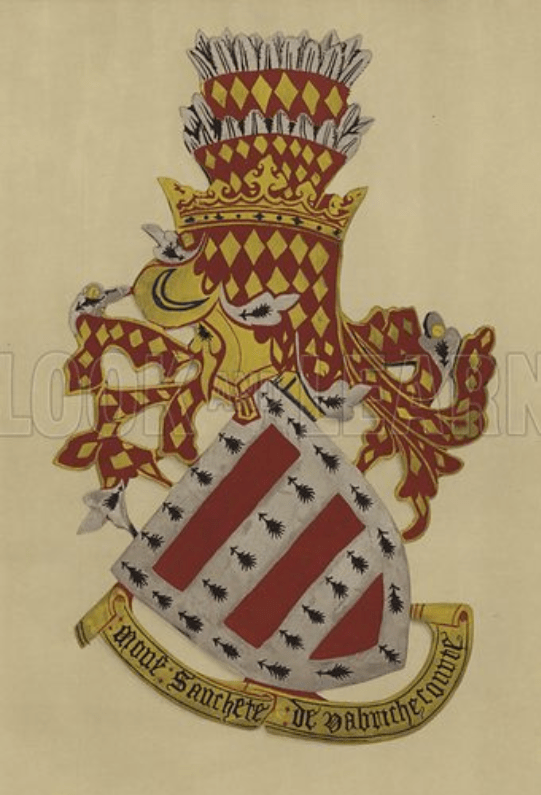

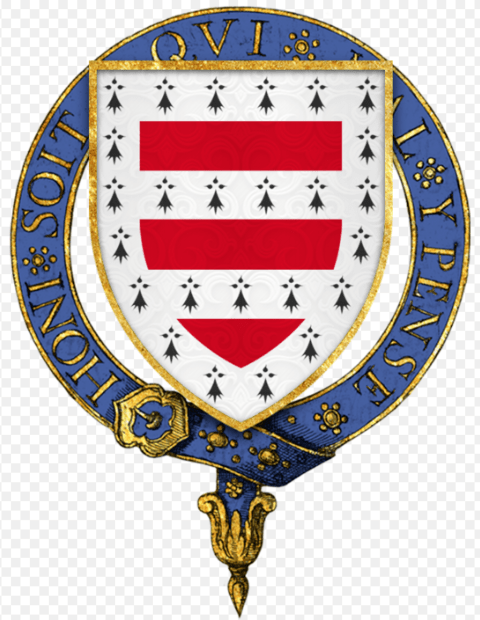

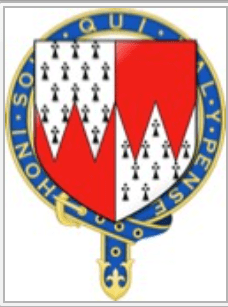

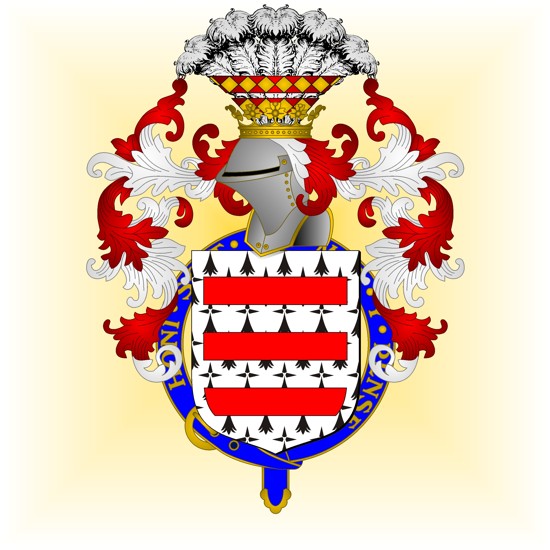

I am a little confused by the constant association of Eustace with the Order of the Garter. He is given this honour all over the internet and in books by respected historians. But would such a ferocious freebooter really be suitable for the most illustrious and premier chivalric order in the realm? In the book by George Frederick Beltz, Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter a d’Aubrichecourt was indeed a Founder Knight of the Order (number 25, page 90), but it isn’t Eustace. Enter his elder brother, Sanchet (see here). And it is Sanchet who is illustrated in the famous 15th century Garter Book of William Bruges.

