Murrey and Blue’s second in the ‘An Interview With…’ series is with Dr Toby Capwell, expert on European arms and armour of the medieval and Renaissance periods (roughly, the 12th century to the 16th). He was formerly Curator of Arms and Armour at the Wallace Collection in London.

Joanne Larner: I’ll start by asking how you first came to be interested in armour and the mediaeval period and what was it that attracted you to it?

Toby Capwell: It’s really a child’s fascination that’s gotten completely out of control. I think if you asked most arms and armour specialists or medieval historians that question, it would turn out to be something they loved in childhood that just never went away. It’s like the child who wants to be a fireman – most of those children eventually decide to do something else with their lives; but a few end up as firemen for real. One of my earliest memories is of a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art when I was four or five years old. That’s my earliest memory of knights and armour, and it had a profound effect.

JL: How did you get to be a specialist in this field?

TC: Well, as a child I did everything I could to follow my interest – I started riding horses when I was ten, I studied martial arts and fencing, I had full plate armour by the time I was eighteen, and I was jousting in front of thousands of people at twenty. All of that experience got me a job at the Royal Armouries, training horses and jousting when the museum moved to Leeds in the mid-90s and, once I was working in a museum, I felt this very strong pull towards academic work. I felt this affinity with the original historical objects that I was looking at every day.

I had by this point done my undergraduate work, but I won’t claim to have been an academic genius: I often lacked focus when it came to traditional schoolwork. But once I recognised my mission, I went after it with a vengeance. I did two Masters degrees and a PhD, I was Curator of Arms and Armour at Glasgow Museums by 2003, I joined the Wallace Collection in 2006 and was Curator of Arms and Armour there for sixteen years, all the while writing books and articles and preparing my PhD for publication, which took another twenty years. So, one thing led to another, you might say.

JL: What advice would you give to someone who is interested in pursuing a career in the same field?

TC: Well, my career path is unusual and not exactly repeatable, so I’m not sure it’s helpful to anyone else. I’m reluctant to give advice, but in broader terms, if you’re passionate about something and it gets hold of you, do it however you can, take whatever opportunities are in front of you, follow it with absolute commitment and unwavering dedication. Luck is always very important too; you can’t make luck happen, but you can prepare the conditions for lucky things to occur: you can get out there and meet people, do the best work you can and make sure people know about it. And then, when you do get lucky, you have to take full advantage of it – it’s easy to be lucky and then do nothing. The luck is a magical serendipitous thing, but once it happens, the rest is up to you.

JL: Can you share some interesting or challenging projects you’ve worked on, concerning armour or jousting or anything else?

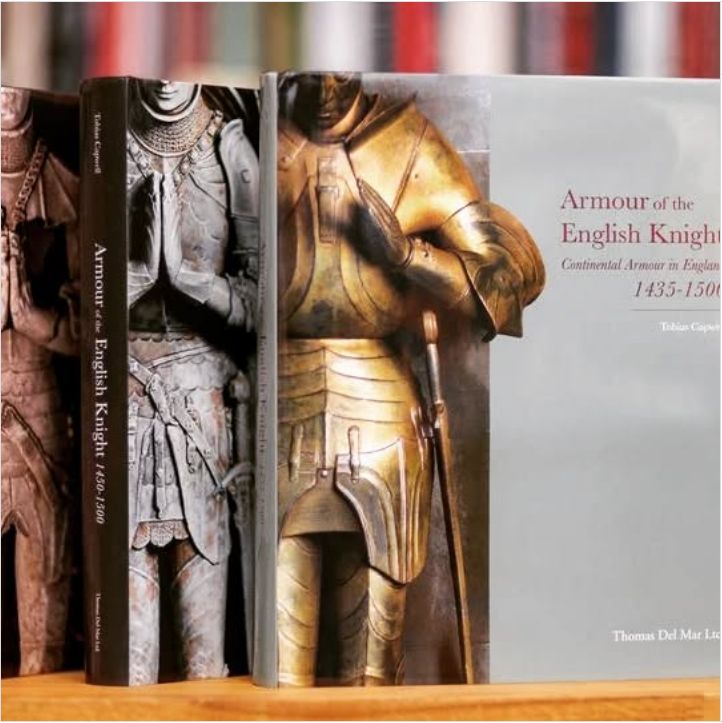

TC: Yes, the work I’m most proud of and what I’m most known for at the moment, is my three-volume work Armour of the English Knight. (See links below for how to get these – JL)

Those publications run to a total of around eleven hundred pages and have thousands of integrated images. It was originally my PhD; I then put years more work into it, in preparation for publication. PhD students are often pressurised to publish their PhDs right away and that’s often not a good idea. I’m relieved that I took the time to work it up a lot further. The PhD was completed in 2004, and then published in the three books in 2015, 2021 and 2022. I’ve also just done a little follow-up book, which is intended as a more accessible, more affordable summary of the project. If you want to know what it’s about, but hundreds of pounds of investment is not where you are with the subject, the new book, Armour of the English Knight: An Armourers’ Album is designed to be that more accessible book, and is coming out in the autumn.

