My lastest A Medieval Potpourri @sparkypus.com post.

Artist’s impression of a medieval wedding being solemnised. ‘Frieze of a Medieval Wedding’. Artist Thomas Stothard (1755-1835) Yale Centre for British Art.

I have, in my most recent meanderings, meandered quite a bit. Of late I’ve meandered from the Plague Pits of London 1665 to Gleaston Castle, rendezvous point for the 1487 Yorkist Rebels, to Medieval Doggies and from there to Love and Marriage in Late Medieval London (1). I came across this interesting little book while in a meandering search looking for another entirely different book and very pleased I am – I have learnt much from it. The subject of medieval marriages has been covered very well elsewhere but why I found this book a delight was because it details cases that were taken to the 15th century London Church Courts (2).This was usually in an attempt to have a marriage validated rather then dissolved – and in doing so opening up a window into the everyday lives of people of lower social levels and enabling their voices to be heard centuries later. The need for these cases was triggered by the ease in which a marriage could be made but sometimes the difficulty in getting them later legally recognised (should someone try to opt out for example) as well as, should the worse come to the worst, unmade. There was no obligation to have a witness present, leading to some cases where one of the spouses changed their minds at a latter date – perhaps in the heat of the moment one of the parties had got confused as to what was actually going on – as you do – or had even suffered a convenient bout of amnesia. The examples given in the book are interesting and in great detail and it’s a great shame that the outcomes, because they were noted elsewhere, are unknown.

So how did one get hitched in those times. All it took was for A to say to B ‘I take you B to be my wedded wife ‘and B to say to A ‘I take you A to be my wedded husband’ – known as present consent – and bingo! There was also future consent i.e. ‘I will take you…. ‘ which was immediately validated once consummation had taken place. In the case of the future consent marriage remaining unconsummated it could it be ended by mutual consent or if one of the partners made a present consent with someone else. This exchange of consent was known as a ‘contract’ and it was not required to have a priest in attendance although from the Church’s perception it was preferable there was.

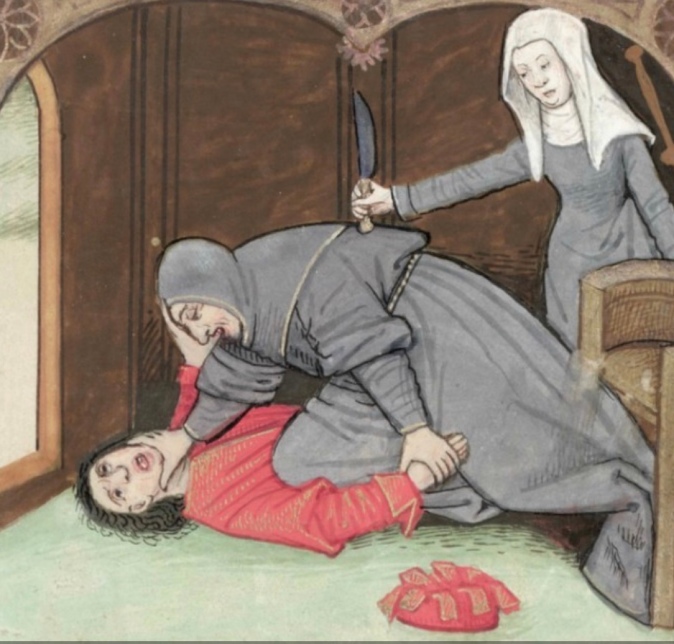

I do not know the origin of this illustration but it seems to me to scream a ‘future’ consent thing could be going on here..?

Neither were witnesses obligatory although of course, that too was desirable. Of course all this only applied to marriages where both parties were willing and not being coerced. I’ll return to this later. The next step was to make it generally known to family, friends, employers and neighbours etc., with perhaps a wedding feast to celebrate.

A 13th century wedding party celebration? 13th/14th century manuscript.

Finally, although not in all cases, after the banns were announced the wedding would be solemnised by an official church ceremony which could be performed either at the church door or in the nave of the church. The Church would take a dim view if this final step was not undertaken and it was considered sinful not to go through this procedure even though the couple would remain married. That was it basically.

Folk that were slow to solemnise the marriage in a church ceremony would be subtly persuaded by the local clergy…

Despite the almost casual ease of two people being able to enter into marriage by performing the ‘ceremony’ themselves in a domestic setting without the presence of a priest – and assuming there were no impediments – marriage was nevertheless viewed as one of the sacraments of the Catholic church thus in the event a dispute arising it would come under the jurisdiction of church law which was known as canon law. Divorce being rare these disputes were usually about validating the marriage rather than dissolving it. And this is where the ease of making a marriage and where it was not a necessary requirement to have witnesses could prove to be problematical in the event of one of the spouses later wanting out for whatever reason. It would then fall to the injured/deserted party to prove that the marriage had taken place. The book states ‘the issue at stake was almost always, whether or not consent had been properly exchanged, and a contract made. In other words, the party bring in the suit, usually wanted the court to validate the marriage, not to dissolve it’.

DIVORCE.

Marriage was then considered more or less indissoluble and divorce was practically unknown although it could be sought in extreme cases on the grounds of adultery ,heresy, coersion or cruelty. It should also be remembered that a medieval divorce was nothing like a modern divorce. The divorce that was known as a mensa et thoro (from table and bed) was more a legal separation which freed the spouses from their obligation to live and sleep together otherwise known as their conjugal debt. However the couple still remained married and thus unable to marry anyone else. Divorce a vincula (from the bond) was more of an annulment where the marriage had been invalid from the very beginning an example being: ‘The most common basis for a divorce a vincula was a prior contract or bigamy. X was already married to Y when he made a contract with Z, and thus X’s marriage to Z never existed as X could not be married to two women at the same time’.

To continue reading click here.

Leave a comment