I confess to having doubts about watching this two-part series on the Sky History channel because I envisaged CGI overkill with odious (but hopefully by then dead) parasites etc., and so I started viewing with the firm intention of stopping the moment it became too horribly wriggly and gory. No wriggles, but the gory parts almost got me a few times!

A decision to review the series had led me to record it, and I hesitated when in order to watch the first episode (about Charles II) I had to put in my pin number. Then came an on-screen warning of nudity and that it wasn’t for the faint-hearted. Good grief! Surely not an ailing royal todger? 😲 Pass the sal volatile this instant! Oh, and be warned too of some bad language, both in the documentaries and repeated in my review.

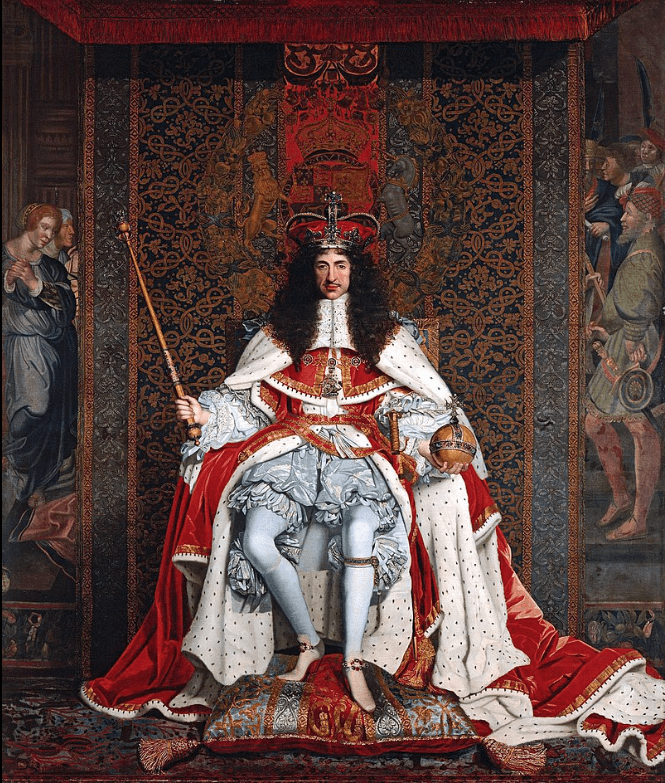

The presenter of the series is the very natural and watchable Dr. Alice Roberts (and see the illustration above). No airs and graces or silly theatricals, just a very sensible and knowledgeable presence.

NOW, IF YOU WANT TO BE SURPRISED AS YOU ACTUALLY WATCH THE PROGRAMMES, DON’T READ THIS REVIEW, BECAUSE THERE ARE MANY SPOILERS!

All the above said, here goes with Charles II….

Charles isn’t high on my list of go-to monarchs and my knowledge of his reign was mostly gleaned from the glut of historical novels set in his period that I devoured in my youth. Yes, yes, I confess that Forever Amber was one of them! 😊 Otherwise the Stuarts leave me as cold as the poor old Merry Monarch on the slab.

The king who’d brought fun and frivolity back to England after the misery of Cromwell & Co had apparently been hale and hearty on the eve of falling ill. He’d been suddenly hungry and called for an omelette, which was afterward thought believed may have given him food poisoning. That night severe stomach cramps beset him, as did awful diarrhoea and vomiting. But if it was food poisoning it was unpleasant but not serious, and certainly not terminal.

He suffered a convulsion the next morning and one of the court physicians, Dr Edmund King was sent for and immediately ordered the king be cupped of 16 oz of blood. This apparently did seem to bring the convulsion to an end, but it was a risky procedure for one physician on his own. If it had gone wrong, Dr King would get all the blame. But even though Charles was indeed calmed, his problems were now only just beginning because the then medical profession may have meant well, but it was usually disastrous. Fatal even.

It seems there’s still hot debate to this day about why and how Charles died. Seventeenth-century England was definitely not an ideal period for falling ill because of the very real risk of being helped on your way to the Hereafter by the ministrations of even the very top doctors in the land. As was stated later in the programme, the doctors of that time would be called quacks today.

So off we were taken to the modern examination room, where Dr. Brett Lockyer, Consultant Forensic Pathologist, wheels in the trolley with the king in a body bag. We are told in passing that Charles had been 6’ 2” tall….which placed him close to the tallest of our monarchs, but not the tallest. That accolade goes (I believe) to our very own Edward IV.

