“For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

—Antarctic explorer Sir Raymond Priestly

For those new to Shackleton, it might seem counterintuitive to celebrate the leader of a failed expedition; indeed, the names of Scott and Amundsen tend to be more familiar to those who have not yet dipped their toes into the sea of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. This was a time, beginning in the closing years of the nineteenth century, in which focus on the southern continent for scientific and geographical exploration was at its peak. This focus was international, with just under twenty major expeditions from ten countries, and covered a wide range of disciplines. Roald Amundsen’s party was the first to reach the South Pole, in 1911; Robert Scott’s expedition was just thirty-four days behind them.

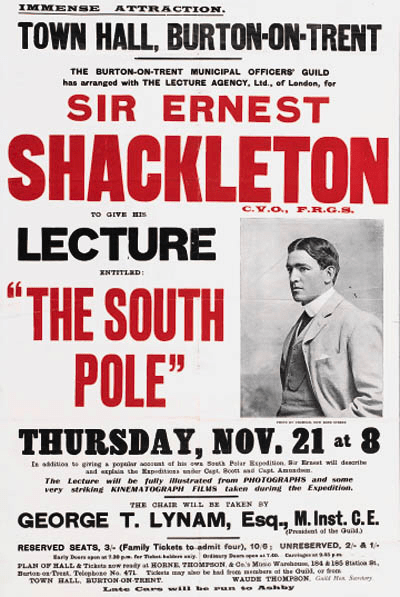

Shackleton had sailed with Scott before, from 1901-1904, on the Discovery expedition, and from 1907-1909 he led the Nimrod, setting the record then for largest advance to the pole – just ninety-seven geographical miles away – in exploration history. His party also completed the first ascent of Mount Erebus, the highest active volcano in Antarctica, located on Ross Island. He was promoted to Commander of the Royal Victorian Order; honored by the Royal Geographical Society, whose gold medal award for him was larger than the one previously forged for Captain Scott; recipient of a clasp to his earlier medal (in conjunction with his party’s silver Polar Medals); and appointed a Younger Brother of Trinity House, a Royal Charter Corporation, pilotage authority, and provider of navigational aids and maritime communication systems, established in 1514. His pathway to this moment covered the four corners of the earth and was birthed in his voracious childhood reading habits as well as a restlessness at school that first brought him to the sea at age sixteen. He had become acquainted and formed alliances with people from all walks of life, and by the time he was knighted in 1909, he not only had great seafaring experience, but also the opportunity to study human nature from many vantage points. He remained restless, however, and threw himself into the lecture circuit and a series of business ventures.

While the lectures brought in some much-needed cash, for the public hero was deeply in debt to his backers, the businesses all failed. However, Shackleton was accustomed to changing circumstances and had been raised on his family’s motto, Fortitudine Vincimus – “by endurance we conquer.” An Anglo-Irish, he had grown up witnessing the changing circumstances of his own family as well as society around him. A failed rebellion against the British, a few years before Ernest’s birth in 1874, was followed in 1879 by years of agrarian agitation triggered in part by absentee landlords’ enjoyment of absolute property rights at odds with the Irish custom of tenant interest, all of which came on the heels of the Famine. Shackleton’s father, Henry, unable to join the British army owing to health reasons, had settled down to be a farmer, but in 1882 moved the family from County Kildare to Dublin to attend medical school. Two years into Henry’s program, the British Chief Secretary for Ireland was assassinated only hours after taking his oath. Upon his graduation in 1884, Henry Shackleton sought medical opportunity in London and young Ernest was educated by a governess and prep school until entering Dulwich College at age thirteen. Despite all these changes and move to England at a young age, Shackleton remained consistent with one thing: he often spoke proudly of his Irish roots.

Shackleton’s accomplished roots include the establishment of a highly successful Quaker school by his ancestor, Abraham Shackleton, in 1726, not long before James Cook’s expedition crossed the Antarctic Circle, the first to do so in recorded history. Here Cook also discovered that the presumed landmass covering the entire Southern Hemisphere, Terra Australis, did not exist, at least not in the size previously presumed, and too far south, he asserted, to be habitable or of any economic value. He dismissed the notion and any contemplation of exploration even if it was out there, writing off literal ages of knowledge originating with the Greeks, whose value of symmetry led Aristotle to reason that the Arktos – the Bear – which they knew about, must surely have its opposite, an “anti-Arktos,” the Antarctic, to balance the sphere of the world. Nevertheless, with Cook’s pronouncement of futility, the flow of funding for Antarctic exploration suddenly ceased.

