Today we all worry about global catastrophe, with terrible weather phenomena and all manner of fearful occurrences. Well, we understand more now, but what if we’d lived in medieval England? Back then everyone believed quite genuinely and fearfully in the supernatural, magic, Otherworldly beings, the wrath of God and the evil of the Devil.

It was while I was researching the weather and astral phenomena of the late 14th century that I came upon several years that appear to have had a goodly share of awesome events. I have chosen the trials of 1385.

At first it seemed not too bad. January and February were unusually wet here, but in Europe there was a great freeze.

There was alarm in England as a French invasion was threatened, and then in February they did invade along the south coast, ransacking some towns before departing again. It caused great unease, and fear that a far greater invasion might ensue.

From this same February until July, things became excessively warm and dry. At the end of May the French fleet, originally intended for an invasion of Engand, was diverted elsewhere and managed to give an English blockade the slip. In the meantime they’d sent a smaller fleet and a force to their ally Scotland. There they combined to harry the northern counties of England. The English king, 17-year-old Richard II, planned a campaign to take them on, and began to assemble a huge force to go north. According to Saul this force was the largest of the 14th century, consisting of 14,000 men and virtually all the magnates and bannerets of the land.

In the meantime, from May onward a proper drought set in that made it possible to ford many rivers which hitherto had required a bridge or a ferry. Wells dried up, bournes ceased, streams shrank to a trickle, and crops and beasts struggled. Pasture became more and more sparse for the latter. The sun blazed down relentlessly from a flawless blue sky and there was none of the gentle rain that was the usual mark of the English summer. This awful drought wouldn’t end until 5 September 1385 when there would be a monstrous thunderstorm.

I do not pretend to be an astronomer, or indeed a qualified historian, but I hope I have gathered the following events in the correct order. It isn’t always easy to sort through the different references, some of which downright contradict one another!

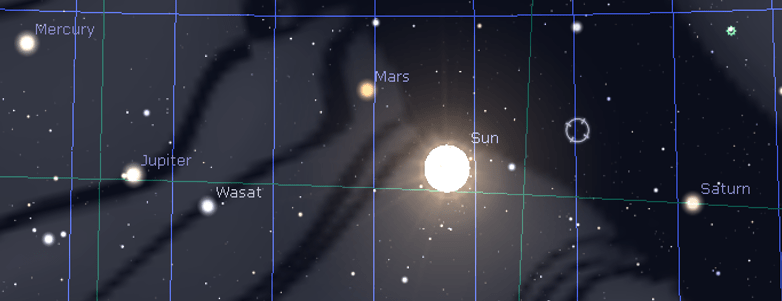

Just before midnight on 13/14 May 1385 there was a rare conjunction of the planets—Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and the Sun. It was at an angle of 3.8o and because it was night was visible with the naked eye, which is why Chaucer was able to see it. In his words he saw, conjoined on the very edge of Cancer, “the bente moon with hire hornes pale, Saturn and Jove”. He wove what he saw into Troilus and Criseyde, and you can read many more details here A Planetary Date for Chaucer’s Troilus on JSTOR. It seems that this precise arrangement in the sky can be pinpointed to this month and year. And his choice is hardly likely to be a coincidence.

One thing’s certain, for astronomers and astrologers who knew all about the heavens, it seemed likely to be a portent of something momentous…and probably not in a pleasant way! Perchance the annihilation of the English military host!

In spite of the Chaucerian evidence, the exact dating of the above conjunction is disputed, with some sources saying it was 3 May (and they add an accompanying earthquake for good measure) while others insist it was 13/14 May. And while the people as a whole might not actually notice anything untoward, word would soon spread, as would a degree of panic.

During the long march north, the English host had camped in the meadows south of York when, at 3 p.m. on 14 July, a terrifying thunderstorm swept England, and the following day, 15 July, there was an alarming phenomenon in the sky. You can read about it in this extract from the JSTOR link above: “….at London and likewise at Dover, there appeared after sunset a kind of fire in the shape of a head in the south part of the heavens, stretching out to the northern quarter, which flew away, dividing itself into three parts, and travelled in the air like a bird of the woods in flight. At length they joined as one and suddenly disappeared….” (Source: C.E. Britton, A Meteorological Chronology to A.D. 1450 (London: H.M.S.O., 1937), 149; also noted by John Malvern, a monk of Worcester, who certainly contributed to the Polychronicon, begun by Ranulph Higden, a monk of Chester, but continued the chronicle only as far as 1377.)

Then, at nine in the evening on 18 July 1385 there really was an earthquake!

If this earthquake was experienced in York, I can imagine the superstitious fear and unrest throughout the army. First the seemingly endless drought, and now this! It was blamed too on the preceding storm and the dreadful lights in the sky. Might the earthquake be another sign of great disapproval from on high? But the campaign was to continue, and the English would reach Edinburgh. The Scots and French retreated before the, refusing the give battle, and the campaign rather fizzled out. But the French fell out with their Scottish hosts, who wanted them to pay for everything. Nor did the Scots approve of the French commander’s amorous liaison with a highborn Scottish lady. And so the French returned to their homeland.

On 21 June 1385 there was another conjunction, although this time nothing was visible to the naked eye because it happened in daylight and the sun’s dazzle banished the lights of the planets.

I am grateful to Dr Diana Hannikainen of Sky & Telescope magazine, Cambridge, MA, for her kind help with my amateur enquiries. In her words concerning this 1385 conjunction: “….the planets (Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, Saturn) are indeed all bunched up near the Sun – the angular separation between Mercury and Saturn is a little more than 9 degrees, while between Jupiter and Saturn it’s about 6.5 degrees….However, it being a daytime conjunction, none of the planets would have been visible – the Sun’s light would have completely washed them out….”

She also sent me a link to a free downloadable planetarium software https://stellarium.org/ that allows you to input any date and any geographic location. I’m afraid I haven’t mastered it, but that’s my gormlessness not the fault of the software!😊

On 20 August 1385, while at Newcastle-upon-Tyne during their return south, the royal army was almost washed away by a tremendous deluge. It must have been one heck of a downpour because it was worthy of recording in the chronicles!

I said at the beginning that the excessive heat ended on 5 September, and so it did, with a cataclysmic thunderstorm that brought much needed rain. And undoubtedly it brought flash floods as well, although I don’t know for certain. The storm was clearly a momentous event, but at least it ended the awful heat and drought. However, if the long-suffering folk of England thought their trials were over, they were wrong.

When the Feast of Holy Cross arrived—14 September 1385—so did a second earthquake. Walsingham said it was ‘Ante medium noctis Inventionis Sanctae Crucis’, i.e. before midnight on the feast of Discovery of the Holy Cross. According to The Rise of Alchemy in 14th Century England by Hughes—The conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter caused the earthquake, which was a manifestation of the hidden powers in the earth and meant that a truly bloody conflict between England and France was imminent. Hmm….

Finally, at Michaelmas, 29 September 1385, according to Whittock’s Life in the Middle Ages, the sky burned red all night!

So, all in all, it’s a wonder anyone in England survived to reach 1386.

Leave a comment