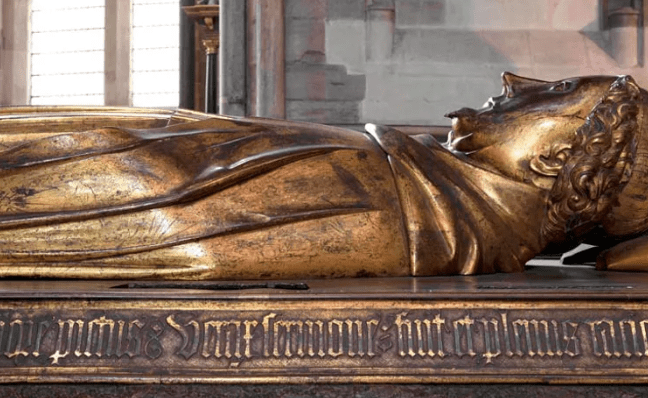

The above image clearly shows part of the inscription around the tomb. From Westminster Abbey Library

The tomb of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia in Westminster Abbey is very well known and recognised. The effigies once held hands but the hands are now missing, and the original magnificence of the tomb can only be imagined. If you go to this link and scroll down to the section headed Burial and Monument you can read a lengthy description and history of the monument.

What isn’t in the article is that although the tomb (at first containing only the remains of Anne of Bohemia, who predeceased her husband by some five years) was originally erected in Westminster Abbey, it didn’t suit Henry IV, Richard’s lethal, usurping cousin, to leave it there. Henry didn’t want too much attention drawn to the predecessor he’d ousted illegally and killed, because Richard hadn’t been the hated monarch Henry wanted him to have been. Maybe you’ve heard something along these lines before? Yes. Richard III and his Anne, and another despicable, usurping Henry.

When the imprisoned Richard II was assassinated at Pontefract Castle, at around St Valentine’s Day 1400, his body was brought south and a funeral service and interment held in Westminster Abbey.

The entire tomb was then removed to the more rural surroundings of King’s Langley in Hertfordshire, where it wouldn’t attract too much devotion and maybe become the centre of a cult. Richard had to be shoved into the shadows and forgotten.

There Richard and Anne remained throughout Henry’s reign, until Henry V, the usurper’s son, ascended the throne. At this point Richard and Anne and their gilded memorial were suddenly returned in splendour to Westminster Abbey. Why? Why?

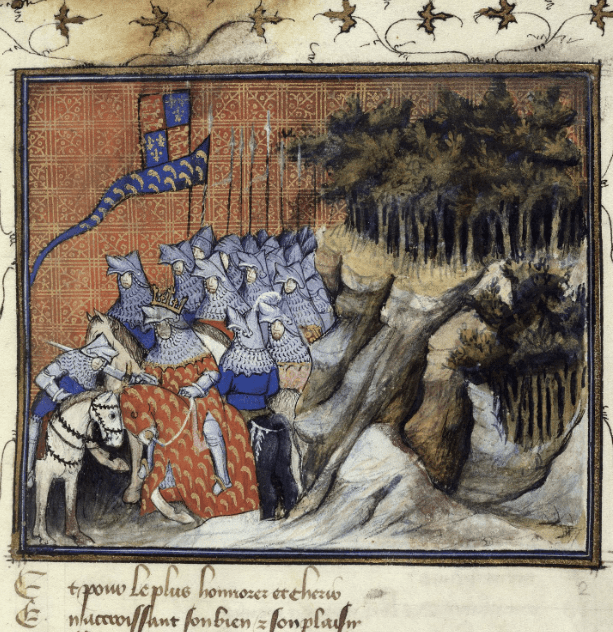

Well, for the answer it’s necessary to go back to Richard’s reign, during which he made two expeditions to quell unrest in Ireland. On the second of these he knighted Henry of Monmouth, the future Henry V, then only twelve, with whom Richard had a very good relationship. Henry of Monmouth was Shakespeare’s Prince Hal….a name that was also given to the magnificent showjumping horse of Pat Smythe (for those who remember!)

A little before leaving on this second expedition, the gilded effigies on the Westminster Abbey tomb were finally ready and put in their place. Royal tombs required a lot of preparation, and so were usually commenced well before death, as happened with the pharaohs. John of Gaunt had certainly had his begun a long time before he was eventually laid to rest in it, alongside his adored first duchess, Blanche of Lancaser.

