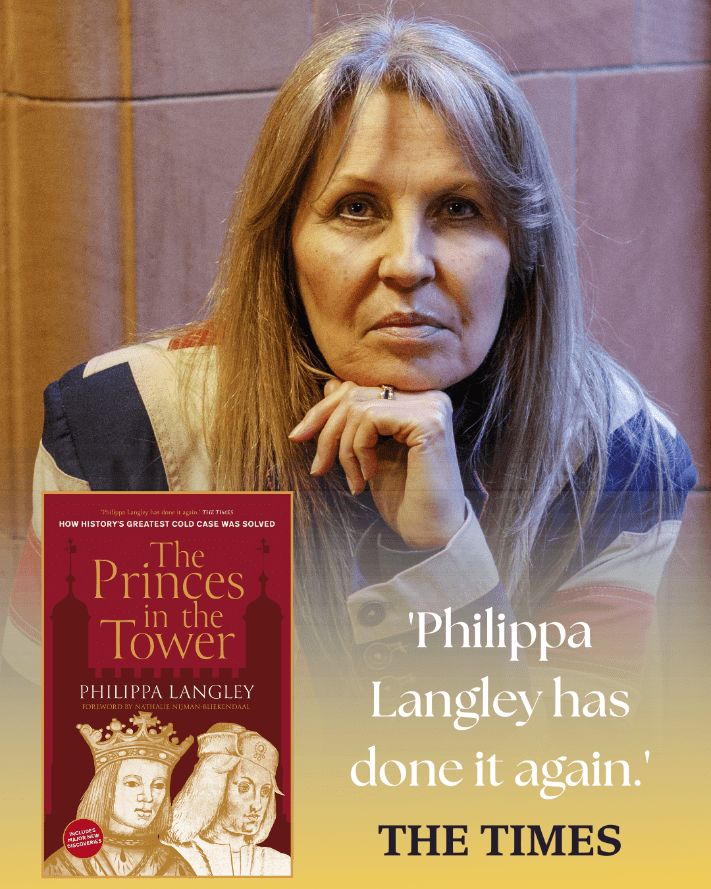

Here is the third in our series of interviews with notable people associated with King Richard III. Philippa Langley is an historian, author, award-winning producer and Ricardian, who is best known for her discovery of Richard III in 2012 through her original Looking For Richard Project, for which she was awarded an MBE.

Joanne Larner: Please tell us a little bit about your background and the very first time you encountered Richard III.

Philippa Langley: Well, I didn’t go to university – I made the deliberate decision not to, and that was because my older brother and sister lived in total poverty because they went to university. I couldn’t cope with that, so I went into the world of work. My career was in Advertising and Marketing but then I fell seriously ill. I got Beijing ’flu and ME – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. And it was, strangely, at this time and just before I got ill that I first read about Richard III, on a beach in Cyprus. I’d gone there on holiday, I wanted a book to read and I picked up this paperback on Richard III, and I thought: ‘Oh yeah, that’s that pretty evil guy from Shakespeare’s Richard III’. So that’s who I thought I’d be reading about, but I’d picked up Paul Murray Kendall’s biography, and he looks at the contemporary sources from Richard’s lifetime and speaks about a very different kind of man. So that really intrigued me, because I thought: ‘Why do we always tell the Shakespearean/Tudor narrative of this man, not the actual man from the sources from his lifetime?’

So, when I fell ill, I had to find a job that wasn’t 9 to 5, which I couldn’t do any more, so I started training and working as a screenwriter and Richard III’s story was one of the stories that I wanted to tell, either on the big or small screen.

JL: So, what did you think of him before you became a Ricardian?

PL: Before I read Paul Murray Kendall’s book in 1993 on the beach in Cyprus, I had never studied Richard or the Wars of The Roses at school. I think I moved house and school and it just fell through the net, so I really thought Shakespeare’s Richard III – Laurence Olivier – was who I would be reading about.

JL: Do you think an element of fate was involved in you becoming involved with Richard III?

PL: Yes, and I’ll tell you why. When I left for my holiday in Cyprus in 1993, I was being interviewed for my dream job. Edinburgh, at the time, had some of the leading advertising agencies in the world. I was being interviewed for two of these agencies and one of them was saying I was pretty much in line for this job, to go away on holiday and come back for the final interview – job done. I was an Account Executive. So I went to Cyprus, read the book about Richard III, thought: ‘That’s really interesting, why don’t people tell that story?’.

On the plane back, I got Beijing ’flu, was seriously ill, in bed for literally over a week, I was exhausted. I then developed ME. I couldn’t take up my dream job, I was too exhausted. So I lost that, I lost the 9 to 5 job too, and my world was imploding. At the time I thought: ‘This is the worst thing that’s ever happened to me and I’m never going to bounce back from this.’ Of course, now, looking back, it was a right-hand turn in my life and it was probably the best thing that ever happened to me, because it completely changed my world.