What might have seen Charles off to his Maker? His body had burn injuries on the forehead, incisions to the both sides of the throat and upper arms, three large circular bruises on his shoulders and a nasty ulcer on his right ankle. Good grief, what on earth had happened to him? Syphilis? Malaria? Apoplexy (we’d call it a stroke)? Poisoning? And oh dear, poisoning (the deliberate administering of poison, not food poisoning) was always high the list of suspects because it was so easy to use.

Charles’s licentious way of life may have helped cause the ankle ulcer. It seems such ulcers can indeed be a sign of syphilis. He had many mistresses, many of whom were shared around the court, which was ideal for the spread of STDs. But Dr Lockyer doesn’t think the king died of syphilis. The ankle ulcer may instead be gout-related. In other words, too much good living.

Dr Lockyer then examined the other marks etc. on the body. The incised wounds on the throat and upper arms probably indicated blood-letting. The circular bruises on the shoulders could result from cupping/bleeding. Both were signs of what doctors had done, not of disease. Even the injuries on the king’s forehead looked like chemical burns caused by a corrosive or blistering type of agent. Possibly another form of purging? If so, it was once again down to the physicians.

Back we’re taken to the time of Charles, whose condition was worsening, thus bringing the chief court physician Sir Charles Scarburgh, who on arrival suggested relieving pressure (and at the same time purging Charles’s toxins) with blistering agents and strong emetics. Bingo, the forehead damage is explained. Then the first physician, Dr King, suggested the addition of a plaster of spurge and Burgundy pitch. “Ah yes!” exclaimed Dr Scarburgh, “and make sure it’s rich in pigeon shit!” Eh? Pigeon poo?

In the examination room Dr Lockyer pointed to strange black staining on the base of the king’s foot. Seventeenth-century physicians believed that by administering a blistering agent to the head and then another purging agent to the foot, the ill humours would be drawn down from the head. Burgundy pitch is from the Norway spruce tree and burns the skin. Spurge is another agent to cause irritation. The saving grace was that pigeon faeces doesn’t smell! The court physicians smeared it on the underside of the royal foot to draw the ill humours and poisons that descended from the head and remove them from the body via the foot. (A long drawn-out process? 🙄 Sorry.)

Ah, the humours mentioned above must be explained to a modern audience, so over to The Royal Society of Medicine we go, to Jonathan Goddard who explained that fluids are one of the four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile, see here Humourism), which were believed to require constant balancing. Bleeding patients was believed to restore the balance; cupping also sucked out the poisons and evil humours. So back then doctors were always intent upon purging poisons and noxious humours from the body.

Then, at the Wellcome Collection we were shown a beautifully illustrated medical tome, the name of which escaped me. In Charles’s time the microscope was new, science was emerging and it was the start of the Age of Enlightenment, but they still followed the antiquated and frankly ridiculous requirements of humourism. With this in mind, physicians subjected poor old Charles to things like hellebore up the nostrils and the application of Spanish fly (very nasty stuff that also caused blistering). The advancement of medicine? Science? Hmmm.

In the examination room Dr Lockyer explained that the forehead wounds were probably the result of red-hot cauterising irons, which would have been applied to his head because he was fainting and losing consciousness. The belief was again that the poisons would be drawn away from his brain (and presumably down to the waiting exit provide by the pigeon poo). We didn’t actually see the grisly cauterising process but simply heard Charles’s screams from behind a closed door. If all this didn’t work, the final resort would probably be superstition. And Heaven alone knows what that might entail!

Dr Lockyer took some of Charles’s hair for toxicology, and the results revealed extremely high levels of mercury—ten times higher than average. Mercury could have been deposited on the hair externally or ingested. Either was possible. Dr Lockyer wasn’t sure if it played a significant part in his death. Charles was a great patron of science and established the Royal Society. Interested in astronomy and medicine, he was an amateur alchemist with his own laboratory. Had he poisoned himself accidentally while experimenting with chemicals?

So of all the external signs on the king’s body, only one—the ankle ulcer—was caused by disease. Everything else was the work of his doctors!

To find out what was the ultimate cause, Dr Lockyer had to delve inside the king. The post-mortem at the time concluded that he died of apoplexy (now known as a stroke). As he also had convulsive fits, Dr Lockyer removed the brain 🤢 but found nothing to indicate a stroke. Then came a Y-shaped incision on the king’s chest, and awful noises as the good doctor applied large clippers to the cut the ribs. 🤢 All organs (collectively termed the pluck) from the neck down to pelvis were removed as a whole and slapped down on a slab for examination. 🤢 There was fluid in the stomach, some of which was taken away for toxicology. It turned out to contain herbal extracts and alcohol, the latter probably from the various medicinal tinctures.

