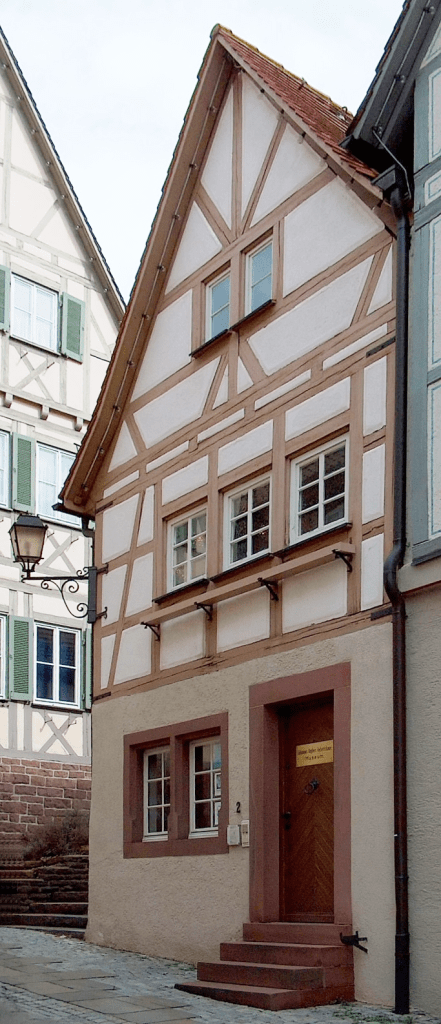

In 1577 Leonberg, Katharina Guldenmann took her small son “to a high place” for an advantageous view of a comet passing over what is now southwestern Germany. Three years later, the then eight-year-old boy’s father brought him out on a bitterly cold winter night to witness a lunar eclipse. Though in later years this boy enrolled at the University of Tübingen with the intention to be ordained at a local seminary, these two early experiences remained embedded in his being, and he ended up one of the most famous astronomers of his time.

We know this because Johannes Kepler to this day remains firmly embedded within the pantheon of international astronomers and physicists. Many of his own personal letters survive because they were worth keeping: as miniature treatises, they were chock full of fascinating details and breakthroughs, as well as his own impressions. He also kept meticulous autobiographical notes – one that even records the self-calculated time of his conception to the minute – in which we are made privy to pieces of his childhood, including the growth of the seeds earlier planted.

While there are some charming moments to witness or imagine – such as the young boy helping out in his grandfather’s restaurant and amazing diners with his prodigious mathematical skills – Kepler’s life was pocked by the hardship of illness and its aftereffects, personal misfortune, and the consequences of political power struggles. He also endured a skirmish with the law when legally defending his mother, whom he once described as “a luckless spirit,” against charges of witchcraft.

If all that weren’t enough, he had to navigate life – his included a great deal of travel for study, employment, and collaborations – under a power structure sown within a political agreement* hammered out nearly two decades before he was born, which dictated where he could live based on his religion. It was discriminatory and non-negotiable.

And yet he went on to become Kepler – the Kepler we talk about today, who achieved what, of course, we all know about, though many are not aware they know about: the three famous laws of planetary movement, and that which many of us didn’t. Kepler led the way into optics, the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of light; he was a mathematics professor and assistant to the eccentric astronomer Tycho Brahe, later analyzing Brahe’s notes and correctly assessing what they meant; he served as imperial mathematician to an emperor and advisor to a general; proved how logarithms work; contributed to the development of calculus; and as a novelist! And this isn’t even an exhaustive listing of everything Kepler achieved.

Of course, astronomy existed before Kepler – way before. The study goes back to before the ancient Greeks, but they were the first to explain what they saw in their skies. Dedicated fans of symmetry, they also favored a particular formation: a circle, believed to be the perfect shape. Therefore, what better than a circle to host the other amazing planets on their cycles around…the earth? Forward it moved, and so belief in a geocentric world did as well.

