I have been reading a very interesting article from the Journal of Medieval History by E. Amanda McVitty, called False knights and true men: contesting chivalric masculinity in English treason trials, 1388-1415. (Vol. 40, No. 4, 458–477)

There is an old saying that one man’s meat is another man’s poison, and by the very sensible reasoning in the above article it would seem that this is certainly true where treason is concerned. I mean, if a lord supports his king and the king is usurped, the lord can suddenly find himself charged as a traitor by the new king. This certainly happened when Richard III was hacked to death at Bosworth and replaced by Henry VII, who promptly strove to date his reign from the day before the battle, so that every one of Richard’s supporters could be declared traitor and their lands, property etc. etc. forfeit to the grasping usurper’s coffers. To my mind it was Henry and his supporters who were the traitors at Bosworth. Richard didn’t simply die in battle, he was murdered by treachery.

Anyway, the example of man-meat-poison that I will discuss here is that of Robert de Vere—Richard II—Henry IV, who were lord—king—usurper in that order. The situation was the same as in 1485 in that the usurper accused the lord of treachery…to himself, not Richard II. But how is it possible for a lord to carry out the orders of his friend and legitimate king, Richard II, and be accused of being a traitor because a usurper has taken the throne and killed Richard?

Robert de Vere was indeed a close friend of Richard’s. Grants and favours were heaped upon him and although he was Earl of Oxford by right, he advanced to Marquess (new rank invented for him) of Dublin and then Duke of Ireland. He was accused of trying to persuade Rich to make him King of Ireland! It didn’t happen, but even so he was raised in rank and importance above the king’s relatives, who, as you may guess, weren’t best pleased. There had always been whispers about Robert and Richard, but now those whispers intensified. The two men were said to be much more than mere friends. Nasty hints of sodomy abounded, placing Richard in the submissive role, which was an appalling weakness for a king. But even today there is no proof of anything wrong in Richard’s friendship with Robert de Vere. The worse than can be said is that Richard wasn’t very clever in the way he chose or dealt with his friends.

When the other magnates rose against Richard as the Lords Appellant, Richard responded by setting de Vere to raise an army on his behalf. This de Vere did, and the result was a humiliating rout at the battle of Radcot Bridge in December 1387. De Vere escaped, and those of his army left behind protested that they were acting on the king’s orders. This was true, and de Vere had Richard’s letters of proof on his person. Nevertheless, the Lords Appellent sat in judgement at the Merciless Parliament from February to June 1388. De Vere was accused of persuading Richard to advance him. Hint, hint again, because this rather placed Richard in another submissive—and therefore malleable—role. Robert was also attainted and sentenced to death in absentia and his titles and lands were forfeited. He would only return to England after death.

But was he a traitor, wicked and ambitious beyond all reason? Did he use his friendship to bend Richard to his will? Was he in the wrong? How could he be when he had Richard’s letters of instruction, ordering him to raise an army against the Appellants?

Setting aside the rumours of sexual impropriety, de Vere can be viewed as a loyal lord who served his king to the best of his (admittedly limited) ability. Militarily he wasn’t any great shakes, but even so he did what he could to obey his king.

Now I will quote from the above article:-

“….One of the charges against him in the Merciless Parliament was that at Radcot Bridge, ‘he rode with a great power and force of men-at-arms…and accroaching to himself royal power, caused the king’s banner to be displayed in his company.’89….”

Legally, raising the king’s banner against him was an act of treason.90 However, De Vere was in fact acting on the king’s orders and he was carrying letters from Richard to that effect.91 Challenged at Radcot Bridge by the Appellants’ forces, De Vere’s men claimed ‘they wished the lords [Appellant] ‘to understand that it is by the king’s orders that we have been riding in company with the duke of Ireland.’92 In the appeal of treason against De Vere, the Appellants were forced to explain their own violation of the king’s orders by claiming that the letters De Vere carried had been extracted by ‘wicked and treacherous prompting’, and that the treasonous favourite and his adherents had ‘caused the king to write to the said duke of Ireland’.93 Richard was positioned here as the passive pawn of men who had abused his trust to advance their own false causes while manoeuvring to destroy his ‘true’ nobles. However, elsewhere the same charge seems inadvertently to contradict this interpretation by giving the active role to the king, saying that the letters also promised ‘that the king would meet him [De Vere] with all his force, and that the king would there venture his royal person’.94 From the Appellants’ own account, De Vere appears to have been acting as a true knight by devoting his body to military service for his king, but this same performance of chivalric manhood had made him a traitor….

89 ‘Et issint chevocha ove grant poiar et force de gentz d’armes…en acrochant a lui roial poiar, fist espalier le baner du roi en sa compaignie’: ‘Appeal of Treason’, in PROME, vol. 7, Richard II 1385–1397, ed. Given-Wilson, 98, article 39.

90 Keen, ‘Treason Trials’, 96.

91 Knighton, 419–21. Saul, Richard II, 187, notes De Vere had orders under the king’s seal to raise troops in Cheshire.

92 ‘At illi respondentes dixerunt…“set jussa regis gracia tuicionis persone ducis Hibernie noverint nos secum pariter equitasse …”’: WC, 222–3.

93‘…malveis et traiterouses exitations’, ‘firent le roi escrier au dit duc d’Irland’: ‘Appeal of Treason’, in PROME, vol. 7, Richard II 1385–1397, ed. Given-Wilson, 97–8, article 38, my emphasis.

94‘…et qe le roi lui encontroit ovesqe tout soun poiar, et qe le roi ovesqe lui y metteroit en aventure soun corps roial’: ‘Appeal of Treason’, in PROME, vol. 7, Richard II 1385–1397, ed. Given-Wilson, 98, article 38….”

So, the Appellants wanted the meat and the poison! But they paid the price themselves, eventually, when Richard had his revenge. But it all went wrong for him, and one of those former Appellants, Henry of Bolingbroke, by then Duke of Lancaster, turned on him, usurped his throne and then had him killed. Thus a King Richard was killed by a Lancastrian cousin called Henry.

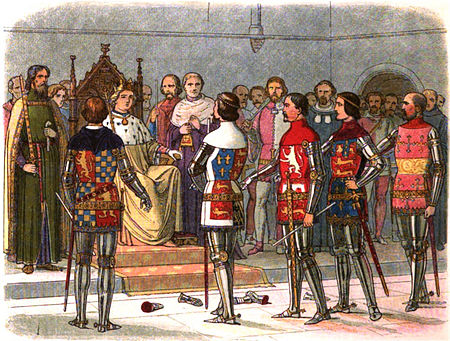

Which brings me back to Bosworth, and an illustration of the usurper Henry Tudor being “crowned” by a Stanley traitor. Both men come under the heading of “poison” to me!

Leave a comment