Reblogged from A Medieval Potpourri @ sparkypus.com

A medieval scribe busy scribing. Royal MS 18 E. III, fol. 24r The British Library, London

THE SETTING

Following the sudden death of King Edward IV (1442-1483) at his palace of Westminster on the 9th April 1483 an unseemly scramble ensued to get his son, now King Edward V, from where he was residing at Ludlow Castle, then in the Welsh Marches but now Shropshire, to London as well as crowned at the earliest opportunity. Why this unseemly haste? All would become clear as the situation evolved. The late king’s widow, Queen Elizabeth Wydeville and her family tried to circumnavigate Richard duke of Gloucester, High Constable of England, Great Chamberlain of England, and High Admiral of England later Richard III, who had been named as Lord Protector in a codicil added to his brother’s final will, and prevent him taking up his rightful place in that position. In the main our knowledge of the events that took place over those few days evolve from the accounts of three commentators, the Croyland Chronicler, Dominic Mancini and Polydore Vergil. They all differ in some, admittedly small, respects, with the Croyland Chronicler and Vergil showing a hostility towards Gloucester, which, particularly in Vergil’s case, is quite astonishing. Let’s take a closer look at all of them and especially the points where their accounts differ.

DOMINICO MANCINI

Mancini was an Italian born scholar and chronicler who wrote closest to the time because, as happenstance would have it, he chanced to be present in England in the exact time frame between Edward IV’s death and the coronation of Richard III. He was the author of De occupatione regni Anglie per Ricardum tertium libellus (A little book about the taking of the realm of England by Richard III) written in Latin, and penned for his patron, Angelo Cato, Archbishop of Vienne. Unfortunately in the first translation of Mancini by Dr C A J Armstrong (who discovered the manuscript in Lille in the 1934) ‘occupatione‘ has been translated as ‘usurpation’. This has been corrected by Annette Carson in her more recent translation. Indeed any quick search for the latin occupationewill turn up the translation ‘occupation’ which is clearly what Mancini intended or why else did he simply not just use the word ‘usurpation‘ – a word which has not changed in meaning – in the first place? This is an important point because Dr Armstrong’s interpretation of the word occupatione would imply that Mancini saw Richard from the get go as a usurper when perhaps that was simply not the case Was Dr Armstrong aware and perhaps swayed by the recent conclusions from the 1933 examination of the bones kept in the Westminster Abbey urn by Lawrence E. Tanner and Professor William Wright who more or less prematurely identified them as being the remains of the sons of Edward IV, thus strengthening the belief they had indeed murdered by their uncle, Richard III ? Mancini is described by Livia Visser-Fuchs as appearing to be ‘free of personal prejudice, setting out to report the truth as he saw it; he wrote in the knowledge that Richard’s coup had been successful, but without the animus of later commentators writing after Richard’s downfall’ which makes a refreshing change from the usual bile and venom spat out by later chroniclers and historians aimed at Richard Duke of Gloucester later Richard III. Nevertheless although our good man Mancini is said to have shown ‘no personal malice’ towards Richard he naturally, of necessity, relied heavily on the information supplied to him by others who were not quite so neutral for various motives of their own. For example although in England at the time he was certainly not among Edward V’s entourage at Stony Stratford nor at Northampton yet he clearly seems to have been outstandingly au fait with what took place at those two places so it’s evident that he had quite a prolific tête-à-tête with someone who had been. The question was who? Who was his informant and importantly did they give him an honest, unbiased account? I would suggest the informant may have been Dr Argentine(c.1443-1508), Edward V’s physician, who had been with him at Ludlow and would have been among the young king’s party accompanying him to London. We know Dr Argentine had returned to London with the royal party because he visited the young Edward in the royal apartments at the Tower of London where he was later lodged. Although Mancini was not a fluent speaker of the English language he would have been able to converse with ease with the Latin speaking doctor. Ergo this could very well mean that the version of events as described by him were coloured by the perceptions of Argentine, who had connections to none other than John Morton, Bishop of Ely. To use modern parlance Mancini had no particular skin in the game – other than to slightly paint the English in general as a right bunch of immoral rotters particularly their king, Edward IV – but we must bear in mind, when considering his version of events, his contact with Dr Argentine, who as it transpired, very much did. Indeed Dr Argentine would go on to do extremely well under the Tudor regime being granted a ‘series of lucrative benefices, prebends, and canonries by his friends Archbishop John Morton and Bishop John Alcock of Ely as well as enjoying the fruits of royal patronage…’(2)’. He would eventually become the physician to yet another Prince of Wales, Arthur, Henry VII’s heir.

