I have become rather interested in the terrible demise of Sir William Cantilupe (born circa 1345 – died March 1375), the truth about which fascinates people to this day. There are various papers and articles about it online, and I had already commenced a article for this blog when I learned of a full-length book by Dr Melissa Julian-Jones called Murder During the Hundred Years War: The Curious Case of Sir William Cantilupe, which I have purchased and read. I won’t be giving the denouement away, but I do intend to set the background to the murders. The identity of the murderer/s and their motives I leave for the reader to decide. But if you are someone to whom spoilers are essential, you’ll find useful links near the end of this post.

But first, I have one small quibble about the book. The back cover blurb begins as follows: “…Since his murder in 1375, the death of Sir William Cantilupe has remained one of the most intriguing medieval mysteries of all time…” My quibble is that while murder was definitely intriguing, is it really one of the most intriguing of all time?

After all, it cannot be said to compete with the disappearance of Richard III’s nephews, the Princes in the Tower, whose fate the Tudors (and thus posterity) have been determined to say was foul murder at Uncle Richard’s hands. But then again, that particular mystery has surely been solved by Philippa Langley and the Missing Princes Project. The boys were not murdered at all! Another aspect of the boys’ vanishment will—hopefully—hopefully to soon be revealed at Coldridge church, again with Philippa Langley’s inspirational involvement.

Beside the Richard III’s nephews and Coldridge, the savage fate of Sir William Cantilupe is rather underwhelming, although certainly not to the point of obscurity. I was certainly drawn enough to delve a little further. Yet I hadn’t even heard of it until a few weeks ago, and even then it was happened upon by accident while looking for something else. But that aside, the book by Dr Melissa Julian-Jones dissects the facts with the meticulousness of an experienced surgeon with the sharpest of scalpels.

I’m not really sure what to think of the victim, William Cantilupe, who was only thirty when he was despatched. I certainly feel sorry for anyone who dies in such a calculatedly coldheartedly and bloody way, but had he garnered liking and support during his lifetime? It seems maybe not because his wife, her maid, and the entire household of servants, as well as influential landowner Sir Henry Paynel§ and the county sheriff, came under suspicion of killing him. So suspects in his murder were certainly not lacking!

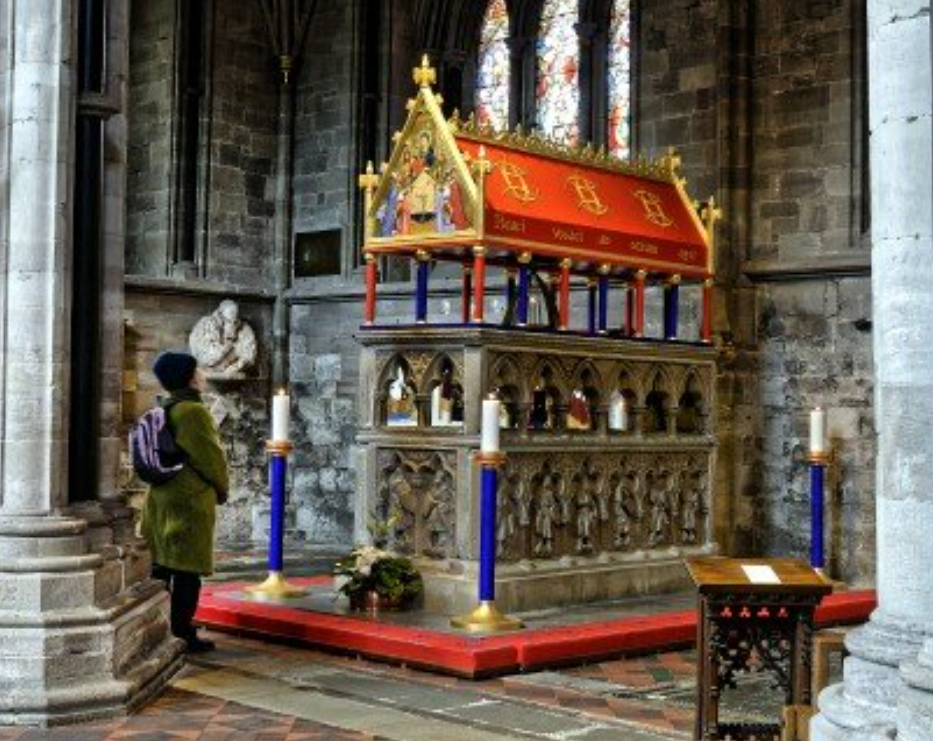

The Barons Cantilupe were an important family of magnates with many manors and holdings across Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire. They came over to England with the Conqueror and did very well under him. They even produced a saint (St Thomas de Cantilupe, Bishop of Hereford, see here https://www.saintforaminute.com/saints/saint_thomas_of_hereford).