JL: What is it about his story that struck a chord with you? Why do you think it is that so many are so passionate about him and about trying to restore his reputation?

PL: I think it’s the complete contradiction between the Tudor, Thomas More, Shakespearean Richard III and the man from the contemporary records created during his lifetime. The man of good reputation both at home and abroad. The man who saw the ordinary person in the street, who helped the ordinary people, who wanted justice for them. Who helped the poor, the weak, the disadvantaged, the disabled, the mentally disadvantaged, all the people in society who, as a royal duke and as a king, should not have been on his radar, and yet they were. So he was quite an extraordinary individual. And I think it’s that dichotomy that I don’t understand. Why is it that all the films we see about Richard (except The White Queen, which tried to show a different kind of Richard) are always Shakespeare? They roll out Shakespeare again and again and again. It’s time for the historical Richard to be seen on the screen, based on the sources from his own lifetime.

JL: Do you have someone in mind who you’d like to play Richard?

PL: I have, a really talented actor, but I can’t say who. There is someone who I think would be perfect. (Philippa added that it isn’t Richard Armitage, before you jump to conclusions, as he’s confirmed that he’s too old for it now – JL).

JL: Some have suggested that Ricardians were Yorkists or in some way involved with Richard III in a previous life – what do you think of this theory?

PL: It’s a really interesting one, and I’m gong to tell you what a scientist said to me after a talk I’d given, several years ago, about the ‘Looking For Richard Project’. I spoke about the intuition that I’d had that I was walking on his grave in the northern end of the car park and the letter ‘R’ and all of that.

This scientist approached me and said: ‘Do you mind if I tell you something? I’m a scientist and we’re investigating DNA. Have you had your ancestry investigated?’ I said I didn’t really know where I came from, apart from my DNA sequence which had been done at the dig. And he said: ‘What it seems we are seeing, is that DNA may have the capacity for memory. And if somebody is involved in a traumatic event, it can imprint on the DNA.’ He asked if I had any idea whether one of my ancestors had fought at Bosworth, and I said I didn’t. He thought it was possible that one of my ancestors was at Bosworth, fought for Richard, but, crucially, they survived. They had to survive for it to imprint and come out in a later generation. He said they see this kind of thing quite often, but it’s in the very early stages of investigation, a working hypothesis. So, I don’t know, but that’s what a scientist said to me, so maybe science will one day answer that question.

JL: What first inspired your idea to try to find Richard’s remains?

PL: It was that intuition in that car park. Walking into the northern end of it and just feeling I was walking on his grave. That changed my research focus, because I had been looking into his life. His life is what fascinated me, because I was writing his story for a limited TV series, but that changed my research focus almost overnight, to his death and his burial.

JL: When the curved spine was revealed, what were your initial thoughts?

PL: I was totally shocked, because all the research I’d done showed that those who met Richard, who knew him, wrote about him or described him, during his lifetime, mentioned nothing abnormal. A couple of accounts said he was short of stature, but that’s it. So this completely floored me, because I’d also spoken to medieval combat specialists and equitation specialists, specialists in horse riding, and they all said that if he had kyphosis, he wouldn’t have been able to do all the things that we know he did, from the historic records. Kyphosis is the forward bend of the spine where the head is pushed forwards and onto the chest, for which we have the inappropriate term from Shakespeare that we don’t use now, of ‘hunchback’.

So, when the expert at the dig said: ‘These remains look like those of a hunchback’, I could see with my own eyes the curve in the spine, that he was hunched in the grave with his head up and on his chest. I think, as you can see in the documentary, I was knocked completely sideways by it. But, once they got him into the laboratory, and they said: ‘No, it’s not kyphosis, it’s a scoliosis, but it looks like his grave was cut too short, hence why he was hunched in the grave – those that dug the grave thought he was shorter than he actually was,’ that explained it.

But we then had to run the full gamut of ‘Richard, the Hunchback’ for a long time, because Shakespeare loomed so large back then. I learned years later, that a member of the TV crew had even persuaded the scoliosis specialist at the documentary to call the remains hunchbacked, when he’d said you don’t call someone with scoliosis that. In fact, it’s really inappropriate to call somebody with kyphosis that. But yet, because of Shakespeare and because of the traditions about Richard III, which were so powerful and ingrained, he said it, and he said it on camera. And I think you can see my reaction. I just thought, because we knew by then he had a scoliosis: ‘People are not interested in the truth, they’re just interested in the old stories and the tropes about him.’

JL: How did you feel when it was confirmed that the remains were those of Richard III?