I do have other interests and I’m writing other kinds of things: more academic articles, narrative history, and I’d like to do a children’s book or two at some point. But I think, for Ricardians, Armour of the English Knight is the most directly relevant – the second book is entirely dedicated to the second half of the fifteenth century and the essential thesis looks specifically at armour culture in England, so it’s a fundamental part of understanding the human experience of the Wars of the Roses.

If you don’t understand the material culture, you can get some very weird ideas about what was going on. And I think any Ricardian can empathise with the desire to understand that period in history from the point of view of the human beings who were really there: what was in their minds, what was important to them and what did they believe, what were they trying to achieve, what were they doing physically, and what were they up against? The real understanding of armour, its capabilities and the weapons of the time, is still very mysterious to most people, but if you are going to create your own reconstructed understanding of the period, you’ve got to know the nuts and bolts.

But I’m also really proud of my work on Richard III and just when I think it’s over and I’m doing other things, he comes back. I worked a bit with Philippa Langley on his skeleton, spoke at the 2013 ‘Greyfriars Dig’ conference, and then the Channel 4 programme happened later that same year, then the reburial in Leicester in 2015… then the feature film The Lost King that I worked on as historical advisor in 2021… And maybe he’s not finished with me yet.

JL: What are some common misconceptions about medieval armour or jousting that you’d like to dispel?

TC: We don’t need to talk about jousting because Richard III wasn’t really interested in tournaments. I sometimes wonder whether Richard’s role model as a king, the king whom he really admired and tried to live up to, was Henry V. A lot of different things have made me think that, but notably, Henry V had no interest in tournaments either. There were very few jousts held in his reign, and the one that I can think of, he didn’t participate in. And that’s a real contrast to the kings of the fourteenth century like Edward III and Richard II, who were tournament mad! Their royal courts revolved around jousts and tournaments and chivalric spectacle. So, for Henry V to have broken with that, is really interesting. And Richard III is another one: jousting doesn’t really come into his life; he is a very serious character and real warfare, real business, politics, the questions of rulership, the job of being a leader and military commander – that’s his whole life and he just didn’t have time for tournaments.

As far as misconceptions about armour and knights, well, how long have you got?! The list goes on and on and on. Misconceptions breed misconceptions, and misconceptions quickly pile up in a great heap – they are self-perpetuating. For example, if you believe the misconception that a medieval knight’s armour was unbearably heavy, you might think that with all that heavy armour, what horse could carry that? To carry all that weight, he must have had a giant carthorse, a Clydesdale or Percheron or some other creature of dinosauric proportions. And then you think, well, if the knight in all of this massive, heavy armour has to ride this gigantic monstrous horse, how would he actually get on to it? Obviously, he must have had a mechanical crane to lift him on. It’s all perfectly straightforward, and it sounds weirdly logical, right? Except… your initial assumption was wrong, so the reasoning that followed on from that was misguided from its beginning, and thus your final conclusion ends up being pure fantasy.

Armour is never catastrophically and unbearable heavy – it’s practical fighting equipment that had a real job to do for real human beings, who were wearing it for very good reasons. Their lives depend on it. The maximum weight of a war armour in the fifteenth century was around thirty-five kilos, which is an important cut-off in regard to the capabilities of the human body. Beyond that sort of weight, the load will start to tire you out too fast, and slow you down too much. Actually most armour in the 1400s weighed more like 25-30 kilos. Modern infantrymen in the British Army for example actually tend to carry more than 35 kilos into combat: they have to carry ammunition, radio equipment, grenades, water and ceramic plates – modern ceramic armour is very heavy. So modern soldiers actually have a harder physical job to do than Richard III and the knights of the late Middle Ages. And the medieval warhorse was small: around fifteen hands tall – like an Andalusian or other Classical riding horse today. And how do you get on it? Well, you put one foot in the stirrup and you get on! That is the way of all self-respecting horsemen since the early Middle Ages.