It was time for herbal remedies to be explained, so off we went to the Chelsea Physic Garden, which was there in Charles’s day and which his doctors would have known well. Today it boasts 5,000 species of medicinal plants, explained Nell Jones the Head Gardener. When told some of the things that Charles had been administered she confirmed they were all probably intended to induce diarrhoea and vomiting. “Medicinal and poisonous plants are pretty much the same thing, it’s just a case of dose and application.” (So we don’t want them to be prepared for us by anyone forgetful!)

Once again we returned to Charles’s time, where astonishingly, even after all this, the king actually seemed to improve. His physicians declared it to be “a triumph of modern medicine”. Then, just to be sure, they bled him of another 8 ozs! But soon he was in his final death throes. The convulsions returned, and among other things, extract of human skull was administered! 🤢 It sounded like witchcraft, or as Dr Alice Robert remarked, cannibalism!

Now there was a rapid decline in the illustrious patient. Too many cooks had finally spoiled the royal broth. The doctors were afraid of being blamed, and so they threw everything at the poor man, including Bezoar which is an almost mythical remedy consisting in Charles’s case of the ground-up stone sometimes found in a goat’s stomach. 🤢 It really is a last resort. So in Charles’s instance he had to take an awful mixture of ground-up human skull and vipers, hartshorn (which is exactly what it sounds like, see here Hartshorn), and last but not least, the goat’s innard.

On with the modern autopsy. Charles’s kidneys and liver should look more or less the same colour, but they don’t. The liver was OK, but the kidney we were shown was paler, rough and scarred, indicating chronic kidney disease. This was almost certainly due to the king’s high-protein diet. Before his death he’d been treated for “scalding urine”, and in the documentary is shown describing it as being like “pissing wasps”. This was uraemia, and could lead to convulsions. Having all this explained, we knew it was no surprise he died.

On Friday, 5th February 1685 Charles drew his final breath. Apparently his last words were “Don’t forget to wind the clocks.” This seemingly odd remark can be explained by going here.

Dr Lockyer told us that kidney disease and uraemia would be the causes of demise indicated on the death certificate he would issue. Charles had paid the price of his hedonistic lifestyle, and his final days were undoubtedly full of misery and pain.

To go back to the beginning of this review, the warning about nudity is a little puzzling. Certainly no shocking todgers, just the top half of the king’s body. Nothing you wouldn’t see on a beach….or many a high street in the summer. The worst bit for me was the removal of the internal organs and thumping them down wetly, as if in a shambles on market day. 🤢 Not nice viewing. Otherwise the programme was interesting, but definitely not for the squeamish.

Next I watched the second and so far the last episode in the series, this time about Elizabeth I….

The above likeness of Elizabeth I is called the Rainbow Portrait. It was shown in the programme and was apparently painted only a few years before her death, when she certainly did not look as young and virginal as this. Elizabeth had to keep up appearances and seem invulnerable to weakness and old age. In reality Good Queen Bess was a thin elderly woman in her sixties who was, they think, increasingly prey to doubt and depression. And she was frightened of having to decide upon an heir. Not a happy end.

Elizabeth had been on the throne since the age of 25 and died at 69. In that time she’d been a woman in what was most definitely a man’s world. She had to be strong and decisive, and she was. Oh, and just for the record, the programme credits the English Renaissance to her reign. (So take that, Henry VII! Not that even Elizabeth can really claim the Renaissance, which had started much earlier during the reign of the House of York. But that’s a by-the-by niggle….)

Once again there was an on-screen warning of nudity and reminder that it wasn’t for the faint-hearted. When she actually passed there not been a post-mortem because she herself had forbidden it. This of course, encouraged rumours, including (but not mentioned in the programme) that she wasn’t a woman at all, but a man! This rumour also explained why she hadn’t married or had children.

Enter again Dr Brett Lockyer, consultant forensic pathologist. We were shown Elizabeth’s upper body , with a glimpse of her breasts, which are subsequently concealed. This was the only instance of what I would term nudity, but if you’re sensitive to such things, you’ve been warned.