But centuries of inspiration, while run aground, would not be so easily dismissed. In 1820, a Russian naval officer, Fabian von Bellinghausen, became the first to set eyes on Antarctica proper, disproving Cook’s assertion that Antarctica was likely a fantasy. A year later an American sealer and explorer, Captain John Davis, recorded having set foot on the continent. No more would maps of the world include a southern landmass labeled Terra Australis Incognita with the accompanying understanding that this was just an imaginary land: maybe it existed, but probably not. Its reality was now proven fact.

It’s not likely Shackleton ever contemplated, as some do, that he was born in the wrong period, given his passion for exploration and the sea. Others had hypothesized that a southern continent existed; it was first visualized and proven long before he was born; Davis – and a Norwegian group with their first undisputed claim in 1895 – set his feet on Antarctic soil, or ice as the case would be. None of these milestones achieved by others dampened his own enthusiasm. Not even Amundsen’s achievement slowed him down: he set his eyes on a new object and kept them there. In 1914 his goal became an intercontinental crossing. While not a new idea – one explorer fell short in financial backing and another’s expedition ended in failure – it was there, open and as inviting as the sea lane leading to the Southern continent.

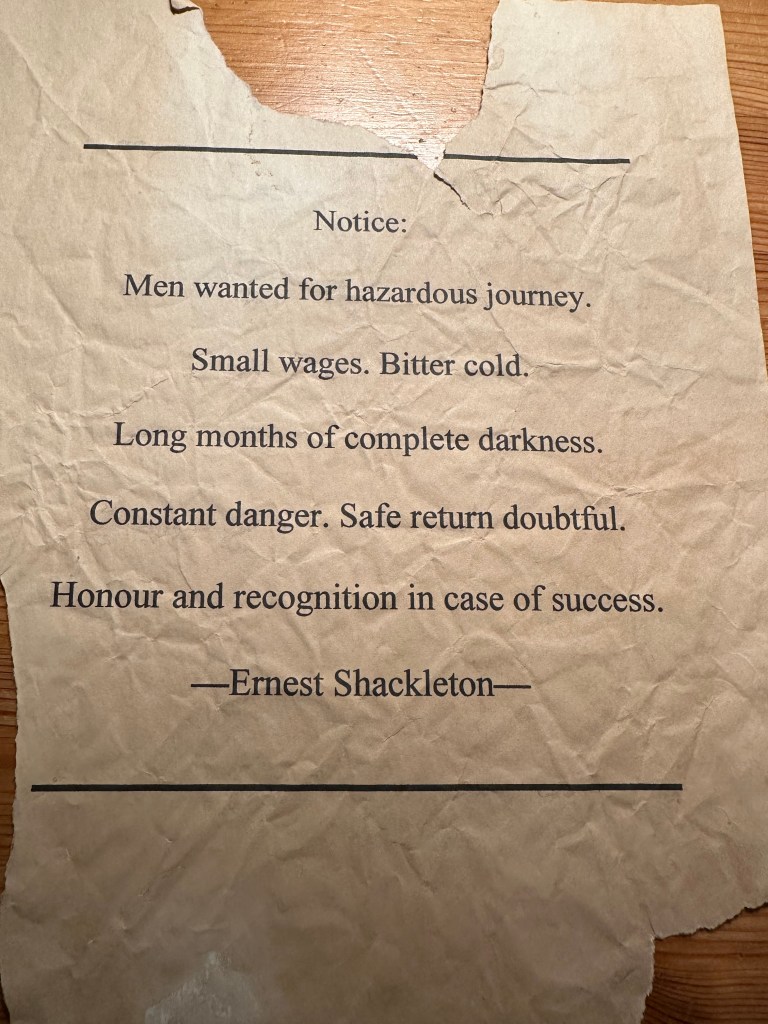

With a crew fabled to have been drawn from those answering this ad~

~ Shackleton organized the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, and Endurance, whose name comes from his family motto, sailed on August 8, on the direction of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, less than a week after the outbreak of the Great War. “The Boss,” as he was known, was a different kind of leader, forgoing the segregation of the ship’s company, and assigning manual labor chores, such as scrubbing floors, to officers and scientists as well as seamen. Even Shackleton got down on his hands and knees. Still, Thomas Orde-Lees, ship storekeeper, loathed the task. “I am able to put aside pride of caste in most things,” he wrote in his diary, “but I must say that I think scrubbing floors is not fair work for people who have been brought up in refinement.” But Shackleton eschewed any sort of favoritism, and perceived idleness as a toxin. Conversely, he saw each crew member as important with something to contribute, and he had seaman help take scientific readings. All work was shared by all personnel, who were kept from cliques by the Boss’s insistence upon rotating shared quarters.

