Information about Blanche Bradestone (or Bradstone) is hard to find, despite the fact that she was recognised as ‘the King’s kinswoman’ by Richard II and became a Lady of the Garter in 1399.

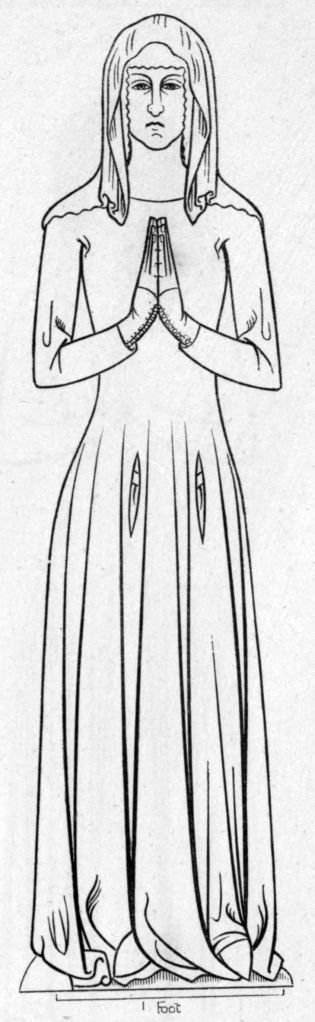

Her brass is to be found at Winterbourne, Gloucestershire, which appears to have been her principal manor. It is located in the church of St Michael the Archangel in that village and has been dated to 1370, which, if correct, makes it the oldest brass in the county. (Note the slits in her gown, so she can reach her purse, eating knife and other essentials, hidden below her dress but hanging from a girdle about her waist.)

The manor was held by the Bradestones from at least 1328, and it appears that, in later years at least, they were feudal tenants of Lord Berkeley, the capo del capi of southern Gloucestershire, it not the whole of it.

Blanche’s birth family is unknown, but by 1390 she was the wife of Sir Edmund Bradestone. Given the date of her brass, and the age of her son (see below) it is certain she had been his wife for some time, and it is quite possible she was born in the 1350s. The problem is, we lack the evidence to be absolutely sure.

On January 30th, 1393, “grant by special grace (was made) to Blanche Bradeston and her heirs of free warren in all the demesne lands of the manor of Winterbourne, co. Glos., and also of a weekly market in the town of Winterbourne, which is united to the said manor, and of two yearly fairs there, one on the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul, and the other on the feast of St. Luke the evangelist” (Cal. of Charter Rolls). On the Close Roll of 19 Richard II, Blanche is referred to by the name of her first husband. The chief butler of the port of Bristol is ordered to deliver “one tun of wine a year to Blanche Bradeston during her life, and the arrears since I March 8 Richard II, on which date the king granted her for life one tun of wine a year there, so that she should pay the merchant so much as the king should pay him.” (1)

Why Richard II was so generous is not apparent, but one possibility is that Blanche was indeed his ‘kinswoman’. She was not apparently so, but the lack of information about her birth family makes me wonder if it was Plantagenet – just on the wrong side of the blanket.

Her son, Thomas, presented the living of Winterbourne in 1405. To do this implies he was at least 21, which gives a birthdate of 1384. This again fits with Blanche being born in the 1350s or 1360s. Thomas may, of course, have been somewhat older than 21 in 1405.

The above grant was not Richard II’s only mark of favour. She also obtained pardons in 1394 and 1395 (which suggests both favour and ease of access) and another tun of wine from Bristol in 1399.

By 1392, Edmund Bradestone was dead, because in that year she married Sir Andrew Hake, a King’s knight who was later also a retainer of Thomas Despenser, Earl of Gloucester. Hake appears to have been a soldier of sorts, and an exiled Scot, but I have not found that he held any land in his own right, in Gloucestershire or elsewhere. To mark their marriage, Richard II bestowed an annuity of £40. This was increased by a further £60 in 1397 and there were a variety of other grants, either to the couple or to Blanche alone. The sun of Richard’s favour shone upon them. Even the £100, taken alone, was a decent income for a gentry couple. (2)

Blanche continues to be referred to as Lady Bradestone or Blanche Bradestone, or Blanche, Lady Bradestone, because her first husband was (presumably) of higher rank than her second. In such circumstances, medieval widows invariably kept their first title and the precedence that went with it.

In 1399, Blanche was appointed a Lady of the Garter. A rare honour, chiefly granted to close relatives of the King (although by no means all of them received it) or the widows of important knights, usually men who had achieved prominence in war. On the face of it, Blanche did not hit either qualification. It has been suggested that she was part of the entourage of the (very) young Queen Isabella. If this is so, it was yet another mark of high favour to someone who, on the face of it, was just an obscure gentlewoman from Gloucestershire.

Life was not all hay, though, for Hake and Blanche. Just before Easter, 1398, Winterbourne was attacked by lawless elements with the usual damage and looting. Given the context, this was almost certainly part of the power struggle in the county between Thomas, Lord Berkeley and Thomas Despenser, Earl of Gloucester. The latter, high in favour with Richard II, had lately begun to dominate the county, not least by placing his men in the top offices. As Berkeley had been running the show for years, he and his undoubtedly resented this change, even though he and Despenser were cousins. As Berkeley kept large numbers of armed men in his livery the struggle was by no means one-sided.

In the end, of course, Thomas Berkeley came out on top. The usurpation of Henry IV put him at an immediate advantage vis-a-vis his rivals and following the Epiphany Rising, both Andrew Hake and Thomas Despenser (3) were executed.

Blanche was not badly treated, and this again makes me suspect that she was some kind of Plantagenet, as Henry Bolingbroke was much more generous to women of his family than he was to other widows. She was granted Hake’s forfeited goods in January 1400 and an annuity of 200 marks in February. (2)

I have not, so far, been able to establish how long Blanche lived to enjoy this bounty.

(1) See https://www.frenchaymuseumarchives.co.uk/NewArchives.htm

In particular the article by Dr C B H Elliott, chapter on ‘The Manors’. This source gives much greater detail about the Bradestone family and its descent.

(2) See https://www.bgas.org.uk/tbgas_bg/v134/203-220-Wells-Furby.pdf. In particular, the footnotes that mention Blanche and Hake.

(3) The pedant in me forces me to state that Despenser was murdered by a mob, not lawfully executed. However, in practical terms, it amounts to the same thing. Despenser was rehabilitated in 1461, but no one bothered to rehabilitate Hake.

Leave a comment