Incidentally, the brothers’ home town of Auberchicourt, in the département du Nord, Hauts-de-France, is proud of its connection with Sanchet, as you will read here. The article can be translated into English on Google, and reveals that “the city was represented at [our, i.e. of the UK] Prince Philip’s funeral by one of its lords, Sanchet d’Abrichecourt, a founding member of the Order of the Garter.” By this is meant that Sanchet’s arms are on display in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, with the stall plates of all the other Knights of the Garter, and so would have “watched” the proceedings at Prince Philip’s funeral.

So, regarding the Order of the Garter, I have to nurse great doubts about Eustace, so often labelled a Founder Knight of the Garter. His brother was indeed such a member, but Eustace certainly wasn’t. There was only ever one d’Aubrichecourt who was a Founder Knight of the Garter, although there was at least one other later knight, as you will see below. So maybe it was through Sanchet that Eustace met and became friendly with Thomas Holand? Thomas was the 13th Founder Knight and Sanchet the 25th, both being inducted at the very beginning in 1348, and they were highly likely to be good friends. There’s no sign of Eustace among the Garter stall plates of St George’s Chapel, but Sanchet’s plate is still there. You’ll find a list of the Founder Knights at this link List of the Knights of the Garter (1348-present) (heraldica.org).

On page 304 of his Yale English Monarchs contribution Edward III, Mark Ormrod also questions the problem of Sanchet and Eustace, and concludes they were actually one and the same person. He writes: “I owe to a forthcoming publication by Richard Barber the identification of the mysterious ‘Sanchet’ d’Aubrichecourt as Eustace, and my inference that some of the more obscure founder members (of the Order of the Garter] were set aside in favour of others rather than, as usually argued, vacating their positions through early death.”

I haven’t heard of Knights of the Order being set aside in favour of others, unless they were traitors and had been expelled, as happened with Joan of Kent’s younger son, John Holand, Earl of Huntington, (see https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/2014/12/03/whos-the-great-granddaddy-then/) who far from being a traitor supported the cause of his half-brother Richard II, the legitimate king, against the usurper Henry IV in the Epiphany Rising of 1399-1400.

Incidentally, on page 19 of another of Ormrod’s works, The Reign of Edward III, also published by Yale, Ormrod writes: “….the original twenty-six members [of the Order of the Garter] included some obscure English and foreign knights such as Sir William Paveley and Sir Sanchet d’Abrichecourt….” So Ormrod was sure enough of Sanchet in this 1990 publication, where Eustace doesn’t get a mention at all. Exactly the same text appears in the same book’s 2005 publication by Tempus.

At this point I had no idea when Sanchet died, but his successor in the stall in St George’s Chapel, Sir William Fitzwaryne/Fitzwarin, passed on in 1361, which indicates Sanchet’s death some unknown period before then. The year 1359 is associated with the start of Sir William’s tenure. But then please note that the l’Observateur article above states: “Born in 1330 near Bugnicourt and lord of Auberchicourt, he [Sanchet] died at the age of only 19, one year after the creation of the Order of the Garter.” If this is so, then his tenure of the stall at St George’s was very brief indeed, and Sir William Fitzwaryne’s very much longer than previously seemed to be the case.

Before reading the l’Observteur article I had no idea that Sanchet may have passed away at such a young age, but even so, why should anyone should suggest that he’d been shoved out? My guess had been hat he had died at some unknown date before Eustace and Elizabeth were married, and therefore couldn’t have been present at their wedding.

I don’t find anything ‘mysterious’ about Sanchet. To me he seems a straightforward elder brother who died young and was a Founder Member Knight of the Order. It’s this widespread insistence upon Eustace being the Founder Knight that isn’t straightforward!

Nor did I know to which forthcoming publication Ormrod is referring above,* but Richard Barber’s 1978 Edward: Prince of Wales and Aquitaine contains references to both d’Aubrichecourt brothers, Sanchet and Eustace, with no hint of a problem in the identification. But at the same time Barber avoids all mention of the Order of the Garter for either brother. Mark Ormrod’s book was published in 2011, so the unnamed Barber work is post 2011.

I therefore cannot agree with Ormrod or, seemingly, Barber, that there was only one man all along, because there definitely appear to have been two. Sanchet wasn’t set aside from the Order, he died and (only 19 or not) left two well-identified and recorded sons: “Sir John Dabrichecourt, MP for Derbyshire and Constable of the Tower (1413-1415) and Sir Nicholas Dabrichecourt, Esquire of the Body to Edward III, MP for Hampshire and Constable of Nottingham Castle.”