But his primary concern was the well-being of his men and keeping them unified, which in the end became a matter of life and death.

Having related all of the above thus far, it should be added that Shackleton, while a talented fundraiser and with a gift of reading men, was in a number of ways like any man. Polar expedition offered opportunities of scientific advancement and the ability to help create a better world, and it fed the restlessness and instinctive daring for adventure of men alien to life on shore. But it also beckoned with wispy promises of fame and fortune, and Shackleton was not exempt from this allure. He wanted it badly. His ego, however, took a very firm back seat to safety, and the promise of “just one more mile” was flung and very quickly left behind when it came to the value of life. Documentation records instances such as when he gave a biscuit, his only ration for the day, to a starving man, and his mittens on another occasion. At the close of the 1907-1909 Nimrod expedition, he and his crew, bitterly cold and running low on food, turned back short of their overland goal.

They were just ninety-seven miles from the South Pole.

Following his return, his wife asked him why he turned back. “I thought you would prefer,” he responded, “a living mule to a dead lion.”

Aboard the Endurance, danger was always afoot, even when not obviously displaying itself, whether it be manifested in Orde-Lees’ selfish and lazy behavior or in quiet complacency. They had entered a region whose stunning and unbelievable beauty captivated while presenting what was amongst the harshest and most unforgiving conditions on the planet. They were far from civilization and had none of today’s communications apparatus. They were essentially in another world.

It was in the retelling of his story, titled simply, Shackleton, in which I first got a glimpse of what this world might look like, and even on a television screen I could see why the southern region might mesmerize. I had imagined that upon crossing the circle, one might begin to see large ice floes dotting the ocean, with forward progression resulting in more and more of the bobbing ice. The reality, however, is that it stands together, massive amounts of it acting as a guard to the region and distant landmass. There simply is nothing there until suddenly there is. Moving through the pack formations requires a steady hand and an obsessively vigilant eye, as can be seen in this clip from the film. Not unlike what we saw in another maritime movie retelling, Titanic – the historic event having occurred just two years before Endurance set sail – port or starboard had to be navigated along with the bow, and speed was related to how much coal was being moved. At first, Shackleton wished to conserve fuel and ordered a slower pace. He quickly realized, however, that getting past the packs would require speed, running the risk of fuel shortfall. Still, there was delight in the ramming of the ice, as ship photographer, Frank Hurley, recorded: “We admire our sturdy little ship, which seems to take a delight herself in combating our common enemy, shattering the floes in grand style. When the ship comes in impact with the ice, she stops, dead, shivering from truck to kelson; then almost immediately a long crack starts from our bows, into which we steam, and, like a wedge slowly force the crack sufficiently to enable a passage to be made.”

This and other delights were soon eclipsed by incoming movement of new ice that packed harder against the hull, which no speed could push past. Before too long, Endurance ground to a halt and was wedged tightly in a sea of ice. It was January 1915, a little longer than one month since departing Grytviken on South Georgia Island, and summer would soon be drawing to a close. Over the subsequent weeks and months, the men lived aboard ship, going outside on the floe to play games of football, slam at the ice with growing futility, and watch as the wind carried them farther from land and their destination under 100 miles in the distance.

Shackleton re-assigned sleeping quarters and clothing distribution for maximum warmth in temperatures that ranged from +11° to -25°, and routines were switched as he converted the ship to a winter station, understanding they would be trapped until the following spring (September), when they might be released from the ice. But he knew release would just be the beginning of the end. By October, the loosening of the ice caused massive amounts of water to flood Endurance, making abandonment inevitable. The men repaired to the floe with as many supplies as they could salvage. Endurance was being claimed by the Weddell Sea.

“The wind howled in the rigging and I couldn’t help thinking it was making just the sort of sound that you would expect a human being to utter if he were in fear of being murdered. ‘The ship can’t live in this, Skipper,’ Shackleton said at length, pausing in his restless march up and down the small cabin. ‘You had better make up your mind that it is only a matter of time. It may be a few months, and it may be only a question of weeks, or even days… but what the ice gets, the ice keeps.’ I admired his self-control.”

