You all know the old saying “Curiosity killed the cat”. I’m one such cat and often see something funny or odd in the blandest of sentences. I just can’t help it. Well, this irrepressible curiosity has been pricked again.

At the age of 10, in the summer of 1340, Edward of Woodstock, the young Prince of Wales (to one day be the renowned Black Prince) visited the castle at Berkeley in Gloucestershire. I’m surprised that he should go there at all, given that the Lord Berkeley of the time was the same man who’d been there in that very same castle in 1327, before the prince was born, when a terrible fate apparently fell the boy’s grandfather, Edward II. But that’s a matter for another article.

I learned of this 1340 visit when reading Edward Prince of Wales and Aquitaine by Richard Barber, page 37, where the author notes that on leaving Berkeley the prince “had to” hire a boy to guide the royal party. Barber adds that this is “a vivid reminder of the difficulties of medieval travel when there were no made-up roads”.

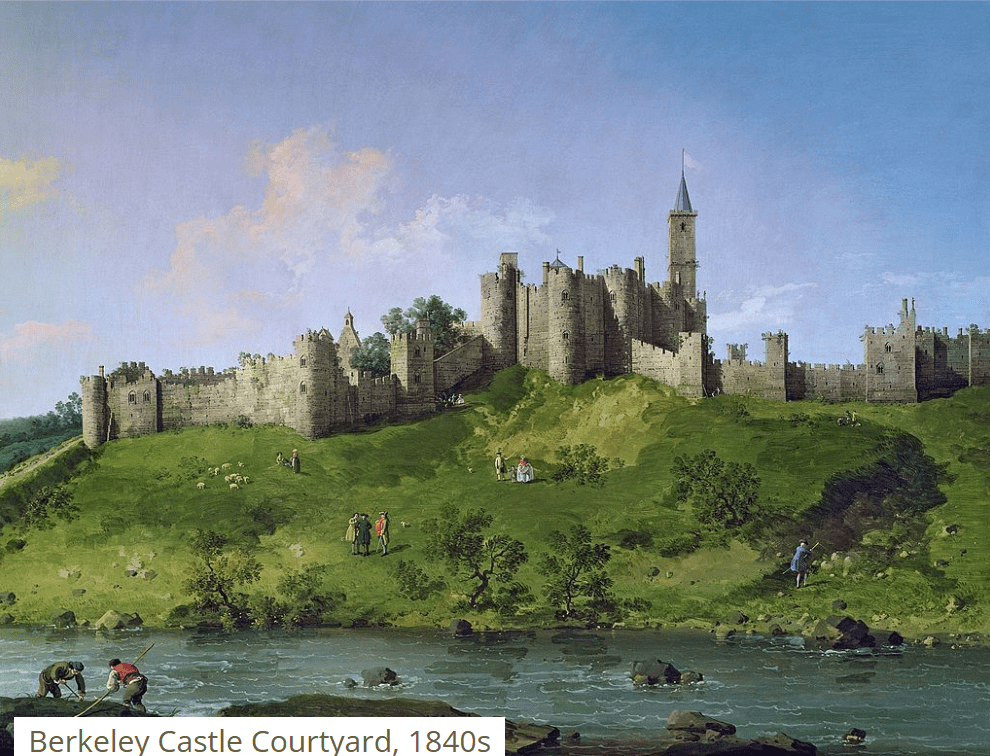

Indeed it is such a reminder, although I confess to being a little confounded by the suggestion that Berkeley lacked roads entirely. It was a strategically important site, of course, because both castle and town were on a small hill overlooking the nearby Severn estuary, and the comings and goings of vessels could be easily seen, as could unwelcome foreign visitors! You can see this clearly in the painting below, which shows Berkeley’s low hill and position regarding the Severn estuary, which itself can be seen from the right to left above the church. Berkeley Pill, which I mention in the next paragraph, is hidden behind the castle and town. From Home of the Berkeley family for 850 years — Berkeley Castle (berkeley-castle.com)

The lords of Berkeley were important men, and while they often travelled by barge using the now-gone Berkeley Pill (creek) which came right to the castle, they also needed to be able to get to and from by land. After all, in poor weather the estuary wasn’t always passable So they’d have made certain they had a useable land route of some sort. They had to, because it wasn’t always convenient to strike across open countryside, especially if the bad weather had also result in floods. Necessary roads could be raised above such hazards, of course, but could be doesn’t mean they were.

