A POST ESPECIALLY FOR HALLOWE’EN….

Here is a tale of murder most foul that I think suits Hallowe’en, even if it didn’t actually happen at Hallowtide. It’s based on fact, and I first found it in Lancashire Folk Tales by Jennie Bailey and David England. Since then, in one form or another, it has also turned up elsewhere.

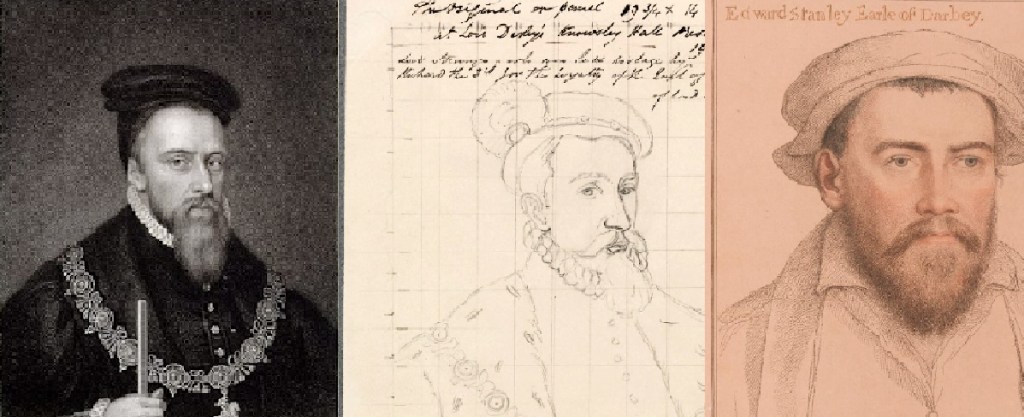

What follows is my interpretation of events, coloured by information I’ve discovered since investigating the story. The factual aspect concerns sly Thomas Earl of Derby and his equally disagreeable son, George, Lord Strange.

Thomas is the person of interest in the case, and yes, I really do mean that phrase exactly as today’s police would use it. For me, anything that kicks the traitorous turncoat regicide on the shins with an iron-spiked boot is OK by me!

According to the above book “….Thomas Stanley would never stoop to diplomacy when duplicity and brute force would suffice….” and “….[he was] a ruthlessly ambitious and scheming man who had switched sides repeatedly in the Wars of the Roses….” Each time to his own selfish advantage. So, not composed by the Thomas Stanley Fan Club!

Before I continue, perhaps I should identify the places concerned. Warrington is where Thomas Stanley built a contentious new bridge. The yellow dot immediately NW is Bewsey Hall, residence of the knightly Butler family (spelt Boteler in some sources). It was at Bewsey [Old] Hall that the dreadful murders were committed. Here you will find a description of the remains of the original medieval hall.

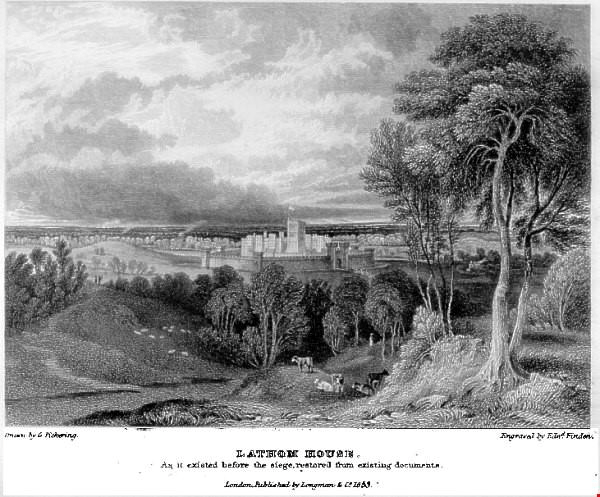

On the map the next yellow dot, to the west of Bewsey, near Ormskirk, indicates Lathom House (see here, here) and here). It’s a large and important Stanley seat, and in June/July 1495 was honoured by a royal visit when Henry VII, Thomas’s usurper of a stepson, made a progress through Lancashire. This was the occasion for which Thomas erected the above-mentioned contentious bridge.