Such foresight wasn’t always possible, of course. Tutankhamun’s tomb hadn’t been made for him. It’s believed that his sudden death at such a young age meant he had to be lain hastily somewhere belonging to someone else. But in England in 1399, it so happens that Richard’s tomb with Anne was mostly ready.

Henry of Monmouth’s relationship with his own father was not good. That father was Henry of Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, soon to be King Henry IV. Richard II and Lancaster had never been loving cousins, and after the death in February 1399 of Henry’s illustrious father, John of Gaunt, things got to the point where Richard exiled Henry and temporarily confiscated his estates, inheritance and so on. Temporarily, please note, because it’s usually claimed that Richard snatched the lot for good and all. In fact it is recorded that it was “….until Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford [which, technically, he still was at this point], or his heir, shall have sued the same out of the king’s hands according to the law of the land….” There was no need for this to have been included if Richard had no intention of ever returning the inheritance.

Perhaps Richard had just had it up to the gills with his cousin for the time being and saw the banishment as an opportunity for both parties to cool off. Plus, of course, surly Lancaster was an over-mighty subject who had rather too much power and money for royal comfort. But nowhere is it recorded that the banishment or confiscation was to be permanent.

Or perhaps, it is suggested, Richard was actually intending to return it all to Henry’s son and heir, whom he, Richard, may well have come to regard as his own heir. He hadn’t permitted Henry of Monmouth to accompany his father into exile, but kept the boy in his own household. Far from resenting this, young Henry seems to have regarded Richard with devotion!

When Richard and Henry of Monmouth were in Ireland, Lancaster came back with an invading army, saying it was only to regain his inheritance, but actually he had an eye on taking the throne as well. Richard rushed back, but he’d been out-manoeuvred and the end of his reign—and his life—were now very close.

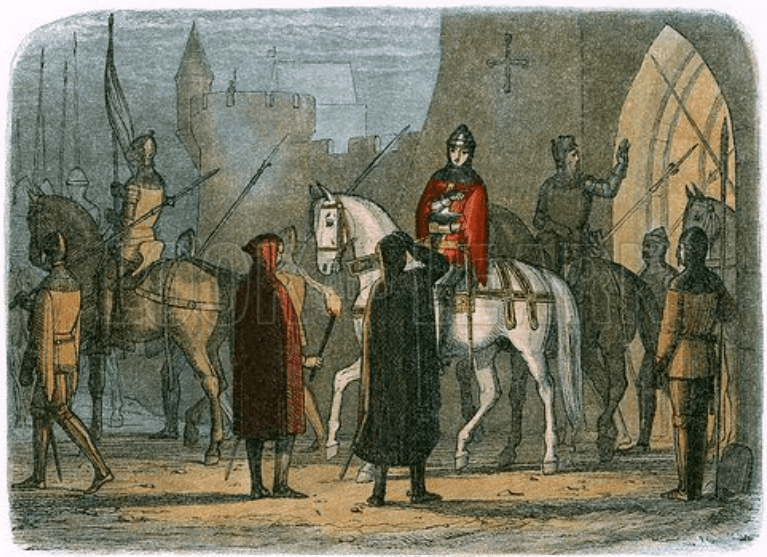

Richard, young Henry and Lancaster—no, let’s call the latter Henry IV because his coronation was imminent—met at Chester today, 16 August, in 1399. The boy had to be more or less wrenched from Richard’s side to go with his father.

Henry of Monmouth—the new Prince of Wales—had a high regard and affection for Richard II that endured, and when he ascended the throne himself one of his first acts was to order Richard and Anne’s tomb to be brought from King’s Langley to its proper place in Westminster Abbey. Please note that at this point it bore no inscription. Richard had never written or suggested one, but then he hadn’t known he was to die before his time.

It seems that Henry V had a heavy conscience about his father’s actions in 1399 and wanted—needed—to make reparation. At the same time he felt he had to justify his own occupation of the throne, and being a zealously pious man, he seems to have found it necessary to make Richard appear to share his religious fanaticism. I say fanaticism because Henry, the hero of Agincourt, supported some of the more unpleasant extremes of the Church at that time. Especially when it came to the Lollards and other heretics. This meant that people who didn’t hold rigidly to the tenets of the Church were to be burned if they didn’t recant. The first such burning in England had been in the reign of Henry IV, not Richard II.

