In late April 1388, John of Gaunt‘s son-in-law Sir John Holand returned to England from the Spanish peninsula, where he had been constable of Gaunt’s army. Gaunt had invaded the peninsula in pursuit of the Crown of Castile, to which he had a claim through his marriage to the Infanta Constanza. I am now going to relate three events that preceded this return, two of them that had nothing to do with the 1386/88 campaign in Spain and Portugal. All of them indicate that John of Gaunt, Shakespeare’s “time-honour’d Lancaster”, was prone to push ahead with a campaign even when it was failing and was at the expense of his men. His own glorification meant more than saving his men so they could fight again another day.

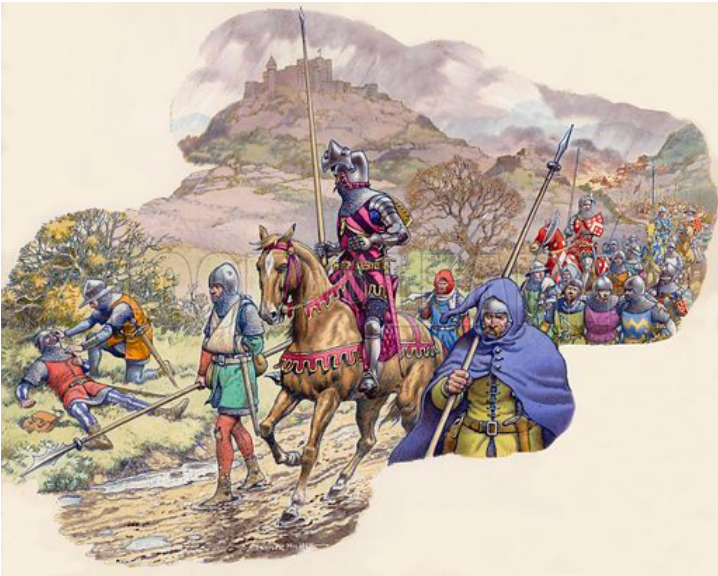

The first instance took place in 1373, when Gaunt embarked upon his infamous Great Chevauchée through France. There came a point when he had to make a decision about whether to continue or turn back. According to Armitage-Smith: “….The advance from Calais to Troyes had produced no engagements and no military result. He could go back, which would be inglorious, or he could go on, which would be useless….the Duke could not have peace with honour. He chose honour with disaster, and went on….”

In Davd Nicolle’s book The Great Chevauchée you’ll read the result of this decision: “….when John of Gaunt and his followers finally marched into Bordeaux on Christmas Eve 1373, they were a half-starved, bedraggled crew, although they are still said to have behaved with discipline….” They’d have been in far better shape, and there’d have been thousands more of them, if Gaunt had turned back when he should have done.

Now we move on to 1385, and Richard II’s successful campaign against Scotland. Gaunt’s royal nephew had conducted himself well, although his army was much smaller than his uncle’s. According to Arnold’s Richard II and the English Nobility, Richard II’s successful 1385 campaign into Scotland had reached Edinburgh. There he and his uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, fell out. Again. They didn’t get on most of the time. Gaunt wanted to forge ahead north to wreak more havoc on the Scots, but Richard knew the men of his and Gaunt’s armies were tired and the supply lines couldn’t sustain further conflict. He also knew that enough damage had already been done in southern Scotland. Apart from which, there was too great a risk of men perishing from illness, hunger and thirst. The argument ended when Richard told Gaunt that he, [Gaunt] could go on over the Forth if he wished, but “I and my men are going home”. Gaunt gave way and returned south with the king. Relations between the two men had gone from bad to worse. But if Gaunt had been in charge, not Richard, it’s clear there’d have been much more bloodshed and Gaunt’s army would have suffered.

Now, Richard II isn’t often given credit for common sense and compassion, but in this instance he displayed both. He put his men before all else, which is something Gaunt seldom seemed disposed to do. A year later, in Spain, a similar situation arose and once again he had to be confronted in order to make him do the right thing.

Gaunt’s ambition to secure the crown of Castile for himself is well-known. He’d married the Infanta Costanza, eldest daughter of Pedro of Castile, and when Pedro was murdered, Gaunt was presented with a claim to the crown through his wife. So in 1386 he embarked upon a great campaign to achieve this. He took with him a huge army, and as its constable he appointed his new son-in-law Sir John Holand. Sir John was Richard II’s half-brother. They both shared the same mother, Joan of Kent, who had died the previous summer.

The duke and Holand were close at this time, even though Holand’s track record was hardly admirable. Most historians dismiss him as a murderous, cruel, impetuous, hot-tempered, dangerous fiend who should be kept at arm’s length. Well yes, he had a quick temper and he had killed a man on account of it. He’d also been involved in another man’s death through torture, and later on wasn’t always too fussy about how he acquired lands. In fact, he could be quite unscrupulous when the mood took him, but as always with these things, the background and all the facts are rather hard to pin down. It’s often what isn’t known that holds the key to someone’s conduct. So he wasn’t a cherub, but nor was he the devil incarnate.