The third yellow dot on the map, further north than Lathom Hall but actually closer to Liverpool, is Knowsley another seat of the same Thomas. It too was visited by Henry VII in 1495 and for this momentous occasion Thomas went so far as to provide brand-new “royal lodgings”. So what with this and the bridge, all told the visit cost him a pretty penny. But then, at the time he was particularly anxious to create a good impression on the first Tudor king, as you will read toward the end of this article.

Thomas Stanley, our bearded moustachioed villain, was created 1st Earl of Derby after the Battle of Bosworth of 1485, during which his sordidly pre-meditated treachery (together with that of his brother Sir William Stanley) brought about the death of the Yorkist king Richard III.

Anyway, it was ten years after Bosworth, when the Yorkist pretender Perkin Warbeck was causing Henry many sleepless nights, that the first Tudor king decided to make a summer progress through Lancashire. Possibly to show himself to his “loyal” subjects and warning them to think many times before deciding to support Warbeck. It was while he was away in the north that the said Warbeck made an unsuccessful landing at Deal in Kent. He would not be deterred from trying again in future. By claiming to be a returning Yorkist prince whom Henry wanted the world to believe to be dead at the hands of evil Richard III, Warbeck was a huge thorn in Henry’s side.

Thomas was aware of the impending royal progress well in advance, and also knew that Henry’s route to Lancashire from the south involved crossing the River Mersey from the Cheshire side. As things were, this meant a considerable detour in order for the king to reach Lahom House. The alternative was to use the unglamorous ferry that monopolised the crossing to and from the Lancashire town of Warrington. From Warrington the road led to Lathom House. Thomas considered the ferry to be unspeakably demeaning to the King of England!

The ferry belonged to a certain Sir John Butler of Bewsey Hall, 15th Lord of Warrington, with whom Thomas and his family did not have a good relationship. In 1493/4 Thomas’s son George (according to Lancashire Folk Tales the son was as disagreeable as the father) had already taken a member of the Butler family to court (see Lancashire Fines: Henry VII | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk) and won. At least, I think he won – I can’t sort out the legal medieval meaning of the Latin. Whatever, the dealings between Stanley and the Butlers of Bewsey Hall were not always amiable.

Then Thomas was inspired to build a brand new bridge exactly where it would best benefit the king’s journey. He purchased a plot of riverside land in Warrington that was directly opposite another plot that he himself already owned across the Mersey. The bridge was right next to the Butler ferry, and work on it was completed in good time for the royal progress to eventually pass over the Mersey unimpeded—with dignity intact.

Thomas wasn’t a joyous little soul even in a good mood, and annoying him was never a wise move, but this is what the incensed Butler did because the fancy new bridge was robbing him of his lucrative income from the ferry. It seems the Butlers had never taken challenges to their crossing lying down, so the 15th Lord confronted Thomas, who was at first conciliatory. This was because he feared a nasty littlet local fracas might encroach upon and ruin the royal visit. So he tried to fob Butler off by inviting him to join the company with whom Stanley himself would ride out to welcome the king’s great cavalcade.

Butler was not impressed and said some very rude and harsh things about the offer. He did this to high and mighty Thomas’s face and so infuriated him that Thomas decided the insolent fellow had to go—permanently.

I have now set the scene for the three versions of the murder, as related in Lancashire Folk Tales. My apologies for having taken so long to get to the point, but the foregoing is necessary to clarify everything that follows.

Here is version one. Thomas delegated his son George to carry out the awful deed. A discontented porter at Bewsey Hall was bribed to put a light in a window to guide George and a handful of fellow villains in a boat across the moat. Inside, he led them to Butler’s bedchamber, where they hoped to kill him as he slept. It didn’t matter to George that Butler’s wife Margaret and younger son, a baby named Tom, were also in the room. But their way was barred by Butler’s devoted chamberlain, Master Houlcroft, who stood guard at the bedchamber door and raised the alarm immediately.

A short but vicious sword fight ensued and George slew the unfortunate chamberlain at the threshold. By now Butler had awoken but had no time to make a getaway when George and his cronies fell upon him. He too was killed by George’s sword.

