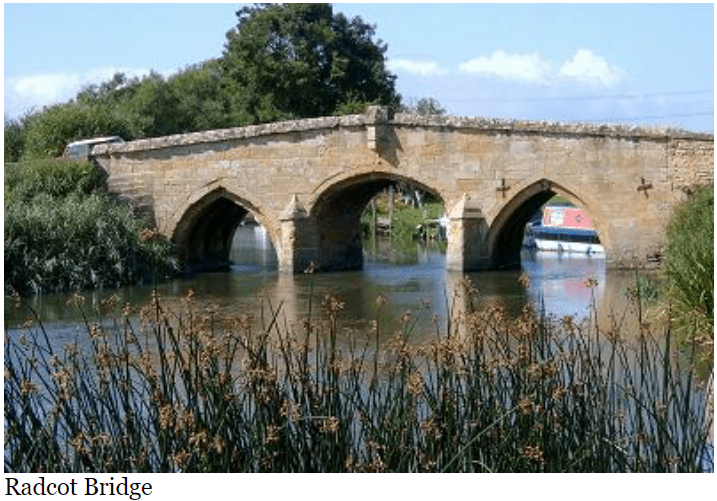

My meanderings in the name of research sometimes turn up things that rather bemuse me. This time I was in hot pursuit of Sir Thomas Molyneux of Cuerdale, who was murdered rather nastily by Thomas Mortimer Thomas Mortimer at the Battle of Radcot Bridge on 19 December 1387. Molyneux had once been John of Gaunt’s man, but by then had fallen out with him and was instead the man of Richard II’s favourite, Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland.

You can read about the battle here, and in Holinshed’s Chronicles where the battle is described and (while incorrectly identifying Mortimer as Roger) Molyneux’s death is described:-

“In 1387, King Richard II sent secretly to Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland, who was levying troops in Wales, to come to him with all speed, to aid him with the Duke of Gloucester and his friends; and commissioned at the same time Sir Thomas Molineux de Cuerdale, Constable of Chester, a man of great influence in Cheshire and Lancashire, and the Sheriff of Chester, to raise troops, and to accompany and safe conduct the Duke of Ireland to the Kings presence. Molineux executed his commission with great zeal, imprisoning all who would not join him. Thus was raised an army of 5,000 men. The Duke of Ireland, having with him Molineux, Vernon, and Ratcliffe, rode forward ‘in statelie and glorious arraie.’ Supposing that none durst come forth to withstand him. Nevertheless, when he came to Radcot Bridge, four miles from Chipping Norton, he suddenly espied the army of the lords; and finding that some of his troops refused to fight, he began to wax faint hearted, and to prepare to escape by flight, in which he succeeded ; but Thomas Molineux determined to fight it out. Nevertheless, when he had fought a little , and perceived it would not avail him to tarry longer, he likewise, as one despairing of the victory, betook himself to flight ; and plunging into the river, it chanced that Sir Roger Mortimer, being present, amongst others, called him to come out of the water to him, threatening to shoot him through with arrows, in the river, if he did not. ‘If I come,’ said Molineux, “will ye save my life?’ ‘I will make ye no such promise,’ replied Sir Roger Mortimer, ‘but, notwithstanding, either come up, or thou shalt presently die for it.’ ‘Well then,’ said Molineux, ‘if there be no other remedy, suffer me to come up, and let me try with hand blows, either with you or some other, and so die like a man.’ But as he came up, the knight caught him by the helmet, plucked it off his head, and straightways drawing his dagger, stroke him into the brains, and so dispatched him. Molineux, a varlet, and a boy were the only slain in the engagement; 800 men fled into the marsh, and were drowned ; the rest were surrounded, stript, and sent home. The Duke of Ireland made his escape to the Continent ; and the King returned to London.”