Prince Arthur (1486-1502) Henry VII’s heir. Arthur was to live and die at Ludlow castle where another Prince of Wales had once resided for a time (Unknown artist).

Dr John Argentine’s funeral brass. Chantry Chapel, King’s College, Cambridge.

Although Mancini seems, well to me anyway, at the forefront of these chroniclers in terms of reliability and unbiasedness he did make some errors. For example when he describes Edward IV, via the codicil in his final will, appointing his brother Gloucester as Protector of his children and realm. This is quite erroneous as the role of Protector of the Realm did not include the care or governorship of any royal children. This has been discussed at length by Annette Carson in her book Richard Duke of Gloucester as Lord Protector and High Constable of England. It was also Mancini who named William, Lord Hastings as being the informant who wrote to Richard apprising him of the shenanigans of the Queen and her family going as far as to urge him to ‘make haste to the city with a strong force and exact retribution for the wrong done to him by his enemies.’ No doubt Hastings took the opportunity to also appraise him of the ominous words of Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset, Edward’s uterine brother – ‘We are so important that even without the king’s uncle we can make and ensure these decisions’! It is also thanks to Mancini that we know Richard explained, to a no doubt shell-shocked Edward, that the very men he had ‘arrested were complicit in a plot to assassinate him: ….the duke himself accused these men of conspiring his death and preparing ambushes both in the city and on the road…which had been revealed to him by their accomplices…’

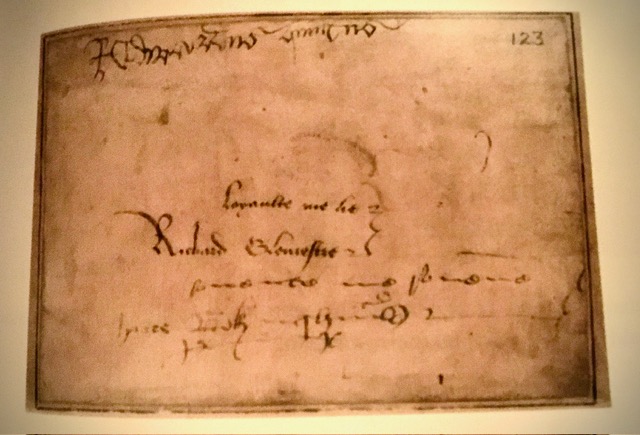

And so the royal party now resumed their journey towards London minus a couple of Wydevilles. If Edward held on to any hope that his mother might be there, at the end of his journey, to meet and comfort him, he was soon to be disabused. A tangible and poignant reminder of this journey has survived in a piece of parchment inscribed with the three signatures and mottos of Edward, Richard and Harry duke of Buckingham. At the top is the signature of the young king, followed by Richard’s with his motto ‘Loyaulte me lie’ /Loyalty binds me) and Harry Buckingham’s ‘Souvente me souvene’ /Remember me often). How the conversation, and who instigated it, led up to this moment which may have been an attempt to mollify Edward, we can only speculate. But it does remain, in a tragic story, a rare human touch.

The parchment with mottos. 1483. BL, MS Cotton Vesp. F xiii, f. 123. Now in the British Library.

How different things may have turned out if Elizabeth had stood her ground and been there to greet her son? It’s difficult, even over five centuries later, not to feel pity for this young lad caught up in a maelstrom of enormous and radical events none of which were of his own making. But I digress…. Following on from this turn of events we are informed that Richard wrote to the council and the mayor (of London) to defuse ‘an ill rumour that was being circulated that he had brought his nephew not under his care but into his power with the aim that the realm should subjected to himself’. These letters explained this was not his goal but to save Edward ‘….and the realm from ruination; because the young king would have gone straight into the hands of those who since they had not spared either the life or honour of the father, could not be expected to have more consideration for the son’. Furthermore these actions had been taken for his own preservation, as well as that of the young king and his kingdom, for Gloucester was also taking steps to parry an imminent assassination attempt on his life. These aforementioned letters were read aloud to the Council and received well although Mancini did manage a little dig, commenting that there were some there who‘understood his ambition and his arts’ which seems a bit of an anomaly following on from his earlier descriptions of Gloucester unearthing plots on his life and, naturally, taking steps to defuse them. Perhaps he thought Richard should simply roll over and await the dagger in his back? Still onwards… There then follows narrative of the arrival in London of the royal party and later events which we won’t go into here. Mancini tells us the royal party were accompanied by four wagonloads of arms with the Queen’s brothers and sons insignia on them which had been stored at convenient locations on the route to be utilised in ‘falling upon the duke and killing him’. However Mancini attempts to explain this away with the excuse they had been collected earlier for use against the Scots. Frankly this explanation sounds a bit dodgy to me. These arms meant for a possible Scottish campaign happening to be conveniently stored on the very route the royal party took as well as inscribed with Woodville insignia and found in the very nick of time? This really does stretch credibility to its zenith and begs the question was this explanation for the Woodville cache of weapons given to Mancini by someone who had had the time to dream it up?