In a book written by David Tandy, called Berkeley: A Town in the Marshes, the opening page describes the town as follows: “On a small hill in Gloucestershire, in an area known as the Berkeley Vale, not far from the banks of the river Severn, is the town of Berkeley…[This hill] is only 16 metres above sea level, and the base of the hill only 8 metres above sea level.” It goes on to mention how often waterways have overflowed the surrounding land, including the Severn itself. For many centuries the surrounding countryside was considered to be a marsh.

The castle is on the southern edge of the town of Berkeley, from where it is a short well-trodden distance (about one and a half miles) east to the even more well-trodden north-south Roman road from Gloucester to Bristol (today’s A38, superseded by the adjacent M5 motorway). It is shown as a Roman road (unnamed) on the page 19 map of A History of Bristol and Gloucestershire, by Smith and Ralph, but may simply have been a significant Saxon route. The truly Roman Fosse Way lies further east. Either way, the Gloucester to Bristol was a prominent road. On another map on page 24 of the same book, Berkeley itself is described as an “important late Saxon town”.

Berkeley Castle as such dates from the completion of the keep in the late 12th Century, and ever since, over 800 years, it has been owned and occupied by the same family, the Berkeleys. In the 14th century Thomas Lord Berkeley held up to four court leets a year and the town had been a borough since at least the reigns of Henry II/III. It would even have its own mint by the end of Edward III’s reign. Go to these comments to read about a coin discovered in a field near Berkeley. Alas, not minted in Berkeley because it predates Edward III.

So to believe Berkeley lacked made-up roads stretches credulity. Of course it depends upon what is meant by made-up—I assume Barber is referring to properly identifiable roads, because the 14th century predates tarmacadam and even cobbles only graced the more prominent streets in London. Medieval roads may not have been well kept but they were there in Berkeley when the young prince paid his visit in 1340. Hiring a guide out of Berkeley would surely not be required, let alone be essential.

Please note that from Berkeley the prince seems to have been aiming next for Andover. I haven’t gone so far as to investigate beyond the main road between Gloucester and Bristol, but it’s hard to imagine that a boy local to Berkeley would know the route all the way to Andover, but I suppose it’s not impossible. Presumably he would take them to a place from where they could continue their journey with the help of other guides as and when they were needed. I am aware that local guides were used regularly for journeys, but this specific mention of having to hire a boy in order to leave Berkeley seems a little unusual.

My only other guess would be that for some reason the prince chose to negotiate some of the very low, narrow and treacherous country tracks southeast of the town to join the main road further south, closer to Bristol. These would have been little more than farm tracks and to this day, while properly tarmacadamed they are still awkward and narrow. In a medieval winter (or wet summer) they’d be well nigh impassable because of the sucking claggy Severn clay mud, especially for wheeled vehicles.

Never ever underestimate Severn clay, it’s lethal, forming deep ruts like canyons. Ditches and streams always flood and it would have become too much for even horses to continue, so back in 1340 it would seem more sensible to me to always use the more well-travelled route, if possible. It may have been raised slightly and although it too would have ruts, some of them at least would be filled with stones. Berkeley certainly wasn’t completely cut off for half the year because of inclement weather! From my investigations, however, there was nothing untoward about the autumn weather of 1340.

Without knowing for certain which way the Berkeley boy might have taken them, my feeling is that even without him the prince would sensibly go east on leaving Berkeley Castle to join the busy main Gloucester-Bristol route. Now, I can’t imagine that a road of some sort didn’t lead from the town to the thoroughfare in the 14th century.

The countryside thereabouts is the low, wide, slightly undulating Vale of the Severn, which becomes known as Berkeley Vale in this vicinity, so surely not even the Anglo-Saxons (who didn’t seem to care much about straight lines when it came to our country lanes) would have made a dog’s breakfast of it by meandering all over the vale merely to go such an important short distance to and from Berkeley?

So, what’s all this about no roads and having to have a guide? I fear that curiosity is killing this poor old cat! Over to you Watson.

Leave a comment