The thing about misconceptions is that they fool you initially, because they sound, superficially at least, weirdly plausible. And it’s easy just to take the answer you are given, accept it, and think no more about it. But if you actually really consider the implications of what the misconception is proposing, and ideally if you examine the real historical evidence for yourself, it falls down very quickly. The actual historical record, which describes knights fighting dynamically and successfully in full plate armour for hundreds of years, clearly reveal that armour was far from clunky, cumbersome and useless.

If you bother to look at the depictions of knights in full plate armour of the 1480s, for example, such as those painted by Hans Memling, one of the great painters of the northern Renaissance, pictorial works that are almost as good as photographs, he shows you fully armoured warriors on little horses, that they can easily step on and off of.

And with the knight and misconceptions, you’re dealing with a duality: there is the knight as a modern, cultural archetype, a figment of modern literature and imagination, and then there is the real knight who lived a real, human life. Those are two different things. Modern conceptions of knighthood: the heavy armour, the being shot to pieces by archers, the giant horses, that is all part of the modern fantasy-model. It’s especially important to recognise that these days we often have this satirical, mocking attitude to knights in armour. This view originates with Cervantes in the 17th century, who, in Don Quixote, invented the idea that you could use the armoured warrior as a satirical device – to stand for a ruling class that’s out of touch, that can’t change with the times, that’s obsolete, that can’t see the world the way it really is. That’s not any real knight, that’s a literary-social construct that appeals to a modern mind that historically, for the last couple of hundred years or so, has been obsessed with class war.

So, the knights of our imagination are symbols of our attitudes to nobility and ancestral aristocracy, and our opposition to that: the rise of the common people, the rise of democracy. We’re the ones obsessed with class war – that’s got nothing to do with people in the fifteenth century and what they were thinking. We have to be clear about what’s in our heads and why. Are we interested in knights as real human beings, who had to obey the same physical laws on the same planet as we do? Or are we interested in our flights of disassociated fantasy?

JL: When did you first become interested in Richard III and at what point did you believe he’d been grossly defamed by history, Shakespeare, etc? Do you believe that?

TC: I wouldn’t say I believe he’s been grossly defamed, I wouldn’t say that, but there is certainly a disconnect between the facts of the real Richard III and the makeup of the literary character refined and immortalised by Shakespeare. Richard III was a knight, and very much like the whole concept of knights in general, his common memory has become similarly detached from reality and distorted.

I think I first encountered Richard III as a child, through Shakespeare – Shakespeare is the way most people meet Richard III, and that’s also why, later in your life, when you first get a whiff of the difference between Shakespeare and real history, you easily become intrigued by the realities of who Richard III might have been as a real person.

I saw a number of productions of Shakespeare’s Richard III as a child, and one that really stands out is a stage production held in Central Park in the 1980s, where Richard was played by a young, up-and-coming actor who wasn’t a star yet, but he was clearly going places…. a young guy named Denzel Washington, and he was marvellous, absolutely marvellous!! One of the essential things about Shakespeare’s Richard III is his tremendous charisma and attractiveness, let’s be honest about that. Yes, he is also a villain, but he has to be seductive. It makes you tingle when you think: ‘Ooh! He’s so evil and I love it!’ And Denzel Washington really brought that out. People in the audience, honestly, were screaming in ecstasy! There were a lot more young women in the audience than maybe ‘Shakespeare in the Park’ usually attracts!

And then there was a National Theatre production in the early 90s with Ciarán Hinds playing Richard III, and that was utterly fabulous as well. I remember also when I was a student in the nineties, I had an armourer friend, Peter Leicht, who was working for the National Theatre, and who actually made Ian McKellan’s fifteenth-century armour for his famous National Theatre production of Richard III, which was later developed into the film that’s set in the 1930s. So, Shakespeare for me, as a child, loomed large.

I did read The Daughter of Time when I was a teenager and I think that was when I had my first sense that maybe there is something else going on here, that maybe the history of Shakespeare is not the end of the story and not really the beginning of the story either. And I developed that sense when I was an undergraduate. I did a course on history and Shakespeare in general, looking at all of the history plays and then comparing them to the real history as far as we know it. That’s an interesting way to look at Henry IV, Henry V, all of them, but obviously Richard III is the centrepiece of that whole discourse, and it’s also a reminder that if you want all of Shakespeare’s Richard III, you have to take Henry VI Part II into account as well, because that’s where Richard of Gloucester murders a lot of the people that he is supposed to have murdered, and that’s really the first half of the story of his literary usurpation.

So that’s really where I came to it and, as a specialist in arms and armour, and a medievalist, the heart of my interest has always been the second half of the fifteenth century, the Wars of the Roses, and Richard III is the personification that whole period. He is one of those remarkable people who stands for his time. He is two and a half years old when the Wars of the Roses began and his whole life WAS the Wars of the Roses. And that’s it – he was there at the beginning and he died at the end. And that goes some way towards explaining the totally unique fascination that he continues to attract.