Sanchet’s son Sir John was also part of John of Gaunt’s affinity, see The Lancastrian Affinity 1361-1399, page 37 note 127, and other references in the same book, including details of Sir John’s marriage. And Goodman, in his John of Gaunt, specifically refers on page 179 to Sir John d’Aubrichecourt as Eustace’s nephew. For that to be so, Eustace had to have had a brother! There is no mention of the Garter for Eustace, but as there was a d’Aubrichecourt Founder Member (see above illustration from the Garter Book), then I can only conclude from the ample evidence that it was Eustace’s elder brother, Sanchet.

Oh, perhaps I should also point out that at the history of parliament online the author (C.R. – I haven’t identified him/her) refers to Sir John as either Sanchet’s son or nephew. C.R. is taking no chances!

Eustace and Elizabeth are credited with just the one son, William. So surely it has to be wrong for the d’Aubrichecourt brothers to be conflated into one person. Sanchet had two legitimate sons, Eustace had one. End of argument.

On page 128 of The Black Prince, Michael Jones also lists Eustace among the Founder Members of the Order of the Garter. And on page 244 he writes: “‘the bold and amorous’ Sir Eustace d’Aubrecicourt [sic], a knight of Hainault, a Founder Member of the Order of the Garter and companion of the Black Prince at Poitiers, turned brigand and with such élan that he won the love of the widowed Isabelle of Juliers, niece of queen Philippa of England….” No mention of her vow of chastity.

Jones goes on to quote Froissart’s version of the enthralled Isabelle showering her hero with war horses, gifts and passionate letters. I note that Jones makes no mention whatever of Sanchet d’Aubrichecourt, who was so obviously the Founder Member of the Order of the Garter and who is so clearly illustrated and identified in the 15th-century Garter Book and elsewhere.

I’m satisfied with my conclusions about Eustace and the Order of the Garter and believe that Elizabeth’s vow of chastity began to wobble when she heard of Eustace d’Aubrichecourt and his freebooting escapades. (By the way, Froissart appears to hint that Eustace was equally as excited by the flattery he was receiving from Elizabeth. They may have aroused each other from a distance. Desire, sight unseen, so to speak. Or maybe they’d even met before 1360?) Elizabeth was certainly carried away by the emotions Eustace’s fame stirred, and I think she made certain they both stayed at the Holand residence at the same time. And when she actually saw him, her hormones went into overdrive! She wanted him, and he was certainly not averse to marrying such a desirable bride.

But all wasn’t to go well. By breaking her vow of chastity and indulging in “carnal copulation” with Eustace, Elizabeth was in sin. Heavy penalties were imposed on her (see page 47 of Goodman’s Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent for details, and pages 45-49 for a lot more about Eustace and their marriage). Maybe it all proved too much, especially for Eustace, who soon resumed his military career and while abroad this time fathered an illegitimate son named François, whose mother is unknown. Eustace died after 1 December 1371. Goodman’s book does, however, differentiate between the d’Aubrichecourt brothers, and states that Sanchet was the Founder Member of the Order.

So the notorious but romantic marriage of Michaelmas 1360 had lost its fire and when Elizabeth eventually died it was with her first husband, John, 3rd Earl of Kent, that she chose to lie. A happy ending there wasn’t to be. It was a sad conclusion to what I had hoped would be a wonderful exception to the rule.

* Since dragging myself (and you) through all of the above, I have now traced the work by Barber to which Ormrod refers. It is Edward III and the Triumph of England: The Battle of Crécy and the Company of the Garter (London 2013).

I have not read it, but I have happened upon a review that confirms my own amateur research concerning the d’Aubrichecourt brothers. You will find this review here. It certainly shoots Barber down in flames, and therefore, by association, Ormrod. If indeed Ormrod really believed Sanchet and Eustace were one and the same, which, by his own footnote (see above) he certainly appeared to do. It also shoots down in flames all the other respected historians who credit Eustace with being a Founder Member of the Order. Imagine their response had an amateur proved them wrong!

So there were two brothers, and Sanchet, the elder, died at only 19, barely one year after becoming a Founder Member of the Order. Younger brother Eustace was the fierce tearaway who won himself a royal countess.

So, one way or another, the decidedly peculiar mystery of the brothers d’Aubrichecourt is solved. But it’s still peculiar!

Leave a comment