By the time of the Castilian campaign, however, Sir John had certainly calmed down a great deal. One thing always seemed to redeem him, his charm. As far as women were concerned, it was fatal, because he was able to seduce and marry Gaunt’s daughter Elizabeth. There had to be a shotgun wedding before Gaunt and his army set off.

As well as soldiers, there was a large contingent of ladies too, because knights often took their wives with them. Elizabeth certainly went. The duke clearly liked Holand enough to agree to the match, because notwithstanding the impudent bridegroom being the king’s half-brother, he had no title prospects and little land. At this point he certainly wasn’t worthy of Elizabeth of Lancaster. But the marriage seems to have been happy enough, until its later years anyway, when she placed her Lancastrian blood before her husband and his brother the king.

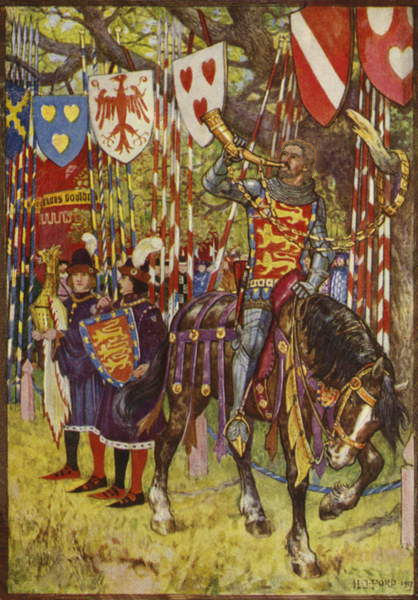

Like Richard II himself, Holand is seldom given credit for doing anything good or compassionate. In fact, he’s bad-mouthed as much as his royal half-brother, who is almost always condemned as a wicked half-mad tyrant. Today’s historians even condemn Holand for taking part in tournaments during the Spanish campaign, but tournaments were part and parcel of the lives of 14th-century nobility, on all sides of any dispute, and it was nothing for hostilities to pause while a showy tournament was arranged between them all. Afterward, of course, they’d fight like merry hell again.

Gaunt encouraged his knights to show off their talents in this way And one thing you could say of Sir John Holand was that he was a talented jouster. In the eyes of Froissart he was what we’d call today a superstar. He knew how to put on a great show on the tourney field, and he had the talent to carry it off.

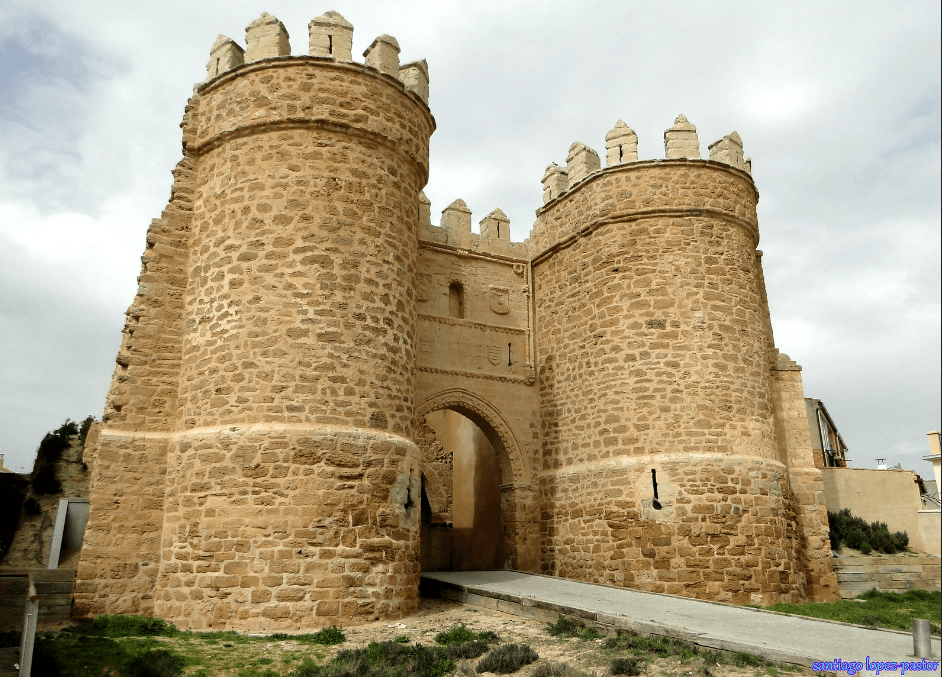

Anyway, I’ve written the above about John Holand because, as had happened the previous year in the Scottish campaign, illness and exhaustion struck this army of Gaunt’s. It was at Villalpando in the summer. Disease rampaged through the men (it’s believed it may have been dysentery, and that Gaunt himself was struck down as, possibly, was Holand too). A great number of Gaunt’s knights, officers and ladies had already lost their lives. But Gaunt continued the campaign, which by then was reaching a conclusion anyway. Gaunt himself was not going to wear the crown of Castile, he’d have to settle for one of his daughters receiving that honour. So why keep fighting?