JL: How did your experience escorting Richard III’s remains to Leicester Cathedral affect you and how did it come about?

TC: Well, it’s a long story and I relate the whole thing in one of my talks, ‘The Scoliotic Knight: Encounters with Richard III’… I periodically give that one live, and just today I’ve put it up online so it’s viewable as one of my online lectures, which is a new programme that I’m just starting. When I mention on social media that I’m speaking here, or there, people online in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, America, or somewhere else distant from the UK, say: ‘Fine, it’s great that you’re speaking in London, but how can we see it?’ So, as I’ve had a lot of requests for my lectures, I’m doing it that way now.

But essentially, I met Philippa Langley in about 2004, when I was Curator of Arms and Armour at Glasgow Museums and she brought the Scottish branch of the Richard III Society round for an arms and armour tour. We got to know each other and I told her about my work on church monuments. My whole PhD is about knightly church monuments and looking at the iconography of the armoured knight, in church sculpture particularly. And that was what moved her to tell me about a project she was starting called ‘Looking for Richard’ – now a very famous initiative which was then in its infancy. And she mentioned this to me because, in investigating Richard III’s burial place in the Greyfriars Church, one of the things you notice quite soon when you look into it, is that Henry Tudor built a funerary monument for Richard III and placed it over his grave. That’s a matter of record. And Philippa thought that if they ever got to do an excavation, they might very well find a fragment of the monument. Her question to me was: how would we recognise it? If we find a bit of an effigy’s foot, how might we say this is Richard III’s monument and not anybody else’s? And what might Richard III’s monument have looked like anyway?

So, this discussion was the beginning of our association. And then, years later, early in 2012, she told me that she’d got it all together, raised all the money, the University was on board and they were going to do an excavation, and she invited me to the grave site, the excavation site – I was there on the day they broke ground, in the famous car park!

And then, periodically, I would get a call from Philippa with a new mission and off we’d go. It was Philippa that brought me into the investigation of the remains, and that led to the second of the Channel 4 documentaries, and that led to us riding in the reburial procession in 2015.

I love Philippa – she’s got this power, charisma and presence… and talk about drive! She’s one of those people who walks into a room and everybody pays attention. And she was like that even before the famous discovery, she’s great. When she calls me, I answer.

JL: How would Richard’s scoliosis have affected his fighting and how would his armour have needed modifying?

TC: That was the subject of the Channel 4 documentary that is still available on You Tube, ‘Richard III: The New Evidence’ (see link below – JL).

This was the follow-up to Philippa’s programme about the excavation (‘The King in the Car Park’). I talk about the mechanics of his armour in a lot of detail in my talk, ‘The Scoliotic Knight’.

But essentially, our conclusion, after working on it for some considerable time, is that his physical capabilities as a knight would not have been unduly affected at all, he indeed could have done everything that he needed to do as a knight and military leader.

There were certain things that would have been harder for him and he would have had to have worked harder than an ordinary person, for example, once the scoliosis became more extreme, especially in his twenties, post- Barnet and Tewkesbury, he would probably have started to have more of a problem with cardiovascular endurance, for the simple reason that there wasn’t any longer enough room inside the right side of his chest for his right lung to inflate, so he would not have been able to take deep enough breaths. He couldn’t get enough air, when his body started to work harder.

But with serious effort, dedication and training I think he surmounted that obstacle, it was just tough. And also, with a spinal curvature of that extremity, your body’s ability to directly resist the influence of gravity is compromised. Imagine your spine like a Greco-Roman pillar running straight up the middle of your body – that’s what keeps you upright, allows you to bear weight, stand tall and sit up straight on your horse.

The human form has evolved that straight brace opposing earth’s gravity, over millions of years, and, if that’s compromised, you have all kinds of problems. People with scoliosis have told me that they feel they are constantly fighting gravity, that it is constantly trying to push them down and they have to work hard to stand up straight, so I think we can infer that that was part of Richard III’s experience as well.

By the time his scoliosis had progressed to the extent it had at the time of Bosworth, Richard could not have worn a standard armour, he just wouldn’t have fit into it – it wasn’t a size issue, it was a shape problem. The normal human body is symmetrical, as is, therefore the volume of space inside a steel armour, which by this period of history is an entire human exoskeleton, a metal skin over the whole body. So if you have a significantly abnormal volumetric demand on one side of your body and very little on the other side, you can’t get into the gear. For the Bosworth campaign certainly, there is no question at all that Richard must have had highly specialised armour made specifically for him, just as we had to make a custom-shaped and fitted armour for Dominic Smee in the Channel 4 programme – Dom was our perfect ‘test pilot’, since he has a severe adolescent onset scoliosis, progressed to the same degree as Richard III’s.