George was fired up so much that he wanted to kill the baby as well. But little Tom’s cradle was empty because a vigilant page had snatched the child away. At the main door of the house the page encountered the surly porter who demanded to know what he was carrying that was wrapped up so well. The quick-witted page replied that it was Butler’s head which George had told him to fix on a spike on the new bridge. The porter thought it sounded just the sort of thing George would order and let the page go.

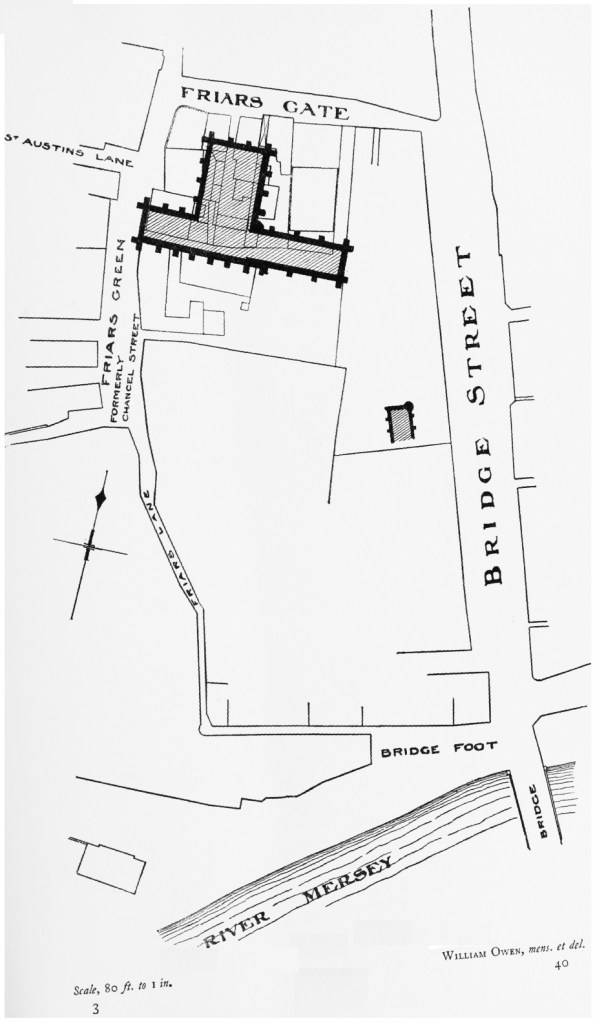

The baby was taken to the Priory of the Hermit Friars of St Augustine, see here and here.

The widowed Lady Butler, who had escaped from the bedchamber, went there as soon as she was able and carried her baby away. He grew up to marry and continue the Butler name. See Sir Thomas de Butler Of Bewsey (1461–1522) • FamilySearch and Thomas (Butler) Butler KB (abt.1461-1522) | WikiTree FREE Family Tree. Little Tom wasn’t the firstborn, he had an elder brother Michael who would die childless and doesn’t feature in this story.

As for the porter, well he was hanged from a convenient tree by either Thomas or George Stanley (or both together) to keep him from splitting on them. Serves him right.

Now for the second account of this dreadful tale. Everything is the same as above, to the point when Houlcroft is slain and George and his friends burst into the bedchamber. This time it isn’t a page who saves baby, but a burly footman who grabbed the baby from its cradle at the first sign of danger and hastened it to its nurse. The footman then held off the murderers with his fists until he was overcome and killed, but the nurse had escaped with the child and carried him to the same priory as in the first version. Lady Butler was so grateful to the footman that she had him buried beside her husband and his image carved upon the tomb. The baby grew up to continue the line, as in version one.

The third and final version of the story is rather different because there’s no mention of a bridge or a king, and no prospect of earldoms. To begin with it takes place well before the reign of Henry VII. I have found the relevant Butler’s recorded death as 26 February 1463, but usually just in the year 1463. This time it’s Thomas himself (at this point only the eldest son) who leads the killing raid on Bewsey Hall and wields the fatal sword.