— Frank Worsley, Captain of Endurance, in a meeting with Frank Wild, second in command, and Shackleton, in the Boss’s cabin

Thus, Shackleton’s focus, always on guard duty, shifted, as did his goal. The ship was gone, there was no more to be said about it, only regarding what there was to do now. Initially a plan to remain on the floe was instituted in the hope it would carry them to a nearby island and supplies. A dangerous gambit, the men set out on rescue boats salvaged from the ship, their first night at sea stopping to sleep on a 200′ x 100’ ice floe. The swell caused it to rock visibly and Shackleton was uneasy all evening. As he strolled the floe close to midnight, “I was passing the men’s tent [and] the floe lifted on the crest of a swell and cracked right under my feet.” The crack continued on as Shackleton watched, running beneath the tent and dumping two men into the water between the now separated portions of the floe. One man managed to pull himself back up, while Shackleton seized the other’s sleeping bag and wrenched it upward just before the ice floe slammed shut once more.

There was no more sleep that night.

Soon the men found a small patch of land called Elephant Island, knowing, however, that it could only be a brief stop. The island was small and rocky, populated only by seals they could eat and situated far from any shipping lanes. Already several men were on the sick list, the clothes of many were drenched, they were running out of blubber and flour, everyone was exhausted, and it was here that Shackleton suffered frostbitten fingers after giving his mittens to Hurley, whose own had been lost during the boat journey.

It was not long before the Boss devised a plan to get all of them off the island and back to Grytviken. It involved a 22.5’ boat, 600 miles of sea journey and, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, a hurricane in an area known for its furious westerly winds and three-day hike under murderous circumstances. It was simply mad, but they could not continue to sit on Elephant Island and wait for a rescue that would never come. The world outside was embroiled in a senseless war and, nearly a year and a half since their departure, probably presumed them lost. If they wanted out, it was up to them.

Once more, Shackleton shifted his sights. He had seen drastic, horrific, and extreme changes since childhood, been subject to conditions under which he had little to no control. His father too had borne this witness, and Shackleton had learned well the difference a change of focus might make. His plan had this new object of attention built into it, looking backward entirely scraped away, for it would accomplish nothing, especially nothing to do with the most important goal now: saving the lives of every single one of his men. Every. Single. One. That is simply how it had to be.

As if the feats Shackleton had accomplished thus far in this expedition weren’t astounding enough, not least of them the decisions he made based on his readings of the men, the next portion was destined to make its mark upon history as one of the greatest small-boat journeys ever completed. It would not unfold exactly how Shackleton had hoped, but its story is sheer magnificence, a tale of endurance under conditions very few people who have ever lived have experienced. Some who have experienced similar died doing it. But Shackleton had his focus, and he was moving forward.

Ship carpenter Harry McNish was asked to modify the James Caird, the above-mentioned small boat that had been named for one of Shackleton’s financial backers, to make it more seaworthy. Sealing his final efforts with seal blood, McNish added ballast to help the boat to avoid capsizing. Worsley recorded his thoughts: “We knew it would be the hardest thing we had ever undertaken, for the Antarctic winter had set in [it was now May], and we were about to cross one of the worst seas in the world.”

A detail that stayed with me after watching Shackleton’s Antarctic Adventure, a documentary that features some of Hurley’s own footage, was Worsley’s role in navigating the James Caird. In a tiny boat rocked by hurricane-force winds, rain lashing down on his face and body, hyper-aware of the constant bailing and ice-shipping duty being carried out by the other men, deprived of sleep, and surrounded by an ocean of water he could not utilize to slake his thirst, the skipper managed to stand still as demanded by the use of a sextant, to figure out where they were going.

It’s been quite a long time since I understood how to use a sextant, but I believe I can accurately say this: using a sextant determines your latitude when you measure the angle between two objects, such as the horizon and the sun at its highest peak. From there you consult a table in which you look for the date to then inform you, or in this case, Worsley, how many miles he is from his destination of South Georgia, a whaling station from where a rescue operation can be initiated. The concept, once you get used to it, is not really so difficult; the tricky part is that if you are off in your angle by even one centimeter – if I recall the numbers I’d once read correctly – that makes you off by about 600 miles. My memory could be faulty, but the mileage is huge in relation to the angle measurement; a small error could take you off course by hundreds of miles. So I very quickly had so much awe, admiration, and respect for Worsley’s ability to achieve this under the conditions in which he was working.