Dr Lockyer studied the body on the slab and saw hair loss, emaciation, terrible teeth, a swelling on the jaw and a very puffy, infected ring finger on her left hand. There were smallpox scars on her right clavicle, but they were very old, so smallpox was definitely not the cause of death.

He also noted the remains of white material on the face and identified it as the white lead face cosmetic that was fashionable in the queen’s time. White lead is a toxic metal and might well have caused the loss of hair and teeth. Had she perhaps suffered from chronic lead poisoning?

Her teeth were truly terrible, black, purple and green and damaged by caries, abscesses and gingivitis. (Her agony doesn’t bear thinking about.) We were taken back to her time and she was shown rubbing her teeth and gums with sugar paste to help with the pain. It seems sugar was a status symbol that was illicit, as is cocaine today. Whether it helped with pain, I don’t know. Teeth problems can also cause blood-poisoning, and there was a sinister bump on her jawline which Dr Lockyer identified as suppurative parotitis. A few jabs of his scalpel produced a lot of pus. 🤢 Suppurative parotitis is an infection of the salivary glands and causes a great deal of pain, and Dr Lockyer described it as “effectively an end of life condition”. It meant her body was slowing down and indeed closing down.

We were taken back to Elizabeth’s time again, when she was feeling awful and Sir Robert Cecil (always feathering his own nest, the narrative informs us) arrived with the day’s court papers. The queen’s lady-in-waiting tells him Elizabeth had consulted John Dee, who created her horoscope and advised her to move to Richmond because the move was in the stars and would be better for her “sickly old age”. (I can imagine Elizabeth’s reaction to the latter three words. Lead and balloon come to mind.)

The queen’s swollen left hand was the next to be subjected to Dr Lockyer’s eagle eye. There was a nasty infected wound on the ring finger with more pus. 🤢 because sepsis had set in. Today sepsis kills more people than many other illnesses together and in Elizabeth’s case was a sign that her heart wasn’t working as it should. The ring had been sawn off, thus creating the wound. Elizabeth had been greatly distressed because it was her coronation ring and therefore the symbol of her monarchy. To her it’s a dire ill omen that her end is approaching. Incidentally, she is not wearing the ring in the Rainbow Portrait above.

Now, be warned, it’s into the body we go. Another Y-shared incision, bones cut, as with Charles II. Finding fluid in the chest cavity, Dr Lockyer ladled it out for toxicology.🤢 The fluid indicated heart failure and explained the swollen left hand. Elizabeth had been shown in one scene describing a pain in her chest and her heart beating slow and heavy for days. “And a chain of iron about my neck.”

Next the pluck was again removed in one and slapped on to the slab. 🤢 We had detailed views of the cutting up of her lungs. 🤢 Lots of pus, indicating bronchopneumonia. Her heart was enlarged because the left ventricle wasn’t pumping correctly, and she would have had a fever.

What was known then as melancholia was considered another contributary cause of her death. She was very low and sad in the last weeks of her life, perhaps caused by religious conscience and starving herself. So we were whisked off to the Bethlem Museum of the Mind. There Dr Mary Ann Lund of the University of Leicester told us that melancholia, known also as black bile, was one of the four humours mentioned in the Charles II details above. Of the four humours—blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile—the black bile was hidden.

Comparing modern knowledge of depression, and the related physical signs it can cause, it seems obvious that Elizabeth’s final physical decline (during which she was emaciated, had lead poisoning, hair loss, infected parotid glands and tooth loss) was exacerbated by added symptoms due to depression. Did she lose the will to live? Being the eternal young Virgin Queen wasn’t possible. She was confronted by the knowledge that even she had to die.

We are taken to Elizabeth’s death bed. Still to name her heir, she lay silently as the final minutes ticked away. She was read a list of possible heirs, and supposedly nodded at the name of James VI of Scotland. It wasn’t verbal consent. Perhaps it was too much to finally say she’d hand the crown to the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, whose execution she’d ordered years before. Then, in early hours of 24th March 1603, she died.

Dr Lockyer gave his decision that the crucial primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and blood poisoning. He said that the heart would have been able to function until it was required to work harder. It couldn’t do that.

Thus passed the final Tudor….

Well, the programmes were well done, there’s no doubt of that, but for me they are definitely a one-time view only. Maybe if certain other monarchs had been on the slab I’d want to see them again, but not Charles II and Elizabeth I. For all that, it was very interesting and excellently presented and I’d have to recommend them. Just be ready for your squeams to be ished.

PS: You can read more about the series here, from which the first illustration above is taken.

Leave a comment