Now, if John Holand had really been the terrible creature his fame insists, then he would hardly have been someone the stricken men would approach to beg him to persuade Gaunt to abandon the rest of the campaign. But they clearly knew they could approach John Holand, who did indeed sympathise with them and who did persuade Gaunt to abandon the campaign.

But if Holand hadn’t spoken to his father-in-law Gaunt, how long would it all have limped on? How many more men and ladies would have perished? As it was the soldiers were disbanded and told to make their way home, and Holand had the task of escorting all the surviving ladies (including his own wife) and many sick knights back north through Navarre to Bayonne. And then to England by sea.

Those are the basic facts of the campaign in the peninsula. Do you see anything wrong in John Holand’s conduct? No, nor do I. He paid attention to the men over whom he was constable, and did what he could to spare them. But some historians don’t view it like that. Oh no, In the same spirit as the infamously unfair treatment of Richard III, so they malign John Holand.

Here’s Jonathan Sumption: “….A substantial number [of men] decided to withdraw to Gascony. Their ringleader was Sir John Holand, who as Constable of the army was ultimately responsible for its discipline. Holand was a vain and hot-tempered playboy in his mid-thirties….who came before the Duke to tell him the temper of the men. Everyone knew, he said, that the invasion had failed and….There was no longer a cause to fight for. He himself intended to apply to the Castilian King for a safe-conduct to enable him to take his wife and anyone else who wanted to leave to the passes of the Pyrenees….” Hmm. That’s twisting it somewhat, methinks. John Holand would never speak to Gaunt in such a high-handed way. Nor was he a “ringleader”. Nor would he scuttle off and desert the duke by escaping danger with ladies and invalids. He was constable and had been approached by the sick and weak soldiers to come to their rescue. He knew he had to persuade Gaunt. Persuade, please note, not take huge liberties with.

In The Red Prince, Helen Carr has Holand faced with a fait accompli by the men. He certainly was not a ringleader of anything mutinous: “…John Holland came to Gaunt as he remained in his tent during this bout of melancholy [over all the deaths of those close to him during the campaign]….As Constable of Gaunt’s army, he [Holland] had received numerous complaints from scared, exhausted soldiers who were furious with the Duke of Lancaster and desperate to go home. Having watched the men sicken and die, Holland informed Gaunt that his men had decided to request permission from Juan Trastamára to travel through Spain to reach Gascony and then home….Over the next few days English soldiers began to desert the disease-infested camp at Villalpando…[Gaunt] was forced to come to terms not only with his failure to take Castile, but also with the massive loss of life….over 800 squires, archers, knights and barons perished at Villalpando….”

Once again Gaunt had pressed on at the expense of his men, but does he get the criticism? No. That unfair accolade goes to Holand, whom Goodman describes as having “….great charm and considerable ability, but he was violent, ruthless and self-seeking….” Name a 14th-century nobleman who wasn’t self-seeking! And Holand was a second son without a title or wealth. He had to carve his own career. If he’d simply hung around like a lemon, he’d have soon died destitute!

Steel qualified a little. “….The Hollands…[were] allegedly violent, selfish and avaricious characters….they were certainly violent but perhaps not remarkably selfish….” That’s damning with faint praise!

So there you have my three occasions when John of Gaunt thought more of his own glory than the wellbeing of the men over whom he was commander. Time-honour’d Lancaster indeed. As for John Holand, well, there was much more to him than historians would have us believe, and in Spain he behaved with honour. But no, the likes of Jonathan Sumption would much rather turn him into a scheming coward who deserted his father-in-law in his hour of need. Enough already!

My own opinion of both John Holand and Richard II is that they inherited their capacity for compassion from their mother, Joan of Kent. She was renowned at the time as the most beautiful woman in England, and she had a scandalous past that may or may not have been her own doing. When her Holand husband died she captured the heart of the great Black Prince, and thus Richard II was born. Joan was a very sensible and gentle woman who used her position to mediate and pour oil on troubled waters. She became much loved throughout the realm, but while she was accepted it was a different matter for her sons by her first marriage. Their real crime in the 14th century was to have risen to prominence and influence through her astonishingly advantageous second marriage. Thus she became Princess of Wales, and her Holand children were advanced accordingly. Not that John Holand was advanced with any particular haste!

He eventually rose to being Earl of Huntingdon and Duke of Exeter, and died rebelling in his half-brother’s cause in 1400, when Lancaster’s son, Henry of Bolingbroke, usurped the throne.

Leave a reply to refagan51 Cancel reply