It wasn’t until over a millennium later that Nicolaus Copernicus expanded upon the heliocentric theory of an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician, who never did much more than speculate. Copernicus suffered s similar fate: the book he published, after decades of sitting on his information, was much too dense for a layman to read and scorned by those who understood it. This exalted company included Martin Luther.

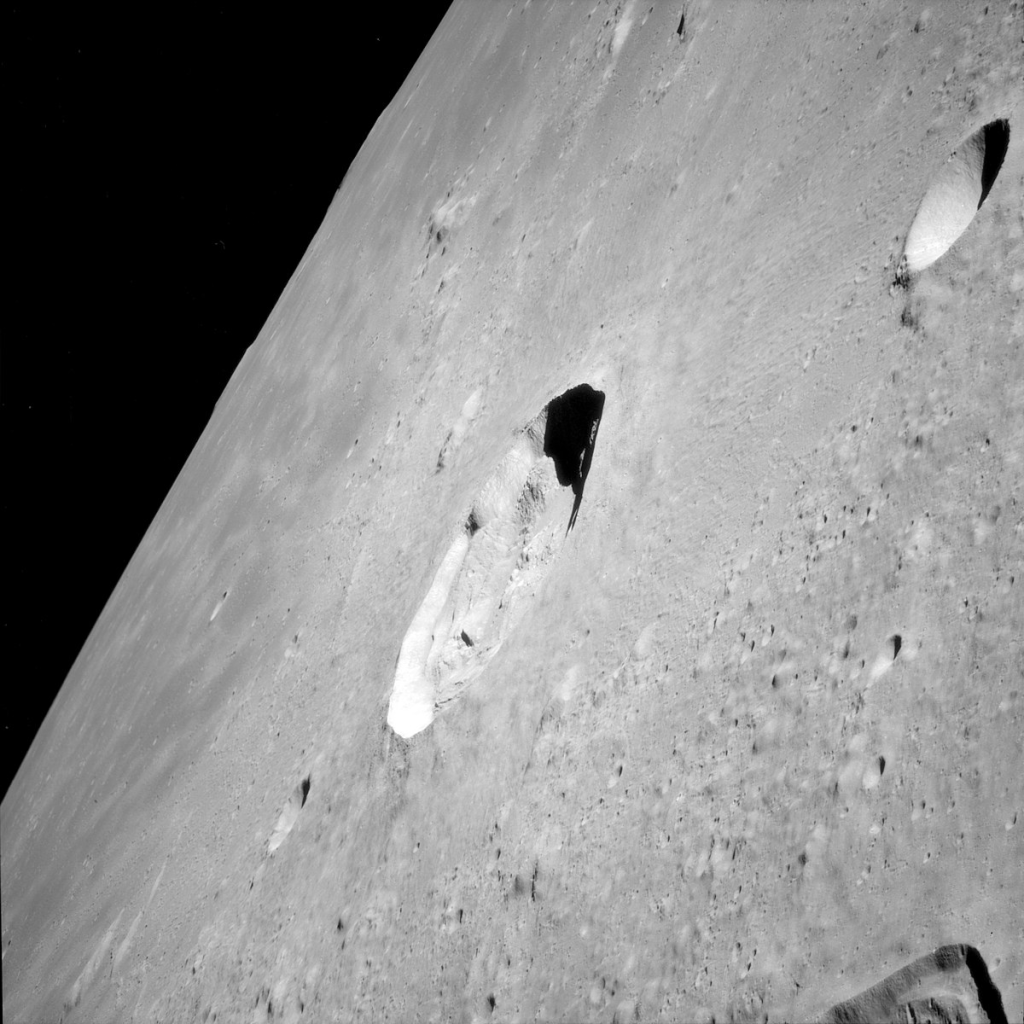

By the time Kepler got a hold of the theory, he had studied it (and much more!) extensively, exhaustively, and to his agreement with Copernicus’s assertion regarding the sun as center of the universe and not the earth, he added by expounding what was to become his first law of planetary movement: that the path planets traveled around the sun was elliptical and not circular. This led to the second, involving speed, and that the speed of these orbits was constantly changing. More specifically, a planet moves faster when close to the sun and slower when farther away, which goes a long way toward explaining why swimming weather is gone in twenty minutes and winter seems to last forever.