So I visited British History Online, and found that the original manor house at Cuerdale was destroyed by fire in the spring of 1355. Unfortunately I cannot find a single illustration of previous versions of Cuerdale Hall, only what is there now. Anyway, the burned-down house was replaced by a property which was presumably the one Thomas Molyneux held, and which by 1666 had been greatly extended and improved. The following extract about this latter version of Cuerdale Hall is from British History Online :-

“….the manor [Cuerdale in Lancashire] passed with the other estates of the Osbaldeston family, until alienated on 1 March 1614 by Edward Osbaldeston to Ralph Assheton of Lever….[whose]….house had twelve hearths liable to the tax in 1666, but no other had as many as three; the total number of hearths in the township was twenty-five.”

The above concerns the house as it was in 1666, so I doubt very much if Sir Thomas Molyneux had anywhere near that many hearths. He wasn’t high nobility, but Lancashire gentry, although he rose high in the service of John of Gaunt, so maybe one hearth in the middle of the great hall would have been his lot? Yet by the time of the Great Fire of London there were twelve taxable hearths. Twelve? Can you imagine running that many in the England of 2024? You’d have to cough up a fortune to provide fuel for them, let alone pay steep tax on top for the privilege. Well, we pay taxes on just about everything today so no difference there, except for the sums involved.

I imagine in 2024 the place would be darned cold in winter, with only a couple of those heaths flickering with logs and cheery flames. Or the central heating turned down to a minimum. Maybe a hearth or two for effect in the main living rooms. The rest of the place would be Icicleland. As maybe it was back then too. These things are all relative.

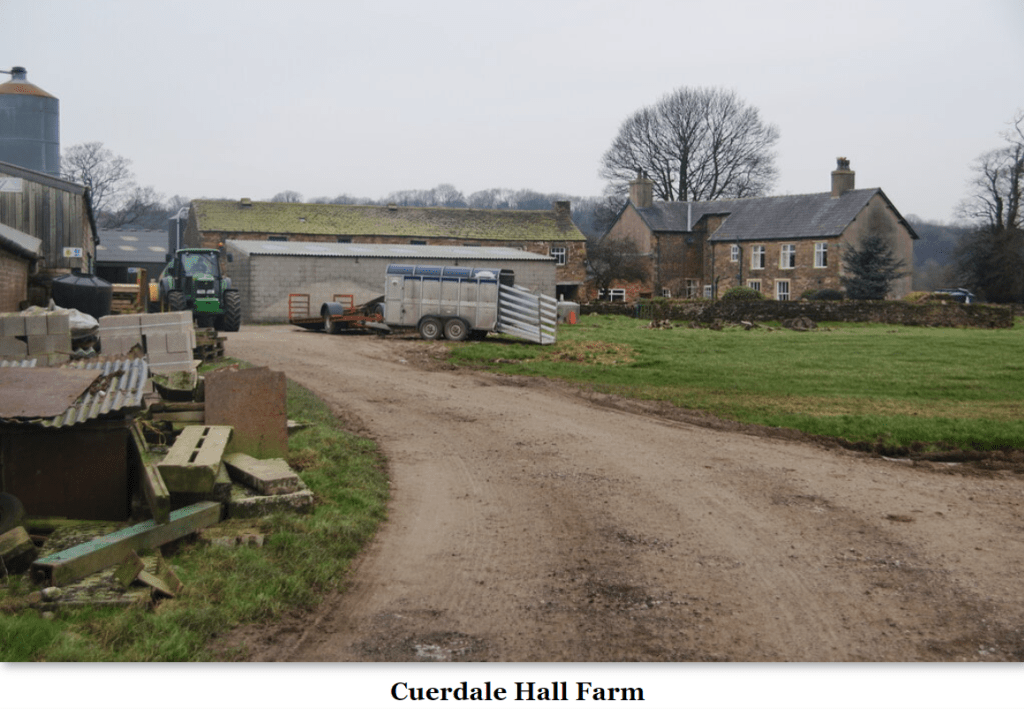

However, the house Sir Thomas Molyneux may have known in the 14th century has disappeared. One has to say the mighty have fallen, for there certainly aren’t twelve hearths there now. Indeed, there’s no sign at all of the medieval building (well, almost no sign), or indeed of the seventeenth-century replacement! Now Cuerdale Hall is merely a rather nondescript two-storey farmhouse which is famous for the discovery in 1840 of the Cuerdale Hoard CuerdaleHoard. You can read about the present house here here:-