But then the family’s prominence dwindled, and finally a blip happened in the succession. I don’t really understand it, but William’s father was overlooked in favour of his two sons. Then, as they both predeceased him, he became the 4th Baron Cantilupe anyway. See https://murreyandblue.org/2024/10/02/another-nobleman-shoving-his-firstborn-son-aside/. The barony then died with him. Sir William Cantilupe was the younger, and neither he nor his elder brother Nicholas produced children. Their line of the Cantilupes ended finally when William and his wife, Maud Nevill, spent Lent and Holy Week 1375 at her Lincolnshire manor of Scotton*, see here, just over five miles south of Scunthorpe. William’s chief manor was at Greasley Castle in neighbouring Nottinghamshire. (See https://murreyandblue.org/2024/05/13/the-mystery-castle-i-didnt-know-i-was-passing-in-1957-1960/ and https://murreyandblue.org/2023/03/11/what-do-you-know-of-greasley-castle/, both written before I knew the details of Sir William’s murder.)

Like Scotton Manor, Greasley Castle (see here) has now almost disappeared, but enough of it remains for recent excavations to have revealed it to have resembled Haddon Hall. So Greasley was quite an impressive and sumptuous residence built by William’s elder brother, Nicholas.

At Scotton William had simply disappeared. He’d retired for the night, locked his door and said his prayers, and that was the last that was known. After his vanishment, his wife promptly closed the manor house and then she and the servants left. No one knew where she’d gone. Certainly not to Greasley or any of William’s manors.

Then, some months after he’d last been seen, William’s body was discovered in a state of decomposition in a ditch near the village of Grayingham, see here, about five and a half miles southeast of Scotton in the West Lyndsey district of Lincolnshire. Decomposition or not, examination soon revealed that attempts had been made to conceal numerous knife wounds. The Coroner of Lincolnshire, William de Kirkton, a London merchant, was sent for immediately. On examining the body on site he knew straightaway that either Sir William had been set upon by scoundrels while out riding and his body dumped in the ditch, or he’d been murdered elsewhere and his body brought here. Either way, he’d been killed and to disguise the wounds he’d been dressed in clean clothes afterward!

There were a number of bands of criminals in the area, and it might have been any one of them, but surely they would simply have killed and dumped him, to heck with any messing with clean clothes. Or….had he been done away with much closer to home? Maybe even at home, at the now deserted manor of Scotton? His wounds had certainly been thoroughly cleansed with what had to be boiling water, to seal them in readiness for clean clothes.

So, what had happened to Sir William? Where was Maud, Lady Cantilupe? Why had she closed Scotton Manor and scuttled away? Not a single servant remained. It certainly pointed to something dire having gone on there, which prompted the increasing suspicion that Maud had something to do with William’s disappearance. If so, the case could become an early case under the Petty Treason Act of 1351 (see here Treason – Legal history: England & common law tradition – Oxford LibGuides at Oxford University), which dealt with the slaying of a man by his wife or servant. Perhaps Coroner de Kirkton could see himself with the kudos of discovering one of England’s first cases of petty treason.

Following de Kirkton’s initial examination there was an investigation by Sir Thomas de Kydale, Sheriff of Lincolnshire, a widower who was widely suspected of being Maud’s lover whenever Sir William was away on military service. Which was often. The outcome of the findings of both coroner and sheriff was a major trial in the Court of the King’s Bench in Lincoln (see here for what happened to the medieval building here and for the court itself here) at which no fewer than fifteen people were indicted for the crime! Eventually, after very lengthy proceedings, two relatively insignificant men were convicted and hanged for the murder of Sir William Cantilupe.

Maybe the two men were guilty, but had they acted alone? It doesn’t seem likely to me when among the fifteen on trial were Maud and the prominent Sir Ralph Paynel *, and when the sheriff, Maud’s supposed lover, was in charge of the trial. The latter would be very impartial, of course. Hmm….