The third law involves the comparison of time and radius of planets to each other and is best summed up by someone far more skilled than I, at The Physics Classroom. And while we are here, I will also point readers to this video, Kepler’s Third Law, which provides a fascinating and fun look into Kepler’s laws as well as the physics behind it. The word physics scares a lot of people, especially us literary types who grew up being “bad at math” or not understanding science even a little. But if you give yourself permission to just watch and absorb what you can without beating yourself up over what you don’t immediately get, I won’t be surprised to find that at least some will go back for more.

I myself had similar beginnings to my admiration of Kepler as did author David Love:

“A long time ago, I found myself reading a lot about the history of astronomy. Ever since, I have been fascinated by two things. First of all, by Johannes Kepler, the extraordinary and brilliant sixteenth- and seventeenth-century astronomer whose life combined a high level of genius and originality with an appalling degree of personal tragedy and suffering. And second, by how and why it was that we have moved from the understandable but woefully inaccurate picture of the Universe that was accepted in Kepler’s time (and which Kepler began the long process of replacing) to the radically different insight that we have today.”

In my case, I came to Kepler via a bit of a rabbit hole. A math professor I used to chat with and who enabled the further development of my (clueless person’s) admiration of numbers talked to me about Bruno Giordano, which led me to the once-scandalous proposition of zero, to elementary school memories of Galileo, to a book I had found about Copernicus (The Book Nobody Read by Owen Gingerich)…I’ve lost the exact pathway, but suffice to say I stopped with Kepler, who fired up my brain, not only because of the same amazing start by Kepler to what we know today, but also because of his humanity and religiosity combined with science. He was a mathematician and a mystic. Maintaining a deep faith in God, Kepler also studied science for answers. In our modern and “progressive” world it seems the vast majority of people simply refuse to consider that science and religion aren’t polar opposites; they do work together. To Kepler, God was a scientist, and he wanted us to know the answers.

It also has not escaped me that Kepler, who had an extremely unhappy childhood and expressed some rather negative opinions about his mother, yet still credits her act of “sightseeing” as such a profound influence. Kepler, a religious man all his life, utilized medical knowledge at Katharina’s trial to destabilize claims of magic and superstition, ultimately saving her from the death penalty. And he saw her in himself: “I take from my mother my bodily constitution…the imagination of the mother imparts much upon the fetus.” L.S. Fauber, in Heaven on Earth, recounts that Kepler, who wrote of his father’s “inhumanity” toward his mother, “always maintained a certain sensitivity, if not sympathy, for what it meant to be a woman.” I believe I would agree with this.

Even in death, religious discrimination touched Kepler’s memory. As a Lutheran, he was not permitted burial in a Catholic cemetery, hence the earlier creation of a Lutheran burial ground outside of city walls. The cemetery, and Kepler’s grave itself, was later destroyed in the Thirty Years’ War.

*Augsburg Settlement

Works Consulted and Recommended/Listed for Further Exploration

Heaven on Earth: How Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler and Galileo Discovered the Modern World by L.S. Fauber

Kepler and the Universe: How One Man Revolutionized Astronomy by David Love

Kepler’s Philosophy and the New Astronomy by Rhonda Martens

“Kepler’s Three Laws” https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/circles/Lesson-4/Kepler-s-Three-Laws

“The History of Johannes Kepler” https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/the-history-of-johannes-kepler

“Kepler’s Third Law of Motion – Law of Periods (Astronomy)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbXVpdlmYZo

Leave a comment