PL: That was a huge moment. I was elated, because the Looking For Richard Project was a retrieval and reburial project, and that was just the first part of it – to retrieve and identify him. The really important part of the project was the reburial, and I now knew we were on our way to rebury a king of England and to rebury him as such, because that was in all my agreements in Leicester and had been conveyed to the royal households and burial authorities such as the Ministry of Justice.

JL: What were the main challenges you faced in your attempt to find the lost king? How did you overcome them?

PL: I think the biggest challenges were the exhumation stories. When you read the history books published before 2012, they state that Richard was exhumed and his stone coffin became a horse trough, or he was exhumed and his remains were thrown in the nearby river. This was because Richard was so evil that people just wanted to dig him up and get rid of him. When I was in Leicester trying to pitch the project, there was a lot of eye rolling and people patronising me, saying: ‘Doesn’t this woman know that he’s not there?’

But I just had to push through that, the research looked good, not only for Richard’s grave still being in situ, but for it being in the northern end of the Social Services car park. I just had to be determined, walk around them and ignore them. This was in 2010-13, before #metoo. So, as a woman I got a lot of that, but I think particularly because I wasn’t an academic and because I was a Ricardian, and even, in some cases, because I was from the north. So, in four aspects, I was getting hammered.

JL: Your search was dramatised in the film The Lost King – what do you say to people who claim it is not factual?

PL: Just read the two books that were published, by myself and by the Looking For Richard team. Read the books – it’s all in there, complete with published documents and numerous evidences.

JL: How have your experiences on the Looking For Richard Project changed you?

PL: They’ve changed me a lot. I think I was very trusting then and if somebody with a very important name, or initials after their name said something, I never questioned it, even though I was the Richard III specialist at the table. I thought they must know more than I did. But now I don’t – I question, question, question and I’ll pull up anybody, in terms of what they say about Richard, if it’s not historically accurate.

JL: What is your answer to those who say you are just in it for the fame and making money?

PL: I’m in it because it’s about finding the truth, whatever the truth is, that’s what’s important to me. It’s always been what’s important to me. And for those who say: ‘You’re in it for the money,’ I think they’ve never published a history book. History books don’t make money. I’m sorry, but they don’t. I’m not a Philippa Gregory or a Hilary Mantel, I publish books about research projects, about the search for truth.

JL: Your new research on The Missing Princes Project indicates that Richard’s nephews, Edward V and Richard of York, survived his reign. Can you share the most convincing pieces of evidence you found?

PL: There’s so much. I think the proofs of life we found initially, namely an accounting receipt in the Lille archive, in Northern France for the elder boy, Edward V, that is really important for him and a definite proof of life, and the Gelderland archive for the younger prince, Richard Duke of York – this is his ten-year story, written in the first person: ‘I, Richard’ and it’s remarkable for its detail. There are numerous other things that have just been published, thanks to a key researcher into the younger prince, Nathalie Nijman-Bliekendaal. Nathalie has uncovered a treasure trove of materials in the Nuremberg archive in Germany. Previously, there was an item she’d uncovered in Dresden, in Germany, which we thought was the only surviving original seal for the younger prince, the Royal Seal of England – Nathalie has now discovered four more. We also have numerous documents with his signature, and Royal sign manual. And one which is currently unique, which has the Prince of Wales feathers on it, denoting the heir to the English throne. We also have a contemporary chronicle revealing the young prince was expelled from his kingdom and a letter from James IV of Scotland who confirms the younger prince is the son of King Edward IV.

We’ve also found other things about the elder prince: that he was described as the son of Edward IV, which goes completely against the official story from Henry VII and his government that he was an imposter for Edward, Earl of Warwick. These have now all been brought together in one place, in a fully updated Chapter 19 of the new book and a new Chapter 21. Chapter 18 is also fully updated.

One of the most interesting things came from researcher Marie Barnfield, who brought to light that the younger prince had been awarded a Papal grant by the Vatican, in May 1494, as Richard, Duke of York, the son of Edward IV, in his own name. So, I think the totality of evidences we now have, point to their continued lives and the fact there is absolutely no evidence that either of them died during the reign of Richard III, never mind were murdered, there’s nothing.

JL: How do you think these new findings change our understanding of the character of Richard III?

PL: If you know about Richard III from the contemporary sources, if you read about his life as Duke and King, it doesn’t change anything, because you understand: ‘That’s the man we can all see and read about. He didn’t present at any point as a murderer of children.’ It was against his own self-interest, because they were illegitimate. So to be a new king and think: ‘Yeah, let’s murder a couple of children – that’s a really good look for me’ people really don’t think it through and that’s why The Missing Princes Project had to be a police cold case investigation, to bring evidence, facts and logic to the table. Then you just see the man from his lifetime, being the man from his lifetime – it removes the Tudor mud.