Now we turn to the Croyland/Crowland Chronicler....

It was the Croyland Chronicler who pointed out the precise moment in time that things in London – in the aftermath of the sudden death of Edward IV – begun to get tricky. People were jockeying to get their positions consolidated before the arrival of the Protector. The Chronicler described how ‘various arguments were put forward by some people as to the number of men which might be considered adequate for a young prince on a journey of this kind. The more foresighted members of the council thought that the uncles and brothers on the mother’s side should be absolutely forbidden to have control of the person of the young man until he came of age. They believed that this would not easily be achieved if those of the Queen’s relatives who were most influential with the prince were allowed to bring his person to the ceremonies of the coronation with an immoderatenumber of horse’. William Lord Hastings, Captain of Calais, protested that ‘he would rather flee there (Calais) than wait the arrival of the new king if he did not come with a modest force’. The queen then instructed her brother Anthony Earl Rivers, then at Ludlow with Edward, that they should come with no more than two thousand men.

Richard had written letters of condolence to the queen before he begun his journey to London stopping off at York where a funeral ceremony was held. He bound by oath himself and all the nobility of the area in fealty to his nephew now Edward V.

In Croyland’s account when Gloucester reached Northampton he was joined by Harry Stafford duke of Buckingham. Earl Rivers – plus Edward V’s uterine brother, Richard Grey – also joined them to explain they had been sent by his nephew to submit everything that had done to Richard’s judgement. First of all things were convivial with Richard greeting them ‘with a particular cheerful face and merry face’. As night fell they all departed to their various lodgings. Here the accounts of Mancini and Croyland differ. According to Mancini, Rivers and Grey were arrested at the dawning of the next day. However according to Croyland they all set off together for Stony Stratford and it was when they drew near (apud) to their destination ‘Behold!’ (Et ecce!) Rivers and Grey were arrested and taken North. Gloucester and Co then continued into Stony Stratford where they also arrested Thomas Vaughan, Edward’s chamberlain, and other servants who attended him. Edward was still treated with the reverence due to a king and it was explained to him that these things were done as a precautionary measure because Gloucester had discovered that those close to Edward were plotting to destroy him. The rest of the king’s household were told to depart and not come near to the king on pain of death.

In the morning news of this reached London and the queen – with her other children in tow including her elder son, Thomas Grey, marquess of Dorset – he who had so recently pronounced how ‘important’ they were – hastily took herself off into sanctuary in Cheneygates, the luxurious Abbots House in the precincts of Westminster Abbey.

Entrance to the courtyard where Cheyneygates stood. Elizabeth and her party would have made their way to Cheyneygates through this doorway.

A few days after this the king’s party and Gloucester reached London where Edward was placed firstly in the Bishops Palace and afterwards in the royal apartments at the Tower of London which, it should be noted, was the normal place for a monarch to reside prior to their coronation. We shall leave the Croyland Chronicler at this stage.

So far we have looked at the events at Stony Stratford and Northampton from the viewpoints of two main primary sources. There is a third secondary source that gives an account of these matters – that of Polydore Vergil/Polidoro Virgili (c1470-1555). Vergil, an Italian, arrived in England in 1502. Henry VII evidently took a shine to him after meeting him and he ‘ever after was entertained by him kindly‘ (3). Henry requested him to write a History of England– which he did – The Anglica historia.

Henry VII 1457-1509. Unknown Artist. National Portrait Gallery, London.

His narrative – begun in 1508 and completed about 1512-1513 – although there was eventually several other editions – being written at the request of the then king of England can scarce be taken as that of an unbiased narrator. He also listed Thomas More as a friend which should ring alarm bells. Despite the fact that he ‘obtained a good deal of contemporary information from courtiers close to Henry VII’ and thus should be viewed with caution his version of events remains highly influential and often quoted by historians. As Barrie Williams wrote – ‘For the first sixteen years of Henry VII reign he had to rely on the memories and information supplied by contemporaries. Sir Reginald Bray, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster to Henry VII and Christopher Urswick, Dean of Windsor 1495-1522 feature prominently in Vergil’s account of Richard III’s reign, information for which they probably supplied themselves. It hardly be remarked that More, Morton, Foxe, Bray and Usrwick were all strong partisans’. This should surely ring even further alarm bells and massive ones at that (4).