Richard, on the other hand, had been more or less conventional, and lenient with heretics. Indeed, there were Lollards among his closest friends and advisers. They were openly heretical, and followed the dissident priest John Wycliffe, who was a deep thorn in the side of the Church throughout his life. He translated the Bible into English and preached that the ordinary people should be allowed to read it.

This was something that appalled the Church, which wanted complete control of everything, hence the constant use of Latin. Wycliffe preached that the Church was greedy and in sin, and should (among other things) give up its immense treasure of worldly possessions. There was more to Lollardry than that, of course, but you get the drift of why the Church loathed them so much and hounded them as savagely as it could.

But although Richard II was constantly badgered to be rid of his Lollard friends and to do something about the rise of Lollardry, he didn’t. He wasn’t a Lollard himself but was at ease about tolerating them. Oh, he submitted to Church bullying now and then, such as saying he’d do what was wanted, but then he’d dilly-dally and drag it all on without doing anything. How could he do as the Church pressured when his close friends, his mother Joan of Kent, his uncle John of Gaunt, and even his beloved Queen Anne were open to Lollard views? Anne had graciously accepted a translation of the Bible into English (a huge no-no for the horrified Church) and in the case of John of Gaunt that openness led to publicly and forcibly supporting Wycliffe with arms when the latter had to appear before Archbishop of Canterbury William Courtenay at St Paul’s Cathedral.

So Richard himself was tolerant, that’s clear enough, and his responses didn’t go even close to satisfying the Church, which went ape, as the quaint saying goes. Courtenay accused Richard vociferously and publicly, listing all manner of “misdeeds”. In the end it almost came to bloodshed during a chance encounter on the Thames, when Courtenay had another verbal go at the king. Richard was so furious he drew his sword and would have leapt from his barge to Courtenay’s had not his companions held him back. But for their restraint, he might have taken out William Courtenay. Some might say it was a pity he didn’t.

Richard must have felt the same about Courtenay’s obnoxious successor, Thomas Arundel, who was quite a piece of work. In my opinion. It’s hard to imagine the reaction of Courtenay and Arundel to today’s obsession with freedom of speech, religion and thought. If they had their way I certainly wouldn’t be making free with words like these!

Which brings me to the odd matter of the inscription of Richard’s Westminster tomb, which you can see in the first image of this article. In the link https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/royals/richard-ii-and-anne-of-bohemia a translation from the Latin is given as:

“Sage and elegant, lawfully Richard II, conquered by fate he lies here depicted beneath this marble. He was truthful in discourse and full of reason: Tall in body, he was prudent in his mind as Homer. He showed favour to the Church, he overthrew the proud and threw down anybody who violated the royal prerogative. He crushed heretics and laid low their friends. O merciful Christ, to whom he was devoted, may you save [Richard], through the prayers of the Baptist, whom he esteemed.“

I’ve drawn attention to the sentence about crushing heretics and laying low their friends. Richard II clearly did no such thing. But in spite of his closeness to Richard, Henry V did hold such views.

Henry knew that Richard had been the true and rightful king, coerced into surrendering the crown and brutally displaced by Henry IV. Now Henry V’s ethos was to leapfrog his own father as if he, Henry V, were Richard’s immediate true and rightful heir. His son, almost. There had never been a Henry IV! Perhaps Richard had indeed intended Henry of Monmouth to succeed him. We’ll never know. But I think we can be sure that Richard wouldn’t have set about burning Lollards!

So the general thought now is that Henry V composed, or caused to be composed, the inscription on Richard II’s memorial in Westminster Abbey. It had nothing to do with the wishes of Richard himself, and eveything to do with Henry V’s desire to align Richard with his own extreme views on Lollardy.

I have written this after reading about the tomb in Terry Jones’s Who Murdered Chaucer? Terry was a strong supporter of Richard II, once as rare a bird as supporters of Richard III. But things are changing rapidly for the latter king, and rightly so. Now let’s hope that Richard II can be redeemed as well, because he was not the unhinged despot foisted on us by his Lancastrian usurper and numerous glib traditional historians.

Nor did he revel in setting fire to heretics!

Leave a comment