Amazingly, this 800-mile journey under the conditions recorded above met with an initial success – except the James Caird landed on the King Haakon Bay side of the island. The men had to either sail to the other side or climb the mountains and glaciers on the island that separated them from Stromness on the other side. Owing to the winds that would surely decimate their boat, they opted for the hike, unaware that a 500-ton steamer had wrecked in the same hurricane they had just sailed through.

As part of the 2002 production for Shackleton’s Antarctic Adventure, producers brought in three of the world’s most accomplished mountain climbers to attempt hiking the same trail as Shackleton, Worsley and Crean (Second Officer for the Endurance). They were kitted with the best modern equipment, navigational systems, contact with others, medical personnel, food and drink – and marveled at how Shackleton’s team managed to do it when they themselves found the climb grueling even under and with their favorable conditions and supplies. The three men from the Caird had nails in their boots, a carpenter’s adze, rope, and desperate drive to get them across the saw-tooth mountains and glaciers filled with arduous passages and hidden crevasses. At one point they needed to reach the bottom of a valley before nightfall and decided to slide down using the rope. The thirty-six-hour journey on trenched feet came mercifully close to completion when they reached a point close enough to Stromness that they could hear the 07:00 whistle. When they made their way down to the station, they told their tale to the station manager who, along with some other whalers, wept upon learning the identities of the men.

*********

The excruciating tale of Shackleton’s adventure doesn’t end here, for it took some time and several attempts to reach the men on Elephant Island. Following the three men’s arrival at Stromness in May (1916), rescuers finally reached the island on August 30. As they approached on their fourth try, Shackleton counted frantically. Worsley recalled, “Shackleton peered with almost painful intensity through his binoculars. At last he sighted the men and counted them. He shouted to me, ‘They’re all there, Skipper!’ Shackleton’s face showed more emotion than I’d ever seen before.”

It was an adventure that defies such a simple word. The unthinkable, the unsurvivable, and yet they did it, they all survived. Every. Single. One. It had been Shackleton’s solitary aim – to get every man home safely, and he accomplished it. Modern business schools now teach Shackleton’s management models in an aim to forge leaders who will do more than just manage, a difference Shackleton accomplished and used to save all his men. “Examining Shackleton’s methods can teach you five key lessons a leader needs to learn to perform effectively,” [Marc] Buelens[, who teaches an international MBA program,] says. “How to bring order and success to a chaotic environment, how to work with limited resources, how to let go of the past, how to embrace troublemakers and how to be self-sacrificing.”

How does one man embody such talents and abilities and be able to constructively utilize them under unimaginable pressure – long before universities were discussing such methods? Perhaps we can only acknowledge that he did it, and that he inspired twenty-seven other men to push themselves to limits far beyond the boundaries of human endurance. Though it was, after all, what he was raised to do. “By endurance we conquer” – indeed he did.

Despite telling Worsley, just before they began their crossing to Stromness, that he would not go on another expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton did embark on one final, with the Quest, in 1922. On January 5, one month before his forty-eighth birthday, Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack and was buried on South Georgia Island. Alexander Macklin, the expedition’s physician, wrote in his diary: “I think this is as ‘the Boss’ would have had it himself, standing lonely in an island far from civilisation, surrounded by stormy tempestuous seas, & in the vicinity of one of his greatest exploits.” Frank Wild, his second in command, rests nearby, and visitors may pay their respects during trips that continue today, though Stromness is closed as a whaling station.

As we move toward 150 years following the birth of Sir Ernest Shackleton, some words from the man himself ~

“At the bottom of the fall we were able to stand again on dry land. The rope could not be recovered. We had flung down the adze from the top of the fall and also the logbook and the cooker wrapped in one of our blouses. That was all, except our wet clothes, that we brought out of the Antarctic, which we had entered a year and a half before with well-found ship, full equipment, and high hopes. That was all of tangible things; but in memories we were rich. We had pierced the veneer of outside things. We had ‘suffered, starved and triumphed, groveled down yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the whole. We had seen God in His splendours, heard the text that Nature renders.’ We had reached the naked soul of man.”

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy Wikimedia Commons

**Stay tuned for more about the 2022 discovery of Endurance**

Leave a comment