JL: What do you say to those who still insist on the traditional narrative?

PL: I would say: ‘Please read the new book. Read it. Because I am challenging you to read it. And once you have read it, go away and then come back and give me the actual evidence that both princes were murdered during the reign of Richard III. And I’m not talking rumour, hearsay or gossip from the Continent, it has to be evidence. And don’t be selective about what you read in my book – read the lot!’

JL: Because the main evidence is backed up by other evidence, isn’t it?

PL: Yes, there is evidence on evidence on evidence, so don’t be selective.

JL: Why do you think they still cling to their beliefs, which now seem to be false?

PL: I understand this, if you’ve been reading your entire life about how Richard murdered the princes in the Tower, or if you’re a writer, commentator, historian, academic, who has written books and papers all saying that Richard murdered the princes in the Tower, I understand they are just going to fly at this and say it means nothing. I get that. But this isn’t about your reputation, it’s about Richard’s. I don’t care about your reputation, I don’t care about my reputation. This is about a man who has been maligned for more than 500 years. And everything that we can see about this man confirms that.

I think it’s probably the young generation of historians coming up now, who will start to really change how we see Richard. I hope the majority of them will have a free voice. There are a small number of powerful institutions in this country that don’t allow their young historians a free voice, because they’ve been in touch with me and told me what happens behind the scenes. Luckily, it’s only a very small handful with a few powerful historians. I think most institutions allow them to fully question without it impacting on their careers. So I hope for the future – I do. I hope they can push through it. Plus, the research continues and more discoveries will be published.

JL: Are there any other historical mysteries or projects you’re currently working on or would like to explore in the future?

PL: Firstly, the bones in the urn in Westminster Abbey. What we know is that there is no historical, archaeological or scientific evidence for these being the remains of the princes in the Tower and I want them looked at now, with all of our modern sciences, because that is another huge myth, like the exhumation stories. The Tudor story is they were buried beneath a stair and then shortly afterwards removed and buried elsewhere. The remains in the urn were actually found ten feet down in the foundation level of a building. This is the level at the Tower for Iron Age, Saxon and Roman remains and very likely represents a foundation burial.

Then, I think certainly Henry I in the car park in Reading. That is, hopefully, in the pipeline shortly. This is an archaeological dig by Reading Borough Council and I’m a part of that because I promised I would help initiate that search project for the abbey and King Henry for the people of Reading and to then film it with a documentary film crew. That’s going to be a really interesting one, to help bring this important abbey back to life.

We’ve agreed that if Henry’s sarcophagus burial is found beneath the car park in Reading prison, then he’ll remain in situ with some form of memorial created above ground, whether it’s a garden or something like that. And also, with any others that are located, such as Constance of York, the great-aunt of Richard III, it would be a real marker to have a memorial garden for her along with Henry I. However, if his sarcophagus burial has been smashed, as may be the case, according to the ground penetrating radar survey that we’ve had done and in an account that we have, then he will be reburied in St James’ Church which is directly adjacent to the burial site and is a Catholic church. Richard, as a Catholic monarch, didn’t get that, but Henry I will.

JL: What advice would you give to amateur historians or researchers who might be inspired by your work to pursue their own historical investigations?

PL: To go for it! Those who question will always make discoveries. So I would definitely say, do your research, do the leg-work and let that speak for itself, And be determined. Don’t let people patronise you, denigrate you, criticise you, put you down or bully you. If you’ve done the work and can support what you say, then go for it.

JL: If you could go back in time to Richard’s lifetime, what advice would you give him or what questions would you ask him?

PL: After the uprising in October 1483, when he discovered that Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry Tudor, was involved in a big way, I would strongly advise Richard to take her into his custody, to send her to one of his secure fortresses in the north, such as Pontefract Castle. Then, to send a message to Henry Tudor: ‘Your mother has committed treason. I am not going to execute her, (because Richard didn’t execute women) but if you invade this country, she will be executed immediately.’

There would then have been no Battle of Bosworth. Many people say that he had to keep friendly with Thomas Stanley (her husband) – he would have, because he wasn’t executing her, just taking her into royal custody to make sure he could control the situation. And Stanley should have been alright with that, he should. He wasn’t one for putting himself in the line of fire. Richard would then have been free to go on the offensive against France and the rebels it held, and invade England’s ancient enemy.

Here is the link to Philippa’s updated version of her book with the new evidence:

https://www.revealingrichardiii.com/solved.html

And the link to Philippa’s story in search of King Richard:

https://www.philippalangley.co.uk/looking-for-richard.html

And the link for Richard’s character from the records created during his lifetime. Philippa’s short talk is available here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3ZOOz-W5FI

With thanks to Philippa for permission to use the photographs

Leave a comment