At the least Sheriff de Kydale was guilty of a conflict of interests. It wouldn’t be permitted today, that’s for sure. At least, I hope not. But let’s face it, the likes of Lady Cantilupe, Sir Ralph Paynel (see here) and the Sheriff of Lincolnshire didn’t take orders from men as lowly as the two who’d eventually be convicted and hanged for the murder. Besides which, Maud’s whereabouts had still to be determined. Then, at last, she was located at Caythorpe, see here, one of Sir Ralph’s manors just over thirty miles from Scotton.

What, exactly, was Sir Ralph’s part in it all? Why would he be involved in what was now clearly a terrible murder? His Cantilupe connection until then had been that his daughter, Katherine, had been married to Sir William’s late elder brother, Nicholas, but that was all. Katherine had since remarried.

Both the Cantilupes and the Paynels originated in France and ended up with English branches. Some years after the Cantilupe murder, another Paynel, the French governess of Richard II’s second queen, the child Isabella of France, was at the centre of another scandal. (See my double articles The de Courcy Matter Part I: According to English records…. – murreyandblue and https://murreyandblue.org/2024/04/24/the-de-courcy-matter-part-ii-the-french-side-of-the-story/)

The heart of the Cantilupe murder mystery reaches back to William’s elder brother Nicholas Cantilupe, from whom Katherine Paynel had striven to escape. I will say no more of the rather salacious details of that particular union, or indeed about the murder of William Cantilupe. To do that would indeed give away spoilers. But you now have most of the dramatis personae.

But the book isn’t perfect. To begin with it doesn’t have an index. I always find this very annoying, but then so is a very cursory index. The best ones are thorough with plenty of detail. But that’s just my pov, and you are welcome to ignore it.

What is more serious about the book is that several times in the text Julian-Jones observes that nothing more is heard of Sir William Cantilupe from the time of his return to England (after his brother’s death in 1371) until his own death in the spring of 1375. This is not so, because Sir William accompanied John of Gaunt on the Great Chevauchée of 1373. A chevauchée is “….a military raid by cavalry through enemy territory, designed to disrupt rural communities and weaken an opponent….” This is rather a mild way of putting it, for these operations were very bloody and vicious. This one would move from Calais down through France to the English territory of Bordeaux, Aquitaine.

After a last-minute change of plan that moved the departure from Plymouth to Dover and Sandwich instead, Gaunt eventually set sail for Calais on 11 July 1373 (Helen Carr, The Red Prince, 100). In Simon Walker’s excellent book The Lancastrian Affinity 1361-1399, on page 55, I found the following:

“….It is only possible to catch an occasional glimpse of what this rapid mobilization [preparing to leave on the chevauchée] could mean for a retainer; to see Sir William Cantilupe unable to complete the enfeoffment of his lands because he had to follow the duke of Lancaster to France in the morning….”

The years for which Sir William took out letters of protection before going overseas in the duke’s company are 1370, 1372 and 1373. So he was definitely active after 1371 and before his death in 1375.

The chevauchée was a dismal, very expensive failure that cost the lives of many English soldiers, and the now very unpopular duke returned to England from Bordeaux and arrived in Dartmouth on 26 April 1374. If Sir William returned with him, then there was just about another year to go before he breathed his last. Was that final year the straw that broke the camel’s back of his marriage? Did his renewed presence upset the happy balance the household had enjoyed in his absence? We’ll never know, but murdered he was, with considerable premeditation. We have the list of possible culprits, but who did what? And why had they murdered William?

But I will leave the Cantilupe murder mystery here, in the hope that I’ve tickled your fancy sufficiently to read Dr Melissa Julian-Jones’s book Murder During the Hundred Years War: The Curious Case of Sir William Cantilupe which, chevauchée notwithstanding, is a Very Good Read.

However, if you’re a person who might read the last page of an Agatha Christie thriller first, there are a number of sites online that come with spoilers about William’s murder. Go here (PDF) Murder, Mayhem and a very small Penis | Frederik Pedersen – Academia.edu, which can be downloaded free and also found at https://www.medievalists.net/2013/07/murder-mayhem-and-a-very-small-penis/. More is to be read here Murder of William de Cantilupe – Wikipedia, and here The 1375 Murder of William Cantilupe in Medieval England w/ Melissa Julian-Jones (youtube.com).

*The manor house at Scotton is no more, but there is a 19th-century Manor House Farm which may possibly be built on the original site. See here.

§For a 15th century Paynel scandal, see https://murreyandblue.org/2024/08/31/a-shocking-family-scandal-from-15th-century-lincolnshire/

Leave a comment