For those who have the time, inclination and strength, here is a link to the relevant part of Vergil’s history relating to Richard III. Mirroring the modus operandi of his friend, Thomas More, Vergil concocted long speeches made by principal characters consisting of their most innermost and private thoughts which is somewhat of a surprise considering these thoughts were never documented. An explanation of him having access to the privy thoughts of people long dead may be that he was either psychic orhad a handy diary of Richard III’s stashed away. These ‘speeches’ unfortunately led to some folk taking them at face value and getting thoroughly confused – as you do. Historian William J. Connell noted that the ‘inevitable results of his account of events often read quite differently from those found in contemporary chronicles, giving rise to the famous and unfounded allegations by his critics that he had burnt older sources in order to hide his errors’ (5). Oh dear. Neither would he escape castigation in his time – John Bale writing in 1544 accused Vergil of ‘polutynge oure Englyshe chronycles most shamefullye with his Romishe lyes and other Italyshe beggerye‘ (6). Ouch!

To give a brief résumé of Vergil’s account: Following on from Edward IV’s death, William Lord Hastings sent messengers to Richard who was then at York. They inform him of the codicil in Edward’s last will that entrusted the whole kingdom to him until Edward Jnr should come of age and urge him to take the boy into his care asap and bring him to London. Vergil knows that it is this very precise instant ‘a desire to claim the kingdom for himself was kindled’ in Richard. However he puts the matter on the back burner for the time being and sends letters of ‘warm regard to Elizabeth comforting her with many words and making extravagant promises’. To cover up his evil plan and to make himself appear as a man of honour and integrity ‘he summoned the nobility from all parts to assemble in the city of York and commanded them all to swear allegiance in the name of Prince Edward. He was the first to take the oath which he was soon afterwards to violate shamelessly; then all the rest swore solemn allegiance to their prince. When this was done, he immediately gathered a large body of armed men and prepared himself to make the journey’. Later in his narrative after painting Richard as evil personified he seems to feel it is necessary to acknowledge yet somehow explain away the good reputation that Richard had earned up until that time. Hence we have Richard performing a double volte-face and repenting of a life ‘badly led he begun to present himself as a changed man, that is to say pious, just gentle, civil religious and generous especially to the poor’. Any good acts such as ‘generosity, mercy and integrity’ were explained away as being Richard attempting to ‘win pardon from God for his sins…’ and to win ‘grace and favour among men’. This ignoble attempt to belittle Richard’s good deeds probably ranks as the highest disservice of all from the three chroniclers combined. But to return to Northampton and Stony Stratford…

In the interim Edward Jnr had set off for London from Ludlow with only a small retinue which seems odd as the queen had instructed Rivers to bring Edward to London with an escort of 2000. Still onwards…

At this point Vergil deviates quite a bit from Mancini and Croyland, for according to his version, Richard and Buckingham meet up in Northampton but without Rivers joining them. Richard informs Buckingham of his evil plan to ‘seize the throne’ and after Buckingham, as luck would have it, fails to ‘disparage’ the plan both men then ‘hurredly make their way towards the prince’. Upon their arrival in Stony Stratford Edward is ‘torn from his loyal followers, to the point of inflicting death….’ Following on from this and their arrival in London Richard is miffed that the Queen has inconsiderately legged it into sanctuary with her other children including the younger prince, Richard. Her unmerited action is of course down to her sex. Richard explains that ‘her actions amounts to a great culumny against us and the realm. We must of course make allowance for her sex which is the source of all this upset. It is up to us to heal this womanly disease that is worming its way into our Commonwealth…. ‘ After convincing everyone that the queen was the problem, which she was but not in the way Vergil portrayed, men of consequence were despatched to the sanctuary and ‘the innocent boy was snatched from his mother’s arms later to be murdered by the tyrant’. We will leave Vergil at this point.

Artist’s impression of the young Richard being dragged from his mother’s arms. The 19th century brought a deluge of impressive and poignant artworks depicting the fate of the princes as described by Vergil. This one is by Philip Calderon. Young Richard of Shrewsbury gazes tenderly at his mother while being yanked away by his arm by a portly gentleman in red – poor little blighter.

I’ll not repeat any of the speeches here but they can readily be found in Polydore Vergil’s Life of Richard III – an edition of the original manuscript. Edited and translated by Stephen O’Connor. Also here is a link to Barrie Williams article How Reliable is Polydore Vergil .