“The house is now a two-storey farmhouse of brick and stone, with slate roofs. The present building is said to date from a rebuilding in 1700 for a junior branch of the Assheton family, but it may incorporate some elements of the earlier hall house (which was taxed on 12 hearths in 1666) and was much altered and extended later. The house is now roughly T-shaped, and the earliest work is in the west wing. Inside, the house preserves two fine dog-leg staircases and one small panelled room upstairs. An 18th century sundial, formerly at Cuerdale, is now at Downham. The house has long been let as a farmhouse and divided into two dwellings, and is now surrounded by modern farm buildings, but still belongs to the Asshetons.”

And in the BHO entry (Townships: Cuerdale | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk):-

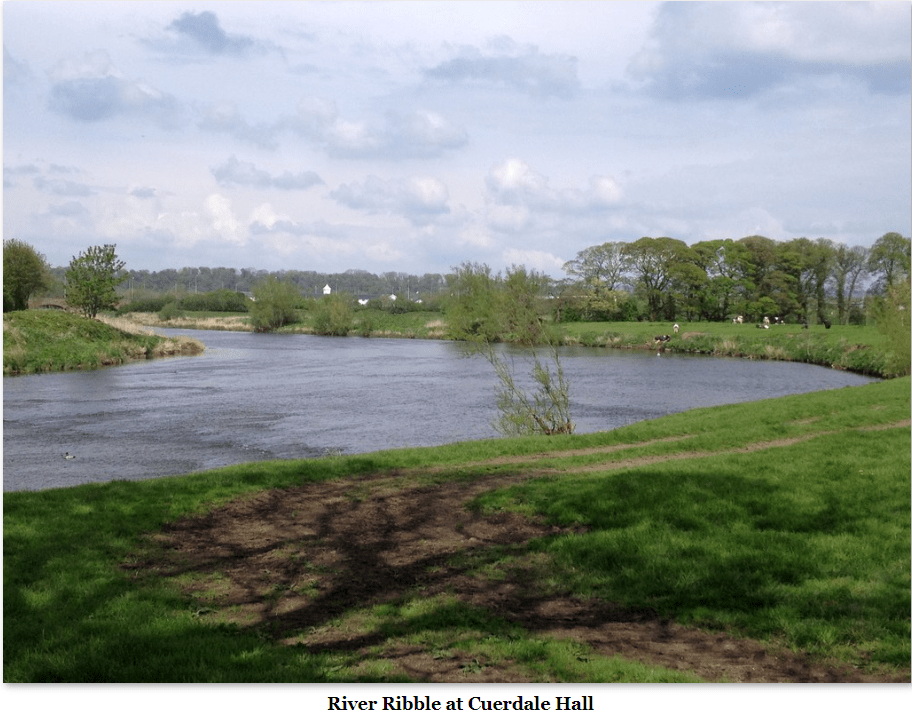

“CUERDALE HALL stands in a low situation near the south bank of the Ribble about a mile north-east of Walton-le-Dale, the principal front facing north to the river. The house, which is of two stories, is now divided into two and is of little architectural interest, so many alterations and additions having been made that the disposition of the original plan has been lost and the external appearance of the building completely changed. It appears to have been a 17th-century structure of brick and stone, some portions of which remain at the back, where two stone buttresses against the old brick wall probably mark the position of the hall.”

You can read more here CUERDALE HALL, Cuerdale – 1073028 | Historic England

Leave a comment