It seems Thomas was one of seven children, and in their father’s frequent absences Thomas and William established themselves as top dogs. Especially Thomas. The pair were soon out of control, making their younger siblings’ lives a misery, particularly young John and their sister Margaret. For these unfortunates their only relief was when they visited nearby Bewsey Hall, home of John Butler, 14th Lord of Warrington, with whom the Stanleys mut have been on good terms at this point. The 14th Lord’s heir, another John Butler, was a few years older than the Stanley bullies and more than able to deal with them in kind. Thus humiliated, Thomas became young Butler’s implacable enemy. This signalled the end of the period of friendly dealings with Bewsey Hall.

Knowing that Margaret and Butler were attracted to each other, spiteful Thomas saw to it that she was forced to marry his “brutish” crony, William Troutbeck, 12th Lord of Dunham, see here. She’d had five children before Troutbeck was slain at the Battle of Blore Heath in 1459. As soon as she could she married John Butler, now the 15th Lord of Warrington, and they lived happily at Bewsey Hall. Please note, she wasn’t his first wife and he too now had children from a previous marriage, so neither of them was a starry-eyed innocent, but they were still in love.

Thomas was so enraged by their happiness that he plotted and carried out the awful events at Bewsey Hall. So, in front of his distraught sister he knowingly despatched her beloved husband and would have killed his own nephew had not fate intervened to save the boy, whether through the heroic offices of a faithful page or a nurse and loyal footman!

Right, I’ve presented the three accounts of what happened at Bewsey Hall and must now delve which one is likely the truth. Or at least try to reach such a conclusion.

There’s consensus that (whichever) Lord of Warrington was done away with, 13th or 15th, the murderer was a Stanley of one sort or another. And version three has some airing on line, i.e. that both victim and perpetrator were brothers-in-law because Lady Butler was the Earl of Derby’s sister.

But then the glitches present themselves. To begin with, in which year was the unfortunate Butler killed? 1463, 1495 or even 1521? And which Lord of Warrington was done in? The video link in the church reference below is definite that it was the 13th Lord of Warrington, whereas Lancashire Folk Tales says it was the 15th.

Next, which Stanley was the aggressor? Some say the 1st Earl, and Lancashire Folk Tales mentions George, but there is another claim—that in 1521 it was Thomas’s grandson Edward, the 3rd Earl (see Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby). But I think we can safely eliminate him because he wasn’t born until circa May 1508/9 and would only have been about eleven/twelve in 1521.

Next, what do we actually know of Margaret Stanley herself? She turns up on everyone else’s page but I haven’t found one of her own. She was born circa 1435 and married three times all told, our Butler of Bewsey being the middle husband. The third husband, who outlived her, was Henry Grey, 4th/7th Baron Codnor (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Grey,4th(7th)_Baron_Grey_of_Codnor).

Margaret didn’t pass away until circa 1481, so before Bosworth/Henry VII, which rather conflicts with versions one and two above.

Now for the tomb in the church of St Elphin in Warrington (said to possess the third tallest spire in England, excluding cathedrals) It is the resting place of the 13th Lord Warrington, who died in 1463, and his wife. There are statues carved around the base of the tomb, but whether or not one is the loyal footman I couldn’t say. If you go to A video tour exploring the history of St Elphin’s Church in Warrington | Great British Life you can see the church and tomb in detail, and hear a commentary all about 13th Lord of Warrington. To add to the puzzle, the occupants of the tomb both died very young in 1463. There is no mention of anyone else being buried with them, such as the brave footman as in version two of the story.

On top of the tomb the 13th Lord holds the hand of his first wife. She was one Isabella Harrington who died in 1441 so can’t possibly have died with him in 1463! Margaret Stanley, as already established, lived on until 1481, so she hadn’t died with him in 1463 either. There was a third wife, Margaret Gerard, but when I tried to find out about her I floundered. It’s conceivable she came between wives one and three and died in 1463, but it’s all very tentative. She certainly wasn’t the first wife.

