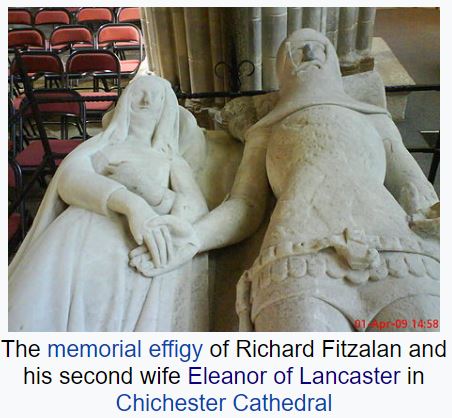

Well, I thought I’d sussed a “tradition” for the illegitimate offspring of medieval noblemen to be named after their father’s title, not given his surname. The family surname was reserved for legitimate children only. Think of Sir Edmund Arundel, who ceased to be Sir Edmund Fitzalan (and heir to a great earldom) when his father, the 3rd Earl of Arundel, discarded Edmund’s mother (Isabel Despenser) and children in order to marry his mistress, Eleanor of Lancaster. The charming earl then proceeded to see to it that the children of his second marriage succeeded to the title, etc. Naturally enough, Sir Edmund wasn’t best pleased, and fought all he could for this great injustice to be righted. To no avail. Arundel he was and Arundel he remained, along with the ignominy of being illegitimate. The earl was laid to rest hand-in-hand with his second wife in Chichester Cathedral.

So this surname/title tradition for illegitimate children seemed further confirmed when I came upon William Huntingdon, who was the illegitimate son of John Holand, 1st Earl of Huntingdon. William, who was at St James Garlickhythe in the city of London for fifty years, becoming master, did not become William Holand.

Right, sorted. No! Not sorted. This morning it suddenly dawned on me that I had a glaring exception in front of me. Sir Thomas Mortimer, a thorn in Richard II’s side, is generally considered to be the illegitimate son of Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March (see above). But Thomas was always a Mortimer, brought up in the family as if he were a full brother of the earl’s other children. So…was Thomas really illegitimate? Was he even the son of the earl? Or was there another Mortimer male to whom he could have been born legitimately?

Or am I entirely wrong about this surname/title thing?

Leave a comment