JL: If you had a time machine and went back to just before the Battle of Bosworth, what advice would you give Richard to change the result of the battle, with hindsight?

TC: I would tell him: ‘You’re about to be totally faked out and wrongfooted by the Earl of Oxford – don’t let him fool you into splitting your army.’

It was the Earl of Oxford’s generalship that started to move the battle out of Richard III’s control. Richard had a very good position, he’d gotten there the day before, he’d chosen the ground, he put himself in a place that was a perfect location for his artillery and an ideal launch position for his heavy cavalry, he had this area of marshy ground just south of his position that he used as a natural fortification that protected his artillery and gave his cavalry a protected area to form up before attacking. And then he had a fairly large force of knights, men-at-arms and infantry on foot.

It went wrong for the King in a couple of ways, but the first misfortune came when the Earl of Oxford moved forward very fast, right towards Richard III’s command position, in good order, commanding a large number of men. This was a rapid advance, intended to give Richard III the impression that he was coming straight in. And he was moving so fast that Richard III’s artillery couldn’t follow him – they were blasting away but they hit precisely nothing.

Glenn Foard led the comprehensive archaeological survey of the battlefield – they found gun stones all over the place and none of them ended up where they needed to be to do damage to Henry Tudor’s army. So, Oxford moved very quickly and then, when he got to that area of marshy ground, he suddenly turned left and moved his force rapidly around the west side of the royal formation. And a movement like that, in good order, and with large numbers of men, is not easy. You have to be a really good commander to achieve something like that, with such speed that it really surprises your enemy and they don’t time to deal with it.

So, Richard III immediately sent Norfolk and the majority of his army west, shadowing Oxford on either side the marsh, until they reached dry land and thus were able to engage. But by that point, Norfolk and Oxford were quite far away from Richard III, his cavalry and everybody else, and at that point Bosworth really became two battles, separated by a considerable distance, and you have to remember, nobody’s got radios, mobile phones, drones or anything – they can’t really communicate effectively. Command depends on pre-instruction, for the most part, and once the battle starts, it goes how it goes. If something unexpected happens, everything can fall apart very fast. Nevertheless, Richard III nearly won – by taking his heavy cavalry down there and coming within inches of killing Henry Tudor. So, the other thing I would have said to Richard III is: ‘Go down there, but make sure the standard bearer doesn’t get in your way. Because he’s going to try and get between you and your enemy and, in my reality, you killed Sir William Brandon when you meant to kill Henry Tudor, in the initial collision of the heavy cavalry forces.’

So: ‘Don’t get fooled by Oxford and make sure you kill Henry Tudor as quickly as possible!’

JL: What was it like to teach Danny Dyer how to fight in armour?! (Toby was involved in the BBC’s ‘Danny Dyer’s Right Royal Family’)

TC: Danny Dyer was hilarious – a good sport, although I think fighting in armour was a bit scary for him. I enjoyed hitting him with a pollaxe.

JL: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

TC: If anyone is interested in my work, you can follow me on Instagram, I’m on Facebook, I do live lectures, I do TV, I’m publishing books and articles as fast as I can, I speak for the Richard III Society off and on, and I hope what I’m doing is of interest.

Relevant links:

Armour of the English Knight 1450-1500 (Book 2) can be acquired here:

https://www.olympiaauctions.com/about-us/publications/armour-of-the-english-knight-1450-1500-by-tobias-capwell/

And Book 3, Armour of the English Knight: Continental Armour in England 1435-1500 can be ordered here:

https://www.olympiaauctions.com/about-us/publications/armour-of-the-english-knight-continental-armour-in-england-1435-1500-by-tobias-capwell/

Book 1, Armour of the English Knight 1400-1450 is currently out of print, but is coming out in softcover in the Autumn, and readers can express interest in that here:

https://www.olympiaauctions.com/about-us/publications/armour-of-the-english-knight-1400-1450-by-tobias-capwell/

Also releasing in the autumn is Armour of the English Knight: An Armourers’ Album ; the pre-order for that should be open soon.

‘Richard III: The New Evidence’ on YouTube:

The first online talk by Dr Toby Capwell, ‘The Scoliotic Knight: Encounters with Richard III’ is here:

https://swordschool.teachable.com/l/pdp/the-scoliotic-knight-encounters-with-richard-iii

Leave a comment