I don’t know if the tomb identifies the wife beyond her being the first. There may indeed be a name, but then there were two wives named Margaret! Still with me? I hope so, because I began to lose all hope several paragraphs ago! 🙃

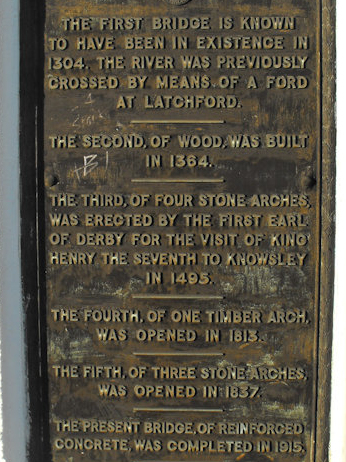

Now to Warrington Bridge. It seems that back in the reign of Richard I, the Lionheart, “….the right to cross [the Mersey] by ford or ferry was granted to Hugh de Boydell. This arrangement remained for two centuries until a bridge was built in 1285 at the location we called Bridge Foot today. Two centuries? Richard I reigned from 1189 to 1199, so a bridge of 1285 was one century later, not two. Anyway, the rights to this bridge were given to the Boteler [Butler] family, which created friction with the Boydells….” Friction? What a surprise. The Butlers appear to have been rather pugnacious when it came to “their” crossing!

But this makes it clear that the ferry of the Lords of Warrington did not have a monopoly of the crossing. Maybe the monopoly came from traffic that was too wide for the original bridge, but could now negotiate the new bridge? That might indeed ruffle Butler feathers.

If you go down the same mywarrington.org link to the heading Third Bridge, you’ll find “….The third bridge, with four stone arches, was erected by the first Earl of Derby for the visit of King Henry VII to Knowsley in 1495….”

So yes, in 1495 Thomas did erect a bridge for Henry VII to cross over the Mersey at Warrington.

More 1463 confusion ensues here. “….Sir John Butler, who died in 1463, is said to have been the victim of an outrage instigated by Sir John Stanley and Sir Piers Legh—a ballad, perhaps contemporary, giving the story of the surprise of Bewsey Hall at midnight by a party of men who crossed the moat in a boat of a bull’s hide, the murder of the chamberlain, and then of Sir John Butler himself. (fn. 32)….”

“….32. The ballad, edited by Dr. Robson, is printed in Lords of Warr. ii, 321–3, where will be found a discussion of the various and conflicting traditions. Mr. Beaumont thought that Sir John’s father, Sir John Butler, who died about 1432, might have been the victim….”

I can only find Volume I of The Annals of the Lords of Warrington (see here https://archive.org/details/annalslordswarr01beamgoog/page/n326/mode/2up), which finishes with the reign of Henry VI. So who’s this Sir John Stanley who was around in 1463? The only one I can think of was the younger brother bullied by Thomas and William. But I don’t know anything about him except that he was apparently the ancestor of the Barons Stanley of Alderley.

Unfortunately for history, the only guilty Stanley to meet his just deserts was William. Rather richly, considering Henry VII owed his throne to Stanley treason, on 16 February 1495 that king had William executed for repeating the crime, this time swinging back to Henry’s enemy, the House of York. It seems William had begun to believe in the Yorkist claims of Perkin Warbeck and when caught paid the ultimate price for such duplicity. He died only a few months before Henry’s June/July 1495 progress of Lancashire!

That’s surely a little too recent for Thomas’s comfort. So I can imagine he was rather twitchy during the royal visit. Might constantly suspicious Henry suspect him of dabbling in William’s treachery? Might his own arrest be imminent? No wonder he was so willing to lavish cash on Knowsley and Warrington Bridge, he was desperate to have the visit go off smoothly.

But this time Thomas had been a sensible little Stanley and stayed firmly in Henry’s camp. He finally knew which side his bread was buttered. It’s hard to imagine how he felt when greeting the stepson who had just executed William. Anyway, Thomas survived to die in his bed in 1504, a year after his son George. Both were eventually succeeded by George’s son, another Thomas Stanley, who became the 2nd Earl Thomas STANLEY (2° E. Derby) (tudorplace.com.ar).

So there you have it. I think version three is probably the correct one, but one thing’s clear—no one should ever have trusted those 15th-century Stanleys, unless a goodly supply of garlic cloves was to hand, together with a wealth of protective good luck charms. Oh, and a clutch of supplications and gifts for favourite saints would probably have helped too.

Happy Hallowe’en, my friends.

Leave a reply to dorahak Cancel reply