SUMMARY

So which are the primary sources we can rely on? Mancini seems on the whole reliable but on occasion let down by a bias which is almost petty. But I believe this was more the result of his contacts. Croyland is definitely biased and somewhat of an old misery – but in all fairness I hasten to add – it was not just Richard he was biased against. Anyone or anything north of the Watford gap was fair game to him – the north was the place ‘whence every evil takes it rise’ and the inhabitants ‘ingrates’. The mere sight of a block of Wensleydale cheese would have been enough to trigger him. Richard had made his home in the north and was thus a northern king (whereas Edward IV was a southerner and therefore ‘glorious‘) and his entourage/mob therefore unacceptable. To use his own turn of phrase ‘Quid Plura?’ Still in all fairness to him he did deign to mention the true reason for all the upset i.e. the secret marriage of Edward IV and Lady Eleanor Boteler/Butler née Talbot. It was this earlier and, according to the canon law of the time, legal marriage that upset the apple cart because clearly Edward could not have been married to two women at the same time. Thus his children with Elizabeth Wydville were bastards and unable to take the throne. However nothing daunted he dismisses Titulus Regus as a mere ‘certain parchment‘ roll and, furthermore, accused the author of ‘sedition and infamy’. Can the Croyland Chronicler be judged as trustworthy? If read bearing in mind that the writer is an absolute biased one then much knowledge of those turbulent days can be gleaned from him. We have a lot to thank him for frankly, especially for the fascinating minutiae that has come down to us from those times because of his reports. It is kind of touching that in those turbulent times he bothered to mention the death of the cellarer’s dog – ‘cruelly transfixed with arrows’. It is also thanks to him that we have the rather charming story of the young Duke of Gloucester discovering Anne Neville, his future wife, disguised in the dress of a kitchen maid – ‘in habitu coquinario’ – as well as the information, so often repeated by historians, of the distress of King Richard and Queen Anne ‘almost bordering on madness’ at the news of the death of their small son, Edward. Yes he does sometimes, well quite a bit actually, come across like the proverbial old maiden aunt with waspish comments such as those regarding the ‘vain‘ exchanges of clothing between Queen Anne and Elizabeth of York at Christmas 1484 but still, I’m inclined to like him. To borrow from his own words ‘quid multis immorer?…

Turning now to Vergil….

Despite his penchant for making up long speeches, claiming to know what was going on in Richard’s head and his closeness to supporters of Henry Tudor there may be a kernel of truth in his report. But his unnecessary over-egging of the pudding, absurd speeches and unquestioning blind adherence to those with their own axes to grind debases and, in my opinion, renders his account the least reliable of all.

And this compounds the tragedy of Richard III. For after his death and the last tragic Yorkist hooray at Stoke no-one was left to speak up for him to give a more balanced and truthful version of what happened. Then, as now, rumours can be the cause of much mischief and at their worst the catalyst for much injustice and even horrible violence. But still truth will eventually out and with the passing of the Tudor regime and the arrival of the early 17th century Sir George Buc comes galloping to the rescue armed with his massive tome The History of King Richard III. Sir George’s book has now been recently, and wonderfully, edited by the late Dr Arthur Kincaid and is thoroughly recommended. Ironically it was Sir George – whose grandfather fought and died at Bosworth – who discovered the Croyland Chronicle as well as Titulus Regus. Later in that century Horace Walpole would also add to the new debate with his Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard III. Now there is a veritable host of people fighting for Richard’s corner who at the very least bring a more balanced view to Richard’s story.

- Mancini, Domenico (b. before 1434, d. 1494×1514).Livia Visser-Fuchs. Oxford DNB September 2004.

- Argentine, John (c. 1443–1508) Peter Murray Jones Oxford DNB

- Vergil, Polydore/Polidoro Vergili (c1470-1555). William J Connell Oxford DNB 23 September 2004.

- Lambert Simnel’s Rebellion: How Reliable is Polydore Vergil? Barrie Williams. The Ricardian vol.6. p.79 p.p 118-123. 1982.

- Vergil, Polydore/Polidoro Vergili (c1470-1555). William J Connell Oxford DNB 23 September 2004

- ibid.

If you have enjoyed this post you might also be interested in:

The Bones in the Urn again! A 17th Century hoax?

CAN A PICTURE PAINT A THOUSAND WORDS? RICARDIAN ART

Marriage in Medieval London And Extricating Oneself Only You Couldn’t

Cheyneygates, Westminster Abbey, Elizabeth Woodville’s Pied-à-terre

:

Leave a comment